日本史33 Japanese history 33

化政文化(かせい・ぶんか)Kasei culture

山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)

『南総里見八犬伝(なんそう・さとみ・はっけんでん)Nansō Satomi Hakkenden』

九六式艦上戦闘機(きゅうろくしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)Type 96 Carrier-based Fighter

九六式艦上戦闘機(きゅうろくしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)Type 96 Carrier-based Fighter

零式艦上戦闘機(れいしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)The Type 0

carrier-based fighter(零戦(ぜろせん)Zero Fighter)

九六式艦上戦闘機(きゅうろくしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)Type 96 Carrier-based Fighterは、日本海軍Imperial Japanese Navyの艦上戦闘機Carrier-borne Fighterである。

The Type 96 carrier-based

fighter is a carrier-based fighter of the Japanese Navy.

海軍初The Navy's

firstの全金属All-metal単葉戦闘機Monoplane

Fighter。

The Navy's first

all-metal monoplane fighter.

アメリカ側のコードネームCode nameは“クロードClaude”。

The American code name is

"Claude".

後継機Successorは零式艦上戦闘機(れいしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)The Type 0 carrier-based fighter(零戦(ぜろせん)Zero Fighter)。

Its successor is the Type

0 carrier-based fighter.

九六式艦上戦闘機(きゅうろくしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)Type 96 Carrier-based Fighter

P-26ピーシューター Boeing P-26 Peashooter

カーチス・ホークIII Curtiss BF2C Goshawk

当時日中戦争Second Sino-Japanese War中であった中国Chinaに送られた機体は、空中戦Aerial warfareで当時のP-26ピーシューターBoeing P-26 Peashooterやカーチス・ホークIII Curtiss BF2C

Goshawkなど中国軍戦闘機Chinese military fightersを圧倒した。

The aircraft sent to

China, which was engaged in the Sino-Japanese War at the time, overwhelmed

Chinese military fighters such as the P-26 Peashooter and Curtiss Hawk III in

dogfights.

九六式艦上戦闘機(きゅうろくしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)Type 96 Carrier-based Fighter

零式艦上戦闘機(れいしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)The Type 0

carrier-based fighter(零戦(ぜろせん)Zero Fighter)

空母鳳翔(ほうしょう) Aircraft

carrier Hosho

空母龍驤(りゅうじょう) Aircraft

carrier Ryujo

空母祥鳳(しょうほう) Aircraft

carrier Shoho

空母瑞鳳(ずいほう) Aircraft carrier Zuiho

空母大鷹(たいよう) Aircraft carrier Taiyo

太平洋戦争Pacific War序盤1942年(昭和17年)までは、後継機successor

aircraftである零式艦上戦闘機(れいしき・かんじょう・せんとうき)The Type 0 carrier-based fighter(零戦(ぜろせん)Zero Fighter)の配備が間に合わず、鳳翔(ほうしょう)Hosho・龍驤(りゅうじょう)Ryujo・祥鳳(しょうほう)Shoho・瑞鳳(ずいほう)Zuiho・大鷹(たいよう)Taiyoの各空母Aircraft Carrier、および内南洋(うちなんよう)South Seas Mandateや後方の基地航空隊Land-based air unitに配備されていた。

Until 1942, at the

beginning of the Pacific War, the successor aircraft, the Type 0 carrier-based

fighter, was not deployed in time, and the Hosho, Ryujo, Shoho, and Zuiho ( It

was deployed on the aircraft carriers Zuiho and Taiyo, as well as base air units

in the Inner South Seas and rear bases.

1942年(昭和17年)末には概ね第一線から退き、以降は練習機training aircraftとして終戦the end of the warまで運用された。

At the end of 1942, it

was largely retired from the front lines, and was used as a training aircraft

until the end of the war.

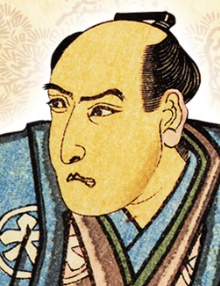

『市川鰕蔵(いちかわ・えびぞう)Ichikawa Ebizō』

東洲斎写楽(とうしゅうさい・しゃらく)Tōshūsai Sharaku

第9章 Chapter 9

幕藩体制の動揺

Unrest in the Shogunate

system

第3節 Section 3

化政文化(かせい・ぶんか)Kasei culture

文化文政文化(ぶんか・ぶんせい・ぶんか)Bunka Bunsei culture(1804年~1830年)

草双紙(くさ・ぞうし)Kusazōshi

小説(しょうせつ)Novel

17世紀後半頃に、児童向きの絵物語(え・ものがたり)illustrated storiesとして発生した草双紙(くさ・ぞうし)Kusazōshiは、やがて成人向きの挿絵文学(さしえ・ぶんがく)illustrated literatureとなり、内容によって表紙(ひょうし)Book coverを塗り分け、赤本(あか・ほん)red books・青本(あお・ぼん)blue books・黒本(くろ・ぼん)black books・黄表紙(き・びょうし)yellow booksなどと言われた。

Kusazoshi, which originated

as illustrated stories for children in the late 17th century, eventually became

illustrated literature for adults, and the covers were colored differently

depending on the content, and were divided into red books, blue books, black

books, and yellow books.) etc.

黄表紙(き・びょうし)Kibyōshi

特に18世紀後半に見られる黄表紙(き・びょうし)Kibyōshiは、今までの子供向きの本から発展して成人向きの内容を持ち、当時の風俗customs・政治politicsなど、江戸市中の話題current topics in Edoを直ちに取り上げるfeatured current events時事性をもった小説(しょうせつ)Novelである。

In particular, the

yellow-covered books that appeared in the latter half of the 18th century

evolved from books aimed at children up until now to have content for adults,

and featured current events such as the customs and politics of the time, as

well as current topics in Edo. It is a novel with sexuality.

『金々先生栄花夢(きんきん・せんせい・えいが・の・ゆめ)Kinkin Sensei Eiga no Yume』 恋川春町(こいかわ・はるまち)Koikawa Harumachi(1744~1789) 黄表紙(き・びょうし)Kibyōshi

恋川春町(こいかわ・はるまち)Koikawa Harumachi(1744~1789)

『金々先生栄花夢(きんきん・せんせい・えいが・の・ゆめ)Kinkin Sensei Eiga no Yume』

『金々先生栄花夢(きんきん・せんせい・えいが・の・ゆめ)Kinkin Sensei Eiga no Yume』の恋川春町(こいかわ・はるまち)Koikawa Harumachi(1744~1789)や山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)らが代表的な作者representative authorであるが、寛政の改革(かんせい・の・かいかく)the Kansei reformsで弾圧reformsされた。

Koikawa Harumachi

(1744-1789) and Santokyoden (1761-1816) from "Kinkin Sensei Eiga no

Yume" Although he is a representative author, he was suppressed during the

Kansei reforms.

山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)

洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebonは、江戸Edoの遊里(ゆうり)leisure villageを舞台に、日常会話everyday

conversationsを主体とし、町人の遊興the townspeople's pastimesや通(つう)の姿a man

of the worldを、滑稽・軽妙にin a humorous and lighthearted manner描いた。

Set in a leisure village

in Edo, it depicts the townspeople's pastimes and street life in a humorous and lighthearted manner, with the main

focus being everyday conversations.

洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebon

『通言総籬(つうげん・そうまがき)Tsugen Somagaki』

山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)

洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebon

『仕懸文庫(しかけ・ぶんこ)Shikake Bunko』

山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)

洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebonは、田沼時代the Tanuma periodに全盛期を迎え、山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōdenの『通言総籬(つうげん・そうまがき)Tsugen Somagaki』・『仕懸文庫(しかけ・ぶんこ)Shikake Bunko』などがあるが、彼は寛政の改革(かんせい・の・かいかく)Kansei Reformsで風俗を乱したdisturbing public customsかどで手鎖50日間の処罰sentenced to

50 days in hand chainsを受けた。

He reached his heyday

during the Tanuma period, and his writings include Santo Kyoden's Tsugen

Somagaki and Shikake Bunko. He was sentenced to 50 days in hand chains for

disturbing public customs during reforms.

それ以来、洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebonは衰退し、このなかから滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibonと人情本(にんじょう・ぼん)Ninjōbonが分かれた。

Since then, pun books have

declined, and these books have been divided into comic books and ninjobon

books.

滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibonは、洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebonが衰退したあと、その滑稽味humorous

tasteを受け継いで、庶民の生活the lives of common peopleを写実的に描写realistically portrayedした。

After the decline of pun

books, they inherited their humorous taste and realistically portrayed the

lives of common people.

十返舎一九(じっぺんしゃ・いっく)Jippensha Ikku(1765~1831)

滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibon

『東海道中膝栗毛(とうかい・どうちゅう・ひざくりげ)Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige』

十返舎一九(じっぺんしゃ・いっく)Jippensha Ikku(1765~1831)

式亭三馬(しきてい・さんば)Shikitei Sanba(1776~1822)

代表作に十返舎一九(じっぺんしゃ・いっく)Jippensha Ikku(1765~1831)の『東海道中膝栗毛(とうかい・どうちゅう・ひざくりげ)Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige』、式亭三馬(しきてい・さんば)Shikitei Sanba(1776~1822)の『浮世風呂(うきよ・ぶろ)Ukiyoburo』・『浮世床(うきよ・どこ)Ukiyodoko』がある。

Representative works

include Ichiku Jippensha's (1765-1831) Tokai Dochu Hizakurige and Shikitei

Sanba (1776-1822). There are ``Ukiyoburo'' and ``Ukiyodoko''.

滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibon 『浮世風呂(うきよ・ぶろ)Ukiyoburo』

江戸Edoの湯屋bathhouseの朝湯morning

bath・女湯women's bath・男湯men's bathに立ち代りは入って来る客customersの様子appearance・会話conversationsを写実的に描写realistically depictsした。

Tachishiro realistically

depicts the appearance and conversations of customers entering the morning

bath, women's bath, and men's bath of an Edo bathhouse.

滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibon 『浮世床(うきよ・どこ)Ukiyodoko』

滑稽本(こっけい・ぼん)Kokkeibon 『浮世床(うきよ・どこ)Ukiyodoko』

床屋(理髪屋)barber shopに集まる隠居retirees・儒者Confucians・商人merchants・芸者geishasなど多種の人a variety of peopleのとりとめないrambling、しかし洗練されたsophisticated会話conversationsを写実的に描いたrealistically depicts。

It realistically depicts

the rambling but sophisticated conversations of a variety of people, including

retirees, Confucians, merchants, and geishas, who gather at a barber shop.

為永春水(ためなが・しゅんすい)Tamenaga Shunsui(1790~1843)

人情本(にんじょう・ぼん)Ninjōbonは、洒落本(しゃれ・ぼん)Sharebonから滑稽味を取り去ったものwith its humor removedで、江戸市民Edo citizensの退廃的な恋愛・好色the decadent love and amorous natureを中心とした人情the human

emotionsを主題としている。

It is a pun-style book

with its humor removed, and its theme is the human emotions centered on the

decadent love and amorous nature of Edo citizens.

『春色梅児誉美(しゅんしょく・うめごよみ)Shunshoku Umegoyomi』

人情本(にんじょう・ぼん)Ninjōbon

為永春水(ためなが・しゅんすい)Tamenaga Shunsui(1790~1843)

代表作representative

workに為永春水(ためなが・しゅんすい)Tamenaga Shunsui(1790~1843)の『春色梅児誉美(しゅんしょく・うめごよみ)Shunshoku Umegoyomi』があるが、彼は天保の改革(てんぽう・の・かいかく)Tenpō Reformsの風俗粛清the purge of customsにふれて処罰punishedされた。

His representative work is ``Shunshoku Umegoyomi'' by Shunsui Tamenaga (1790-1843), who was punished for touching upon the purge of customs during the Tenpo Reforms.

上田秋成(うえだ・あきなり)Ueda Akinari(1734~1809)

『雨月物語(うげつ・ものがたり)Ugetsu Monogatari』

上田秋成(うえだ・あきなり)Ueda Akinari(1734~1809)

『春雨物語(はるさめ・ものがたり)Harusame Monogatari』

上田秋成(うえだ・あきなり)Ueda Akinari(1734~1809)

読本(よみほん)Yomihonは、勧善懲悪主義(かんぜん・ちょうあく・しゅぎ)the principle of promoting good and punishing evilを主軸にした通俗文学a type

of popular literatureで、歴史上の人物や事件historical figures and incidents、さらには中国文学Chinese

literatureからの翻案をもとに、説話や筋the stories and plotsに趣向をこらしている。

Yomihon (read books) is a

type of popular literature that focuses on the principle of promoting good and

punishing evil, and it is based on historical figures and incidents, as well as

adaptations from Chinese literature, and adds flavor to the stories and plots.

雄大な構想の反面、儒教・仏教思想Confucian and Buddhist thoughtに基づく教訓lessonsを伴っている。

While it is a grand concept,

it also contains lessons based on Confucian and Buddhist thought.

寛政以後、人情本(にんじょう・ぼん)Ninjōbonなどに対する取り締まりcrackdownsが強化されて衰退すると、代わって読本(よみほん)Yomihonの全盛期が到来した。

After

the Kansei period, crackdowns on books on humanity (Ninjobon) were strengthened

and the book declined, and in its place the heyday of Yomihon (Yomihon) arrived.

曲亭馬琴(きょくてい・ばきん)Kyokutei Bakin(滝沢馬琴(たきざわ・ばきん)Takizawa Bakin)(1767~1848)

『南総里見八犬伝(なんそう・さとみ・はっけんでん)Nansō Satomi Hakkenden』 曲亭馬琴(きょくてい・ばきん)Kyokutei Bakin(滝沢馬琴(たきざわ・ばきん)Takizawa Bakin)(1767~1848)

『椿説弓張月(ちんせつ・ゆみはりづき)Chinsetsu yumiharitzuki』

曲亭馬琴(きょくてい・ばきん)Kyokutei Bakin(滝沢馬琴(たきざわ・ばきん)Takizawa Bakin)(1767~1848)

すでに大坂Osakaの国学者a Japanese scholar上田秋成(うえだ・あきなり)Ueda Akinari(1734~1809)は、『雨月物語(うげつ・ものがたり)Ugetsu Monogatari』・『春雨物語(はるさめ・ものがたり)Harusame Monogatari』を著し、神秘幽玄の趣を示す怪異小説の地位the status of mysterious novelsを確立していたが、化政期に入って、山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōdenに師事studiedした江戸Edoの曲亭馬琴(きょくてい・ばきん)Kyokutei Bakin(滝沢馬琴(たきざわ・ばきん)Takizawa Bakin)(1767~1848)が、『南総里見八犬伝(なんそう・さとみ・はっけんでん)Nansō Satomi Hakkenden』・『椿説弓張月(ちんせつ・ゆみはりづき)Chinsetsu yumiharitzuki』など、300編をこえる作品を著し、読本(よみほん)Yomihonを大成した。

Akinari

Ueda (1734-1809), a Japanese scholar from Osaka, has already written ``Ugetsu

Monogatari'' and ``Harusame Monogatari,'' which have the status of mysterious

novels with a mysterious and profound flavor. However, during the Kasei period,

Kyokutei Bakin (Takizawa Bakin) (1767-1848) of Edo, who studied under Santo

Kyoden, established Nansō. He wrote over 300 works, including ``Satomi

Hakkenden'' and ``Chinsetsu Yumi Harizuki,'' and became a great reader.

その作品はいずれも構想雄大で、複雑な事件を整然と脚色し、人々に愛好されたが、勧善懲悪(かんぜん・ちょうあく)promoting good and punishing evilの形式主義formalismに偏り、文学としての清新さに欠けた。

All of his works were

grand in concept, dramatized complex incidents in an orderly manner, and were

loved by people, but they lacked novelty as literature as they were biased

toward formalism of promoting good and punishing evil.

柳亭種彦(りゅうてい・たねひこ)Ryūtei Tanehiko(1783~1842)

読本(よみほん)Yomihonなどの流行に伴って、19世紀初めから黄表紙(き・びょうし)Kibyōshiの長編化became longer in lengthが進められ、数冊の黄表紙(き・びょうし)Kibyōshiを綴じ合わせて合巻(ごうかん)Gōkanと呼ばれた。

With the popularity of

reading books (yomihon), yellow-covered books became longer in length from the

beginning of the 19th century, and several yellow-covered books were bound

together to form a combined volume. I was called.

『偐紫田舎源氏(にせ・むらさき・いなか・げんじ)Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji』

柳亭種彦(りゅうてい・たねひこ)Ryūtei Tanehiko(1783~1842)

柳亭種彦(りゅうてい・たねひこ)Ryūtei Tanehiko(1783~1842)の『偐紫田舎源氏(にせ・むらさき・いなか・げんじ)Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji』は好評を博したが、天保期に江戸城大奥the

Ooku of Edo Castleを風刺satirizedしたかどで、版木没収the print was confiscated・追放の処罰Punished by expulsionを受けた。

Nehiko Ryutei

(1783-1842)'s ``Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji'' was well received, but the print

was confiscated during the Tenpo period because it satirized the Ooku of Edo

Castle. -Punished by expulsion.

賀茂真淵(かもの・まぶち)Kamo no

Mabuchi(1697~1769)

田安宗武(たやす・むねたけ)Tayasu

Munetake

加藤千蔭(かとう・ちかげ)Katō Chikage

村田春海(むらた・はるみ)Murata Harumi

文芸(ぶんげい)Literature

和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)

和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)は沈滞を続けたが、わずかに国学者Japanese scholarsから歌人poetsが現れた。

Waka poetry continued to

decline, but a few poets emerged from Japanese scholars.

『万葉集(まんようしゅう)Man'yōshū』を愛好した賀茂真淵(かもの・まぶち)Kamo no Mabuchi(1697~1769)は、万葉調Man'yōshū styleを提唱し、その門人his studentsに田安宗武(たやす・むねたけ)Tayasu Munetake・加藤千蔭(かとう・ちかげ)Katō Chikage(歌集collection of poems『うけらが花Ukeraga Hana』)・村田春海(むらた・はるみ)Murata Harumiらがいた。

Kamo Mabuchi (1697-1769),

who loved the Manyoshu, advocated the Manyoshu style, and his students included

Tayasu Munetake and Kato Chikage. (Ukeraga Hana, a collection of poems) and

Harumi Murata.

小沢蘆庵(おざわ・ろあん)Ozawa Roan

香川景樹(かがわ・かげき)Kagawa Kageki(1768~1843)

また京都(きょうと)Kyotoの小沢蘆庵(おざわ・ろあん)Ozawa Roanは、自然なままの感情を平淡な言葉で表現することを主唱し、その門人his student香川景樹(かがわ・かげき)Kagawa Kageki(1768~1843)も『古今集(こきんしゅう)Kokinshū』に範を求めて、家集the family collection『桂園一枝(けいえん・いっし)Keien Isshi』をあみ、桂園派(けいえんは)the Keien schoolと呼ばれた。

Roan Ozawa of Kyoto

advocated expressing natural emotions in plain words, and his student Kagawa

Kageki (1768-1843) also wrote ``Kokin no Kokin.'' Searching for a model in the

``Keien-ha'' collection, they followed the family collection ``Keien Isshi''

and became known as the Keien-ha school.

良寛(りょうかん)Ryōkan(1758~1831)

そのほか、越後(えちご)Echigo Province(新潟県(にいがたけん)Niigata Prefecture)の僧monk良寛(りょうかん)Ryōkan(1758~1831)は、その生活感情the

emotions of lifeを平明な調べで歌った。

In addition, the Echigo

monk Ryokan (1758-1831) sang about the emotions of life in a plain melody.

橘曙覧(たちばなの・あけみ)Tachibana no Akemi

平賀元義(ひらが・もとよし)Hiraga

Motoyoshi

大隈言通(おおくま・ことみち)Ōkuma

Kotomichi

幕末the end of

the Edo periodには、越前(えちぜん)Echizen Province(福井県(ふくいけん)Fukui Prefecture)の国学者scholars of Japanese studies橘曙覧(たちばなの・あけみ)Tachibana no Akemiや平賀元義(ひらが・もとよし)Hiraga Motoyoshi・大隈言通(おおくま・ことみち)Ōkuma Kotomichiらが万葉調の歌poems in the Manyo styleを詠んだ。

At the end of the Edo

period, Echizen scholars of Japanese studies such as Akemi Tachibana, Motoyoshi

Hiraga, and Kotomichi Okuma wrote poems in the Manyo style.

松尾芭蕉(まつお・ばしょう)Matsuo Bashō(1644~1694)

俳諧(はいかい)Haikai

松尾芭蕉(まつお・ばしょう)Matsuo Bashō以後蕉門(しょうもん)Shomonは分散し、蕉風(しょうふう)(正風)Shofuの形式化・俗化が進み、次第に当初の高い精神を失って衰退した。

After Basho, Shomon was

dispersed, the Sho style became more formalized and vulgarized, and it gradually

lost its original high spirit and declined.

横井也有(よこい・やゆう)Yokoi Yayū(1702~1783)

与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Buson(1716~1783)

しかし、宝暦期に、横井也有(よこい・やゆう)Yokoi Yayū(1702~1783)は『鶉衣(うずら・ごろも)Uzuragoromo』を著して俳文に新分野を開き、天明期には、摂津の与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Buson(1716~1783)が松尾芭蕉(まつお・ばしょう)Matsuo Bashōへの復帰を唱えて俳諧を中興revitalized haikaiした。

However, during the

Horeki period, Yayu Yokoi (1702-1783) opened a new field of haiku by writing

Uzuragoromo, and during the Tenmei period, Yosama of Settsu. Yosa Buson

(1716-1783) advocated a return to Basho and revitalized haikai.

与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Buson(1716~1783)

与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Busonは、華麗描写に富む絵画的な句を詠んで天明調Tenmei-style

poemsと称され、『蕪村七部集(ぶそん・しちぶ・しゅう)Buson Seven Parts Collection』を残した。

Buson was known for his

Tenmei-style poems, which were rich in gorgeous depictions, and left behind the

``Buson Seven Parts Collection.''

小林一茶(こばやし・いっさ)Kobayashi

Issa(1763~1827)

化政期には信濃(しなの)Shinano Province(長野県(ながのけん)Nagano

Prefecture)の小林一茶(こばやし・いっさ)Kobayashi Issa(1763~1827)が、俗語・方言を自由に用い、弱者への温かい同情心を示す人間味豊かな句を残して異彩を放った。

During the Kasei period,

Issa Kobayashi (1763-1827) of Shinano distinguished himself by freely using

slang and dialect and leaving behind humane poems that expressed warm sympathy

for the weak. .

句集haiku

collectionに『おらが春Oragaharu』がある。

His haiku collection

includes ``Oragaharu.''

大田南畝(おおた・なんぽ)Ōta Nanpo(蜀山人(しょくさんじん)Shokusanjin)(1749~1823)

狂歌(きょうか)Kyōka

和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)の形式をかり、口語を用い、洒落・滑稽と即興を生命とし、当時の政治・世相・風俗を巧みにうがち、町人に喜ばれた。

Using the form of waka

poetry, using colloquial language, and relying on humor, humor, and improvisation,

his works skillfully conveyed the politics, social conditions, and customs of

the time, and were well received by the townspeople.

石川雅望(いしかわ・まさもち)Ishikawa

Masamochi(宿屋飯盛(やどやの・めしもり)Yadoya no Meshimori)(1753~1830)

朱楽管江(あけら・かんこう)Akera Kankō

狂歌師(きょうかし)Kyōka poetsに、もと旗本(はたもと)Hatamotoの大田南畝(おおた・なんぽ)Ōta Nanpo(蜀山人(しょくさんじん)Shokusanjin)(1749~1823)・国学者Japanese scholar石川雅望(いしかわ・まさもち)Ishikawa Masamochi(宿屋飯盛(やどやの・めしもり)Yadoya no Meshimori)(1753~1830)・朱楽管江(あけら・かんこう)Akera Kankōが知られた。

Kyoka poets include

former hatamoto Ota Nanpo (Shokusanjin) (1749-1823), Japanese scholar Masamochi

Ishikawa (Yadoyano Meshi) Mori)) (1753-1830) and Akera Kanko became known.

狂歌集(きょうかしゅう)Kyōka collectionsに『万載狂歌集(まんざい・きょうかしゅう)Manzai Kyokashu』・『故混馬鹿集(ここん・ばかしゅう)Kokon Bakashyu』などがある。

Kyoka collections include

``Manzai Kyokashu'' and ``Kokon Bakashyu''.

柄井川柳(からい・せんりゅう)Karai Senryū(1718~1790)

黒船来航(くろふね・らいこう)Kurofune

raikō(Arrival of the Black

Ships)

蒸気船(上喜撰(じょうきせん))、たった四杯で夜も眠れず Steamboat (Jokisen), I couldn't sleep at night after just four

drinks.

川柳(せんりゅう)Senryū

川柳(せんりゅう)Senryūは、俳句(はいく)haikuの形をとって政治や世相などを皮肉な眼でとらえ、滑稽・風刺と即興をもって表現するもので、江戸町人Edo townspeopleに歓迎された。

Senryu (senryu) takes the

form of haiku and takes an ironic view of politics and social conditions,

expressing them through humor, satire, and improvisation, and was welcomed by

Edo townspeople.

前句付(まえくづけ)Maekuzukeの点者(てんじゃ)Tenjaをしていた江戸Edo浅草Asakusaの町名主the

town head柄井川柳(からい・せんりゅう)Karai Senryū(1718~1790)から川柳(せんりゅう)Senryūの呼称がおこり、彼を中心に『俳風柳多留(はいふう・やなぎ・だる)Haifu Yanagi Daru』がつくられた。

The name Senryu (Senryu)

came from Karai Senryu (1718-1790), the town head of Asakusa, Edo, who was the

Tenja (Maekuzuke), and the name Senryu (Senryu) originated from him. ``Haifu

Yanagi Daru'' was created.

竹田出雲(たけだ・いずも)Takeda Izumo

『菅原伝授手習鑑(すがわら・でんじゅ・てならい・かがみ)Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami』

『義経千本桜(よしつね・せんぼん・ざくら)Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura』

『仮名手本忠臣蔵(かなでほん・ちゅうしんぐら)Kanadehon Chūshingura』

演劇(えんげき)Theatre

浄瑠璃(じょうるり)Jōruri

近松門左衛門(ちかまつ・もんざえもん)Chikamatsu

Monzaemon(1653~1724)の指導を受けた大坂Osakaの竹本座(たけもとざ)Takemoto-za二世the second

generation竹田出雲(たけだ・いずも)Takeda Izumoは浄瑠璃原作者the original author of joruriとしても活躍し、『菅原伝授手習鑑(すがわら・でんじゅ・てならい・かがみ)Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami』・『義経千本桜(よしつね・せんぼん・ざくら)Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura』・『仮名手本忠臣蔵(かなでほん・ちゅうしんぐら)Kanadehon Chūshingura』などの名作を残した。

Takeda Izumo, the second

generation of Osaka's Takemoto-za, who was trained by Chikamatsu Monzaemon

(1653-1724), was also active as the original author of joruri, and wrote the

book ``Sugawara Denju Handbook''. He left behind masterpieces such as

``Yoshitsune, Senbon, and Sakura'', ``Kanadehon Chushingura'', and ``Kanadehon

Chushingura''.

近松半二(ちかまつ・はんじ)Chikamatsu

Hanji(1725~1783)

『本朝廿四孝(ほんちょう・にじゅうしこう)Honcho Nijushiko』

『傾城阿波の鳴門(けいせい・あわの・なると)Keisei Awa no Naruto』

『妹背山婦女庭訓(いもせやま・おんな・ていきん)Imoseyama Onna Teikin』

その門人disciple近松半二(ちかまつ・はんじ)Chikamatsu

Hanji(1725~1783)も、『本朝廿四孝(ほんちょう・にじゅうしこう)Honcho Nijushiko』・『傾城阿波の鳴門(けいせい・あわの・なると)Keisei Awa no Naruto』・『妹背山婦女庭訓(いもせやま・おんな・ていきん)Imoseyama Onna Teikin』など優れた作品を著したが、浄瑠璃(じょうるり)Jōruriは、18世紀中頃の宝暦期を境に衰退に向かい、台本として見るべきものは少なくなった。

His disciple Chikamatsu Hanji (1725-1783) also wrote ``Honcho

Nijushiko'' and ``Keisei Awano Naruto''. ・Although he wrote excellent works such as ``Imoseyama Onna Teikin'',

Joruri began to decline after the Horeki period in the mid-18th century, and it

was no longer seen as a script. There are fewer things to do.

中村歌右衛門(なかむら・うたえもん)Nakamura

Utaemon

市川団十郎(いちかわ・だんじゅうろう)Ichikawa

Danjūrō

歌舞伎(かぶき)Kabuki

浄瑠璃(じょうるり)Jōruriの衰退に代わって、江戸を中心に歌舞伎(かぶき)Kabukiが著しい発展を示し、花道・回り舞台・せり上げなど、演劇効果を高める装置が完成した。

In place of the decline

of Joruri, Kabuki (Kabuki) showed remarkable development mainly in the Edo

period, and devices such as hanamichi, revolving stages, and elevated theaters were

perfected to enhance theatrical effects.

19世紀前半が歌舞伎(かぶき)Kabukiの全盛期で、江戸には中村座・市村座などの芝居小屋playhousesが盛況を呈し、中村歌右衛門(なかむら・うたえもん)Nakamura Utaemonや市川団十郎(いちかわ・だんじゅうろう)Ichikawa Danjūrōなどの名優Famous actorsが活躍した。

The first half of the

19th century was the heyday of Kabuki, and playhouses such as Nakamura-za and

Ichimura-za flourished in Edo, and theaters such as Nakamura Utaemon and

Ichikawa Danjuro flourished in Edo. Famous actors such as (Ro) played an active

role.

並木正三(なみき・しょうぞう)Namiki Shozo

並木五瓶(なみき・ごへい)Namiki Gohei

鶴屋南北(つるや・なんぼく)Tsuruya

Namboku(1755~1829)

脚本作家Script

writersとして並木正三(なみき・しょうぞう)Namiki Shozo・並木五瓶(なみき・ごへい)Namiki Gohei・鶴屋南北(つるや・なんぼく)Tsuruya Namboku(1755~1829)らが現れた。

Script writers such as

Shozo Namiki, Gohei Namiki, and Nanboku Tsuruya (1755-1829) appeared.

『東海道四谷怪談(とうかいどう・よつや・かいだん)Ghost Story of Yotsuya in Tokaido』

特に化政期の鶴屋南北(つるや・なんぼく)Tsuruya Nambokuは、退廃した世相を怪奇・残酷趣味を交えて描いた『東海道四谷怪談(とうかいどう・よつや・かいだん)Ghost Story of Yotsuya in Tokaido』をはじめ、その作品は百数十本の多きに及んでいる。

In particular, during the

Kasei period, Tsuruya Nanboku produced over 100 works, including ``Tokaido

Yotsuya Kaidan'', which depicts the decadent social conditions with a sense of

horror and cruelty. There are over a dozen books.

河竹黙阿弥(かわたけ・もくあみ)Kawatake Mokuami(1816~1893)

『三人吉三廓初買(さんにん・きちさ・くるわ・の・はつがい)Sannin Kichisa Kuruwa no Hatsugai』

その門人disciple河竹黙阿弥(かわたけ・もくあみ)Kawatake Mokuami(1816~1893)は、白浪物(しらなみ・もの)Shiranamimono(盗賊を主人公にした話)・世話物(せわ・もの)Sewamonoなど多方面に手腕をふるい、代表作に『三人吉三廓初買(さんにん・きちさ・くるわ・の・はつがい)Sannin Kichisa Kuruwa no Hatsugai』がある。

His disciple, Kawatake

Mokuami (1816-1893), was skilled in many fields, including Shiranamimono

(stories with thieves as the main characters) and Sewamono, and his

representative works include `` Sannin, Kissa, Kuruwano, and Hatugai.''

伊孚九(い・ふきゅう)Yi Fujiu

絵画(かいが)Painting

黄檗宗(おうばくしゅう)Ōbaku-shūの僧monksや、享保頃にたびたび渡来した中国人画家Chinese

painter伊孚九(い・ふきゅう)Yi Fujiuらによって南画(なんが)Nanga(南宗画(なんしゅうが)Nanshūga)が伝えられ、日本Japanでも学者scholars・文人literary figuresの間に流行spreadするようになり、文人画(ぶんじんが)Bunjingaと言われた。

Nanga (nanshuga) was

introduced by monks of the Obaku sect and the Chinese painter Ifukyu, who often

came to Japan around the Kyoho period, and it continued to spread in Japan as

well. It became popular among scholars and literary figures, and was called

Bunjinga (literati painting).

池大雅(いけの・たいが)Ike no Taiga(1723~1776)

池大雅(いけの・たいが)Ike no Taiga(1723~1776)

『十便十宜図(じゅうべん・じゅうぎ・ず)Juben Jugi zu』

天明期に入って、池大雅(いけの・たいが)Ike no Taiga(1723~1776)と与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Buson(1716~1783)によって日本文人画Japanese literati paintingsが大成され、池大雅(いけの・たいが)Ike no Taigaと与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Busonの合作『十便十宜図(じゅうべん・じゅうぎ・ず)Juben Jugi zu』などを残した。

In the Tenmei period,

Japanese literati paintings were perfected by Ike no Taiga (1723-1776) and Yosa

Buson (1716-1783). He left behind works such as ``Jubenjugizu.''

浦上玉堂(うらがみ・ぎょくどう)Uragami

Gyokudō(1745~1820)

田能村竹田(たのむら・ちくでん)Tanomura

Chikuden(1777~1835)

谷文晁(たに・ぶんちょう)Tani Bunchō(1763~1840)

谷文晁(たに・ぶんちょう)Tani Bunchō(1763~1840)

渡辺崋山(わたなべ・かざん)Watanabe Kazan(1793~1841)

『鷹見泉石像(たかみ・せんせき・ぞう)Takami Senseki zo』

そのほか浦上玉堂(うらがみ・ぎょくどう)Uragami Gyokudō(1745~1820)・田能村竹田(たのむら・ちくでん)Tanomura Chikuden(1777~1835)らや、ひろく諸派various schoolsを摂取adoptedした谷文晁(たに・ぶんちょう)Tani Bunchō(1763~1840)、その弟子discipleで『鷹見泉石像(たかみ・せんせき・ぞう)Takami Senseki zo』を残した渡辺崋山(わたなべ・かざん)Watanabe Kazan(1793~1841)などが有名である。

Others include Uragami

Gyokudo (1745-1820), Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835) Raya, and Tani Buncho (Tani

Buncho) who adopted various Hiroku schools. His disciple Watanabe Kazan

(1793-1841), who left behind the ``Takami Izumi Stone Statue,'' are famous.

沈南蘋(ちん・なんぴん)Shen Quan

円山応挙(まるやま・おうきょ)Maruyama Ōkyo(1733~1795)

『雪松図屏風(ゆきまつ・ず・びょうぶ)Yukimatsu zu byobu』

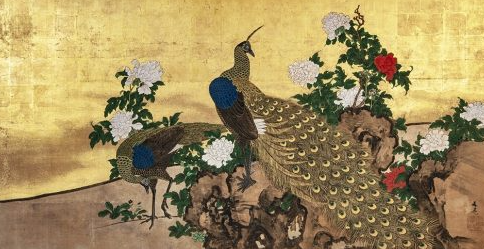

実証を尊重する時代風潮を反映して、写実的な写生画(しゃせいが)realistic sketch paintingsが発展した。

Reflecting the trend of

the times that valued demonstration, realistic sketch paintings developed.

京都(きょうと)Kyotoの円山応挙(まるやま・おうきょ)Maruyama Ōkyo(1733~1795)は、清(しん)の画家the Qing Dynasty painter沈南蘋(ちん・なんぴん)Shen Quanが伝えた写実法the realismと、西洋の透視的な写実主義Western perspective realismの影響influencedを受け、これに日本画Japanese paintingの装飾的表現法the decorative expression methodsを融合fusingさせて写生画(しゃせいが)realistic sketch paintingsを大成し、円山派(まるやまは)the Maruyama schoolと呼ばれ、『雪松図屏風(ゆきまつ・ず・びょうぶ)Yukimatsu zu byobu』などを残した。

Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795)

of Kyoto was influenced by the realism introduced by the Qing Dynasty painter

Shen Nanpin and Western perspective realism. He achieved sketch painting by

fusing the decorative expression methods of Japanese painting, and was known as

the Maruyama school, leaving behind works such as ``Yukimatsuzu''.

松村呉春(まつむら・ごしゅん)Matsumura

Goshun(月渓(げっけい)Gekkei)(1752~1811)

与謝蕪村(よさ・ぶそん)Yosa Buson・円山応挙(まるやま・おうきょ)Maruyama Ōkyoに学んだ円山派(まるやまは)the Maruyama schoolの松村呉春(まつむら・ごしゅん)Matsumura Goshun(月渓(げっけい)Gekkei)(1752~1811)は、文人画(ぶんじんが)Bunjingaと円山派(まるやまは)the Maruyama schoolの写生画(しゃせいが)realistic sketch paintingsを融合して四条派(しじょうは)the Shijō schoolを開いた。

Matsumura Goshun (Gekkei)

(1752-1811), a member of the Maruyama school who studied under Yosa Buson and

Maruyama Okyo, was a literati painter. (Bunjinga) and the Maruyama School's

sketch paintings to form the Shijo School.

酒井抱一(さかい・ほういつ)Sakai Hōitsu(1761~1828)

冷泉為恭(れいぜい・ためちか)Reizei

Tamechika

そのほかに琳派(りんぱ)Rinpa系統の酒井抱一(さかい・ほういつ)Sakai Hōitsu(1761~1828)、土佐派(とさは)the Tosa school系統の冷泉為恭(れいぜい・ためちか)Reizei Tamechikaらが有名であった。

Other well-known artists

included Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828), who belonged to the Rinpa school, and Reizei

Tamechika, who belonged to the Tosa school.

平賀源内(ひらが・げんない)Hiraga Gennai(1728~1779)

司馬江漢(しば・こうかん)Shiba Kōkan(1747~1818)

『西洋風俗図(せいよう・ふうぞく・ず)Western Customs』

鎖国(さこく)the national isolation後一時衰退した洋画(ようが)Western paintingsも、蘭学(らんがく)Dutch studiesの興隆the riseとともに再び盛んとなり、西洋画(せいようが)Western paintingsの遠近法などが学ばれた。

Western paintings, which

had declined for a while after the national isolation, became popular again

with the rise of Dutch studies, and people learned things like perspective in

Western paintings.

平賀源内(ひらが・げんない)Hiraga Gennai(1728~1779)や司馬江漢(しば・こうかん)Shiba Kōkan(1747~1818)が油絵画家oil paintersとして知られ、特に司馬江漢(しば・こうかん)Shiba Kōkanは、長崎Nagasakiで洋画(ようが)Western paintingsを研究researchedして『西洋画談(せいよう・がだん)Western Paintings』を著し、1783年(天明3年)、日本最初Japan's

firstの銅版画(どうばんが)copperplate engravings(エッチングetchings)に成功をおさめ、『西洋風俗図(せいよう・ふうぞく・ず)Western Customs』などを残した。

Hiraga Gennai (1728-1779)

and Shiba Kokan (1747-1818) are known as oil painters, and Shiba Kokan in

particular created Western paintings in Nagasaki. He researched and wrote

``Western Paintings'', and in 1783 (Tenmei 3), he succeeded in creating Japan's

first copperplate engravings (etchings), leaving behind works such as ``Western

Customs''.

亜欧堂田善(あおうどう・でんぜん)Aōdō Denzen(1748~1822)

『浅間山真景図屏風(あさまやま・しんけいず・びょうぶ)Mt. Asama True Scenery Byobu』

亜欧堂田善(あおうどう・でんぜん)Aōdō Denzen(1748~1822)

亜欧堂田善(あおうどう・でんぜん)Aōdō Denzen(1748~1822)も油絵oil

paintingや銅版画(どうばんが)copperplate engravings(エッチングetchings)を学び、洋風肉筆画Western-style hand-drawn painting『浅間山真景図屏風(あさまやま・しんけいず・びょうぶ)Mt. Asama True Scenery Byobu』を残した。

Aoudo Denzen (1748-1822)

also studied oil painting and copperplate engraving, and left behind a

Western-style hand-drawn painting called ``Mt. Asama True Scenery Byobu.''

鈴木春信(すずき・はるのぶ)Suzuki Harunobu(1725?~1770)

庶民the common

peopleに愛好された木版画woodblock printの浮世絵(うきよ・え)Ukiyo-eは、18世紀中頃から版画技術printmaking

technologyに改良が加えられ、田沼時代に、多色刷multicoloredの錦絵(にしき・え)Nishiki-eが鈴木春信(すずき・はるのぶ)Suzuki Harunobu(1725?~1770)によって発明された。

Ukiyo-e, a woodblock

print that was loved by the common people, was improved in printmaking

technology from the mid-18th century, and during the Tanuma period,

multicolored nishiki-e was produced by Harunobu Suzuki (1725). ?~1770).

こうして18世紀末から19世紀にかけて浮世絵(うきよ・え)Ukiyo-eは黄金時代golden ageを迎えた。

Thus, from the end of the

18th century to the 19th century, ukiyo-e entered a golden age.

鳥居清長(とりい・きよなが)Torii Kiyonaga(1752~1815)

喜多川歌麿(きたがわ・うたまろ)Kitagawa Utamaro

歌川豊国(うたがわ・とよくに)Utagawa

Toyokuni

東洲斎写楽(とうしゅうさい・しゃらく)Tōshūsai Sharaku

葛飾北斎(かつしか・ほくさい)Katsushika Hokusai(1760~1849)

安藤広重(あんどう・ひろしげ)Andō Hiroshige(歌川広重(うたがわ・ひろしげ)Utagawa Hiroshige)

美人画(びじん・が)Bijin-gaでは鈴木春信(すずき・はるのぶ)Suzuki Harunobu・鳥居清長(とりい・きよなが)Torii Kiyonaga(1752~1815)・喜多川歌麿(きたがわ・うたまろ)Kitagawa Utamaro、役者絵(やくしゃ・え)Yakusha-eでは歌川豊国(うたがわ・とよくに)Utagawa Toyokuni・東洲斎写楽(とうしゅうさい・しゃらく)Tōshūsai Sharaku、風景画(ふうけい・が)Landscape paintingでは葛飾北斎(かつしか・ほくさい)Katsushika Hokusai・安藤広重(あんどう・ひろしげ)Andō Hiroshige(歌川広重(うたがわ・ひろしげ)Utagawa Hiroshige)などが活躍した。

For

paintings of beautiful women, Suzuki Harunobu, Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815), and

Kitagawa Utamaro, and for actor paintings, Utagawa Toyokuni. ・Toshusai Sharaku, and landscape painters such

as Katsushika Hokusai and Ando Hiroshige (Utagawa Hiroshige) were active.

『婦女人相十品(ふじょ・にんそう・じゅっぴん)Fujo, Ninsou, and Juppin』

喜多川歌麿(きたがわ・うたまろ)Kitagawa Utamaro

高名美人六歌撰(こうめい・びじん・ろっかせん)

喜多川歌麿(きたがわ・うたまろ)Kitagawa Utamaro

喜多川歌麿(きたがわ・うたまろ)Kitagawa Utamaro(1753?~1806)は鳥居清長(とりい・きよなが)Torii Kiyonagaの影響を受け、女性の感情や姿体美を婉麗にして情味豊かな画趣で表現し、『婦女人相十品(ふじょ・にんそう・じゅっぴん)Fujo, Ninsou, and Juppin』・『高名美人六歌撰(こうめい・びじん・ろっかせん)』などを残し、美人画(びじん・が)Bijin-gaに縦横の才をふるった。

Kitagawa Utamaro

(1753?-1806) was influenced by Torii Kiyonaga, and expressed the emotions and

physical beauty of women in a graceful and sensitive style. , ``Fujo, Ninsou,

and Juppin'' and ``Six Poems of Famous Beauties'', and displayed a wide range

of talent in painting beautiful women.

『市川鰕蔵(いちかわ・えびぞう)Ichikawa Ebizō』

東洲斎写楽(とうしゅうさい・しゃらく)Tōshūsai Sharaku

東洲斎写楽(とうしゅうさい・しゃらく)(生没年不詳)は役者の舞台姿the stage appearances of actorsを見事にとらえ、『市川鰕蔵(いちかわ・えびぞう)Ichikawa Ebizō』などを残し、大首絵(おおくび・え)Ōkubi-eと言われる独特な表情をもつ独自の境地を開いた。

Toshusai Sharaku (date of

birth and death unknown) was a master at capturing the stage appearances of

actors, leaving works such as ``Ichikawa Ebizo'', and his unique facial

expressions known as Ōkubie. He has opened up a unique field of development.

葛飾北斎(かつしか・ほくさい)Katsushika Hokusai(1760~1849)

葛飾北斎(かつしか・ほくさい)Katsushika Hokusai(1760~1849)は、和漢洋諸派Japanese, Chinese, and Western schoolsの長所を摂取して、主観的な大胆な構図his bold, subjective compositionsと剛健な筆致robust

brushworkで風景画(ふうけい・が)Landscape paintingにおいて異彩を放った。

Katsushika Hokusai

(1760-1849) drew on the strengths of Japanese, Chinese, and Western schools and

distinguished himself in his landscape paintings with his bold, subjective

compositions and robust brushwork.

富嶽三十六景(ふがく・さんじゅうろっけい)Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji

葛飾北斎(かつしか・ほくさい)Katsushika Hokusai(1760~1849)

ヨーロッパ印象派the European

Impressionistsに影響を与えた『富嶽三十六景(ふがく・さんじゅうろっけい)Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji』は代表作である。

His representative work

is ``Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji,'' which influenced the European

Impressionists.

東海道五十三次(とうかいどう・ごじゅうさんつぎ)The 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō

安藤広重(あんどう・ひろしげ)Andō Hiroshige(歌川広重(うたがわ・ひろしげ)Utagawa Hiroshige)

名所江戸百景(めいしょ・えど・ひゃっけい)One Hundred

Famous Views of Edo

安藤広重(あんどう・ひろしげ)Andō Hiroshige(歌川広重(うたがわ・ひろしげ)Utagawa Hiroshige)

安藤広重(あんどう・ひろしげ)Andō Hiroshige(歌川広重(うたがわ・ひろしげ)Utagawa Hiroshige)(1797~1858)は、感情豊かな叙情性に富む作風a richly emotional and lyrical styleをもち、『東海道五十三次(とうかいどう・ごじゅうさんつぎ)The 53 Stations

of the Tōkaidō』・『名所江戸百景(めいしょ・えど・ひゃっけい)One Hundred Famous Views of Edo』などがある。

Hiroshige Ando (Hiroshige

Utagawa) (1797-1858) had a richly emotional and lyrical style, and his works

include ``53 Stations of the Tokaido'' and ``One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.''