日本史32 Japanese history 32

田沼時代と寛政の改革

Tanuma period and Kansei reforms

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobu(1758~1829)

九五式戦闘機(きゅうごしき・せんとうき)Type 95 Fighter

九五式戦闘機(きゅうごしき・せんとうき)Type 95

Fighter

九五式戦闘機(きゅうごしき・せんとうき)Type 95

Fighterは、日本陸軍Imperial Japanese Armyの戦闘機Fighter aircraft。

The Type 95 fighter is a

fighter aircraft of the Japanese Army.

連合軍Allied forcesのコードネームCode nameはペリーPerry。

The Allied code name is

Perry.

九五式戦闘機(きゅうごしき・せんとうき)Type 95

Fighter

開発・製造は川崎航空機(かわさき・こうくうき)Kawasaki Aircraft Industries。

Developed and

manufactured by Kawasaki Aircraft.

陸軍最後の複葉戦闘機Biplane fighterであり、主に日中戦争Second Sino-Japanese War(支那事変China Incident)初期early

stagesの主力戦闘機Main Fighter aircraftとして使用された。

It was the Army's last

biplane fighter, and was primarily used as the main fighter in the early days

of the Sino-Japanese War (China Incident).

ポリカールポフI-15戦闘機Polikarpov I-15

無類の運動性を利用して日中戦争Second Sino-Japanese Warの初期においては中国国民党軍Republic of China Armed Forcesのソ連製複葉戦闘機Soviet biplane fighterポリカールポフI-15戦闘機Polikarpov I-15などを圧倒する活躍をみせた。

Taking advantage of its

unparalleled maneuverability, it was able to overwhelm the Soviet-made biplane

Polikarpov I-15 fighter of the Chinese Kuomintang Army in the early stages of

the Sino-Japanese War.

ソ連製ポリカールポフI-16戦闘機Soviet

Polikarpov I-16 fighter

九七式戦闘機(きゅうななしき・せんとうき)Type 97

Fighter

九七式戦闘機(きゅうななしき・せんとうき)Type 97

Fighter

しかしノモンハン事件Nomonhan Incidentの頃になると、ソ連製ポリカールポフI-16戦闘機Soviet Polikarpov I-16 fighterのような単葉機Monoplane相手には劣勢となり、後継機Successorである九七式戦闘機(きゅうななしき・せんとうき)Type 97 Fighterと交替して第一線を退いた。

However, around the time

of the Nomonhan Incident, it was outnumbered by monoplanes such as the

Soviet-made Polikarpov I-16 fighter, and was replaced by its successor, the

Type 97 fighter, and retired from the front lines.

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)

第9章 Chapter

9

幕藩体制の動揺

Unrest in the Shogunate system

第2節 Section 2

田沼時代と寛政の改革

Tanuma period and Kansei reforms

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)

8代将軍the 8th shogun

徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa Ieshige(在職1745~1760)

9代将軍the 9th shogun

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimuneの子son

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)

Tanuma Okitsugu

1745年(延享2年)、徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)はその子son徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa

Ieshige(在職1745~1760)に将軍職the post of shogunを譲り、後見役his guardianとして政治took charge of politicsをみた。

In 1745, Tokugawa Yoshimune (in office 1716-1745) handed over the post of shogun to his son Tokugawa Ieshige (in office 1745-1760), who took charge of politics as his guardian.

大岡忠光(おおおか・ただみつ)Ooka Tadamitsu(1709~1760)

しかし徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimuneが死ぬthe deathと(1751年)、徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa Ieshigeの側用人(そばようにん)Sobayonin大岡忠光(おおおか・ただみつ)Ooka Tadamitsu(1709~1760)が重用important

positionされ、側用人政治(そばようにん・せいじ)Sobayonin Politicsが復活revivedして幕政腐敗the corruption of the shogunate governmentの端緒を開いたopened the beginning。

However, after the death

of Tokugawa Yoshimune (1751), Tadamitsu Ooka (1709-1760), a soba yonin of Tokugawa

Ieshige, was given an important position, and the side yonin politics became

important. was revived and opened the beginning of the corruption of the

shogunate government.

徳川家治(とくがわ・いえはる)Tokugawa

Ieharu(在職1760~1786)

10代将軍the 10th shogun

徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa

Ieshigeの子son

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)

徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa

Ieshigeの子son10代将軍the 10th shogun・徳川家治(とくがわ・いえはる)Tokugawa Ieharu(在職1760~1786)の時代the eraにも、側用人(そばようにん)Sobayonin田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)が重用an important postされ、老中(ろうじゅう)Rōjū(Elder)にまでなって実権powerを握った。

Even in the era of

Tokugawa Ieharu (1760-1786), the son of Tokugawa Ieshige, the 10th shogun,

Tanuma Okitsugu, a side servant. Tanuma Okitsugu (1719-1788) was given an

important post and held power until he became an old man.

田沼意行(たぬま・おきゆき)Tanuma Okiyuki

紀伊藩(きいはん)the Kii domainの足軽(あしがる)Ashigaruであった田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguの父father・田沼意行(たぬま・おきゆき)Tanuma Okiyukiは、徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimuneに従って江戸Edoに出て、600石の旗本(はたもと)Hatamotoとなった。

Motoyuki Tanuma, father

of Tanuma Okitsugu, who was an ashigaru of the Kii clan, followed Tokugawa

Yoshimune to Edo and became a hatamoto of 600 koku. became.

相良藩(さがら・はん)Sagara Domain

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsuguは徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa Ieshigeの小姓(こしょう)Koshōから側衆(そばしゅう)a side servantに、次いで1万石の大名(だいみょう)Daimyoに列せられ、徳川家治(とくがわ・いえはる)Tokugawa Ieharuの側用人(そばようにん)Sobayonin(1767年)・老中格(ろうじゅうかく)Rōjū

Kaku(1769年)を歴任して、1772年(安永1年)老中(ろうじゅう)Rōjū(Elder)に就任し、遠州(えんしゅう)Enshū(遠江(とおとうみ)Tōtōmi Province(静岡県(しずおかけん)Shizuoka Prefecture西部))相良藩(さがら・はん)Sagara Domain 5万3千石の大名(だいみょう)Daimyoとなった。

Tanuma Okitsugu was

promoted from a page to Ieshige Tokugawa to a side servant, then to a daimyo

with 10,000 koku, and then to a side servant to Ieharu Tokugawa. After successively

serving as Soba Yonin (1767) and Rochu Kaku (1769), he became Roju in 1772

(Yasun'ei 1), and became a feudal lord in Enshu Sagara with a wealth of 53,000

koku. became.

田沼意知(たぬま・おきとも)Tanuma

Okitomo(1749~1784)

その子son田沼意知(たぬま・おきとも)Tanuma

Okitomo(1749~1784)も若年寄(わかどしより)Wakadoshiyori(1783年)となり、父子father

and son相並んで政治にあたった。

His son Okitomo Tanuma

(1749-1784) also became Wakayori (1783), and both father and son were involved

in politics.

印旛沼干拓(いんばぬま・かんたく)Inbanuma Kantaku

大坂商人Osaka

merchant天王寺屋藤八郎(てんのうじや・とうはちろう)Tennojiya

Tohachiro・江戸商人Edo merchant長谷川新五郎(はせがわ・しんごろう)Hasegawa

Shingoroの出資で、下総(しもうさ)Shimousa Province(千葉県Chiba Prefecture北部)の印旛沼(いんばぬま)Lake Inba・手賀沼(てがぬま)Lake Tega(ともに利根川(とねがわ)Tone Riverの下流域)の干拓(かんたく)事業reclamation projectを計画した。

With investment from Osaka

merchant Tohachiro Tennojiya and Edo merchant Shingoro Hasegawa, a reclamation

project was planned for Lake Inbanuma and Lake Teganuma in Shimousa (both

located in the lower reaches of the Tone River).

しかし、印旛沼干拓(いんばぬま・かんたく)Inbanuma Kantakuは田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguの失脚fallで中絶abandonedし、手賀沼(てがぬま)Lake Tegaも1786年(天明6年)完成はしたが、同年の利根川大洪水(とねがわ・だいこうずい)the Tone River floodで破壊・流出destroyed and washed awayした。

However, Inbanuma Kantaku

was abandoned due to the fall of Tanuma Okitsugu, and Teganuma was completed in

1786 (Tenmei 6), but It was destroyed and washed away by the Tone River flood

in the same year.

工藤平助(くどう・へいすけ)Kudo Heisuke(1734~1800)

仙台藩(せんだい・はん)Sendai Domain医doctor工藤平助(くどう・へいすけ)Kudo Heisuke(1734~1800)は、1783年(天明3年)『赤蝦夷風説考(あかえぞ・ふうせつこう)Akaezo Fusetsuko』を著し、ロシア人の南下Russians' migration southwardとその密貿易smugglingを述べ、蝦夷地(えぞち)開拓developing Ezo landの必要necessityと日露貿易Japan-Russia tradeの得策the benefitsを主張した。

Heisuke Kudo (1734-1800),

a doctor of the Sendai clan, wrote "Akaezo Fusetsuko" in 1783 (Tenmei

3), which described Russians' migration southward and their smuggling. He

advocated the necessity of developing Ezo land and the benefits of Japan-Russia

trade.

当時、ロシア人Russiansのことを「赤蝦夷(あかえぞ)Akaezo」とか「赤人Akajin」と呼んでいた。

At that time, Russians

were called ``Akaezo'' or ``Akajin.''

最上徳内(もがみ・とくない)Mogami

Tokunai(1755~1836)

この意見を採用adopted this

opinionした田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguは、ロシアとの交易trade with Russiaを企て、出羽の最上徳内(もがみ・とくない)Mogami Tokunai(1755~1836)らを派遣dispatchedして蝦夷地(えぞち)Ezochi(北海道Hokkaido・千島Chishima・樺太Sakhalin)の調査を行わせた。

Tanuma Okitsugu, who

adopted this opinion, plotted trade with Russia and dispatched Mogami Tokunai

(1755-1836) and others from Dewa to Ezochi. Ezochi) (Hokkaido, Chishima, Sakhalin).

運上金(うんじょうきん)unjokin・冥加金(みょうがきん)myogakin

また、特定の商人certain merchantsに専売(せんばい)monopolyを許し、その代償として運上金(うんじょうきん)unjokin・冥加金(みょうがきん)myogakinを納めさせた。

In addition, he allowed

certain merchants to monopolize their products, and made them pay unjokin and

myogakin in return.

新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakuseki(1657年~1725年)

新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakusekiの定めた海舶互市新例(かいはく・ごし・しんれい)Kaihaku Goshi Shinrei(長崎新令(ながさき・しんれい)Nagasaki Shinrei・正徳新令(しょうとく・しんれい)Shōtoku Shinrei)を緩和relaxedし、貿易の促進promote tradeをはかった。

In order to promote trade,

he relaxed the new rules for the mutual trading of ships (Nagasaki new ordinance

and Shotoku new ordinance) established by Arai Hakuseki.

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)

積極的に商業資本を利用actively

utilizing commercial capitalしたことから、特権的な御用商人となった大商人の力the power of large merchantsは飛躍的に伸びたが、一方で商業高利貸資本commercial usury capitalの農村侵入が進み、農民farmersや在郷商人local merchantsを圧迫putting pressureして窮状plightは深刻direとなっていた。

By actively utilizing

commercial capital, the power of large merchants who became privileged merchants

increased dramatically, but at the same time, commercial usury capital continued

to invade rural areas, putting pressure on farmers and local merchants. The

plight was dire.

また商業資本commercial capitalと結んだことで、幕府財政Shogunate financesの安定stabilizingと強化strengtheningには成功を収めたが、その反面、大商人large merchantsとの結びつきから賄賂(わいろ)briberyが公然と行われ、政治politicsの腐敗Corruption・堕落Fallを招き、士風の退廃decadence of the samuraiが目立った。

Also, by linking with

commercial capital, the Shogunate succeeded in stabilizing and strengthening

its finances, but on the other hand, bribery was openly carried out due to ties

with large merchants, leading to corruption and corruption of politics. The

decadence of the samurai was noticeable.

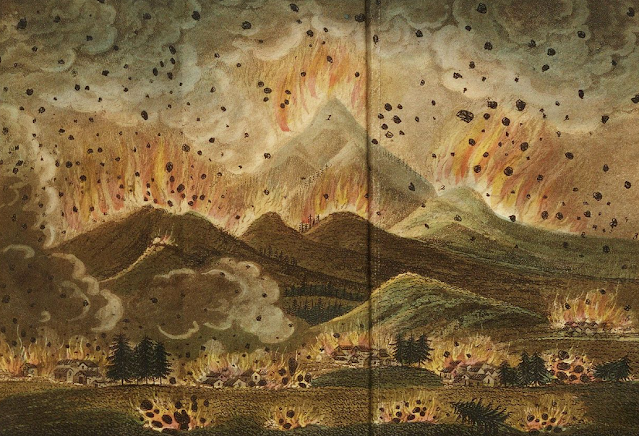

明和の大火(めいわ・の・たいか)Great Fire of

Meiwa

天明大噴火(てんめい・だいふんか)Tenmei

eruption

浅間山の噴火(あさまやま・の・ふんか)the eruption

of Mount Asama

天明大噴火(てんめい・だいふんか)Tenmei

eruption

浅間山の噴火(あさまやま・の・ふんか)the eruption

of Mount Asama

天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei

famine

農民収奪の強化the intensification

of farmers' expropriationに追い打ちをかけるように、各地で天災地変natural disastersが相次いで起こった。

As if to add insult to

injury to the intensification of farmers' expropriation, natural disasters

occurred one after another in various places.

1772年(明和9年)には、江戸Edo行人坂の大火(ぎょうにんざか・の・たいか)a great fire

at Gyoninzaka(明和の大火(めいわ・の・たいか)Great Fire of Meiwa)、風水害による凶作bad crops due to wind and flood damage、1783年(天明3年)には浅間山の噴火(あさまやま・の・ふんか)the eruption of Mount Asama(天明大噴火(てんめい・だいふんか)Tenmei eruption)や冷害(れいがい)damage from cold weatherが続き、数年間にわたり東北地方(とうほくちほう)Tōhoku regionをはじめ、全国across the countryに 数十万の餓死者hundreds of thousands of people starving to deathを出す惨状catastropheとなった(天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei famine)。

In 1772 (Meiwa 9), there

was a great fire at Gyoninzaka in Edo, and bad crops due to wind and flood

damage.In 1783 (Tenmei 3), the eruption of Mt. At first, it became a catastrophe

that left hundreds of thousands of people starving to death across the country

(the Great Tenmei Famine).

農民は土地を捨てて都市へ流入しFarmers abandoned their land and migrated to cities、あるいは、新生児を殺すculling newborn babies間引(まびき)Thinningの悪習the bad practiceがひろがった。

Farmers abandoned their

land and migrated to cities, and the bad practice of culling newborn babies

became widespread.

百姓一揆(ひゃくしょう・いっき)peasant

uprisings

また、各地で百姓一揆(ひゃくしょう・いっき)peasant uprisingsが激発し、天明(てんめい)年間だけduring

the Tenmei era aloneでも100件を越すほどであった。

In addition, peasant

uprisings broke out all over the country, and there were more than 100 peasant

uprisings during the Tenmei era alone.

田沼意知(たぬま・おきとも)Tanuma

Okitomo(1749~1784)

佐野政言(さの・まさこと)Sano Masakoto

このような社会混乱social turmoilのなかで、人々の不満people's dissatisfactionは田沼父子(たぬま・ふし)Tanuma father and sonに集中focusedした。

Amidst this social

turmoil, people's dissatisfaction focused on the Tanuma father and son.

1784年(天明4年)、田沼意知(たぬま・おきとも)Tanuma Okitomoが殿中(でんちゅう)the palaceで旗本(はたもと)Hatamoto佐野政言(さの・まさこと)Sano Masakoto(のち「世直し大明神(よなおし・だいみょうじん)Yonaoshi Daimyojin」と称せられた)の私怨private grudgeから斬られて死cut to deathに、1786年(天明6年)には、田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguも老中(ろうじゅう)Rōjū(Elder)を免ぜられて失脚expelled from the position of Roju and fell from graceした。

In 1784 (Tenmei 4),

Okitamo Tanuma was cut to death in the palace due to a private grudge against

Masakoto Sano (later known as 'Daimyojin'), and died in 1786 ( In the 6th year

of Tenmei (Tenmei 6), Okitsugu Tanuma was also expelled from the position of

Roju and fell from grace.

天明の打ちこわし(てんめい・の・うちこわし)Tenmei no Uchikoushi

翌1787年(天明7年)には、江戸Edo・大坂Osakaをはじめ各地で大規模な打ちこわしlarge-scale demolition(天明の打ちこわし(てんめい・の・うちこわし)Tenmei no Uchikoushi)が起こった。

The following year, 1787

(Tenmei 7), large-scale demolition (Tenmei no Uchikoushi) occurred in Edo, Osaka,

and other areas.

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)

8代将軍the 8th

shogun

享保の改革(きょうほう・の・かいかく)Kyōhō

Reformsのあと、幕藩体制(ばくはん・たいせい)the shogunate systemは本格的な危機a full-scale crisis(年貢増徴の限界limitations on annual tax increases・都市問題urban

problems・農村構造の変化changes in rural structureなど)に直面する。

After the Kyoho Reforms,

the shogunate system faced a full-scale crisis (limitations on annual tax

increases, urban problems, changes in rural structure, etc.).

田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma

Okitsugu(1719~1788)

しかし田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguは現実的な政治家a realistic politicianとして殖産興業策measures to promote new industriesと商業資本commercial

capitalを利用usingし大胆に対処dealt with the problemしたと積極的に評価positively evaluatedされる面もある。

However, Tanuma Okitsugu

has been positively evaluated as a realistic politician who boldly dealt with the

problem by using measures to promote new industries and commercial capital.

松浦静山(まつら・せいざん)Matsura

Seizan

今まで、賄賂bribery・士風頽廃corruptionが強調されてきているが、田沼意次(たぬま・おきつぐ)Tanuma Okitsuguの悪評the bad reputationも、その多くは政敵his political opponent松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuの政権下で生み出されたgeneratedものであり、権勢(けんせい)を実見・記録observed and recorded the powerしたという『甲子夜話(かっし・やわ)Kasshi Yawa』も、著者author松浦静山(まつら・せいざん)Matsura

Seizanは定信派the Sadanobu schoolに最も近い人物the person closest toであった。

Until now, emphasis has

been placed on bribery and corruption, but much of the bad reputation of

Okitsugu Tanuma was generated under the administration of Sadanobu Matsudaira,

his political opponent. Seizan Matsuura, the author of ``Koshi Yawa,'' which is

said to have observed and recorded the power, was the person closest to the

Teishin school.

徳川家治(とくがわ・いえはる)Tokugawa

Ieharu(在職1760~1786)

10代将軍the 10th shogun

徳川家重(とくがわ・いえしげ)Tokugawa

Ieshigeの子son

徳川家斉(とくがわ・いえなり)Tokugawa

Ienari(在職1787年~1837年)

11代将軍the 11th shogun

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)の曾孫great-grandson。

寛政の改革(かんせい・の・かいかく)

Kansei Reforms

10代将軍the 10th shogun徳川家治(とくがわ・いえはる)Tokugawa Ieharu(在職1760~1786)の死the death後、各地various placesで打ちこわしriotsが起こるなど騒然uproarとしたなかで、一橋家(ひとつばしけ)Hitotsubashi

Houseから15歳の徳川家斉(とくがわ・いえなり)Tokugawa Ienari(在職1787年~1837年)が11代将軍the 11th shogunに就任した。

After the death of the

10th shogun, Ieharu Tokugawa (1760-1786), there was an uproar, with riots

occurring in various places. ) became the 11th shogun.

田安宗武(たやす・むねたけ)Tayasu

Munetake

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)の次男second son。

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobu(1758~1829)

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimuneの孫grandson

これとともに、田安宗武(たやす・むねたけ)Tayasu Munetakeの子sonで、徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimuneの孫grandsonに当たる松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobu(1758~1829)(白河藩(しらかわ・はん)Shirakawa Domain(現在の福島県白河市) 11万石藩主(はんしゅ)lord of the Domain)が老中首座the head of the Rojuとなり、翌1788年(天明8年)には、将軍補佐役an

assistant to the shogunとなって幕政の改革reforming the shogunate governmentに当たった。

At the same time,

Sadanobu Matsudaira (1758-1829), the son of Tayasu Munetake and the grandson of

Tokugawa Yoshimune (lord of the Shirakawa domain with 110,000 koku of rice),

became the head of the Roju. The following year, 1788, he became an assistant

to the shogun and worked on reforming the shogunate government.

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)

8代将軍the 8th shogun

松平信明(まつだいら・のぶあきら)Matsudaira Nobuakira

本多忠籌(ほんだ・ただかず)Honda

Tadakazu

松平乗完(まつだいら・のりさだ)Matsudaira

Norisada

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobuは、享保の改革(きょうほう・の・かいかく)Kyōhō Reformsを模範とする復古政策a restoration policyを主眼とし、まず田沼派the Tanuma factionの幕吏the shogunate officialsを一掃するとともに松平信明(まつだいら・のぶあきら)・本多忠籌(ほんだ・ただかず)Honda Tadakazu・松平乗完(まつだいら・のりさだ)Matsudaira Norisadaら有能気鋭の人材talented and up-and-coming personnelを登用し、商業資本commercial

capitalとの結びつきを断ち切って田沼政治の腐敗浄化cleanse Tanuma's politics of corruptionに努めた。

Matsudaira Sadanobu

focused on a restoration policy modeled on the Kyoho Reforms, and first of all,

wiped out the shogunate officials of the Tanuma faction, as well as Nobuakira

Matsudaira and Tadashi Honda. Tadakazu, Matsudaira Norisada and other talented

and up-and-coming personnel were appointed, and efforts were made to sever ties

with commercial capital and cleanse Tanuma's politics of corruption.

極度の緊縮政策extreme

austerity policiesを基調とし、商業資本の抑圧suppressing commercial capital・農村の復興the reconstruction of rural areasによる貢租体系の再整備をreorganizing the tax systemはかって、幕藩体制(ばくはん・たいせい)the shogunate systemを再建reorganize・強化strengthenしようとした。

Based on extreme

austerity policies, they sought to reorganize and strengthen the shogunate system

by suppressing commercial capital and reorganizing the tax system through the

reconstruction of rural areas.

棄捐令(きえんれい)Kienrei(order of abandonment)

負債がたまり、札差(ふださし)Rice brokerらにその生活を支配されていた旗本(はたもと)Hatamoto・御家人(ごけにん)Gokeninの救済のため、松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuは1789年(寛政1年)、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateから低利で資金を貸す一方で、札差(ふださし)Rice brokerらに6年以前の債務を破棄destroy the debts of six years or earlierさせ、5年以内の債務the debts of

five years or lessについては利息を引き下げて年賦で返済させるよう命じた(棄捐令(きえんれい)Kienrei(order of abandonment))。

In 1789 (Kansei 1),

Matsudaira Sadanobu received a low interest rate from the shogunate in order to

save hatamoto and gokenin who had accumulated debts and had their lives

controlled by Fudasashi. At the same time, he ordered Fudasashi and others to

destroy the debts of six years or earlier, and to reduce the interest rate and

repay the debts in annual installments for the debts of five years or less.

しかし、この措置によって札差(ふださし)Rice brokerらの受けた損害は大きく、一時的に救われた旗本(はたもと)Hatamoto・御家人(ごけにん)Gokeninも、かえって金融の道が閉ざされたtheir financial avenues were closed offため、以前にまして困窮の度を深めた。

However, this measure inflicted great damage on the Fudasashi and others, and even the hatamotos and gokenins who had been temporarily saved found themselves in deeper poverty than before, as their financial avenues were closed off.

天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei

famine

天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei

famine以来、農村の荒廃は著しくrural areas have been severely devastated、それに伴って江戸に流れ込んだ人々が浮浪化vagrantsして、大きな社会問題a major social problemとなっていた。

Since the Great Tenmei

Famine, rural areas have been severely devastated, and people who have flowed

to Edo have become vagrants, which has become a major social problem.

石川島(いしかわ・じま)Ishikawa

Island人足寄場(にんそく・よせば)Ninsoku

Yoseba

このため1790年(寛政2年)、隅田川(すみだがわ)Sumida River(大川)河口の石川島(いしかわ・じま)Ishikawa Islandに人足寄場(にんそく・よせば)Ninsoku Yosebaを設け、人足寄場奉行の管理のもとに、無宿者homeless peopleや軽犯罪者petty criminalsで引取人がない者などを収容し、職業指導vocational guidanceを行った。

For this reason, in 1790

(Kansei 2), Ninsoku Yoseba was established on Ishikawa Island at the mouth of

the Sumida River (Okawa), and under the management of the Shinto Yoseba

Magistrate, homeless people and petty criminals were taken in. It housed people

who had no skills and provided them with vocational guidance.

七分積金(しちぶ・つみきん)Shichibutsumikin(70% deposit)

1791年(寛政3年)には、江戸市中の町費Edo City's town expenses(町入用(まち・にゅうよう)machi nyuyo)を節約savedさせ、その節約分の7割70% of the

savingsを町会所in the town hallに積み立てさせて、貧民の救済relief purposes for the poorや非常用for emergenciesの資金fundに当てさせた(七分積金(しちぶ・つみきん)Shichibutsumikin(70%

deposit))。

In 1791 (Kansei 3rd

year), Edo City's town expenses (machi nyuyo) were saved, and 70% of the

savings was set aside in the town hall for relief purposes for the poor and for

emergencies. It was given to the fund for

株仲間(かぶなかま)Kabunakama

運上金(うんじょうきん)unjokin・冥加金(みょうがきん)myogakin

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobuは、流通経済の抑圧suppressing the distribution economyと統制の強化strengthening

controlによって物価を安定stabilize pricesさせようとした。

Sadanobu Matsudaira tried

to stabilize prices by suppressing the distribution economy and strengthening

control.

そのため、運上金(うんじょうきん)unjokin・冥加金(みょうがきん)myogakinの徴収廃止the abolitionによって、財政収入が減少fiscal revenue would decreaseするにもかかわらず、あえて株仲間(かぶなかま)Kabunakamaの一部a portionを廃止abolishedした。

Therefore, despite the

fact that fiscal revenue would decrease due to the abolition of Unjokin and

Meikakin, a portion of Kabu Nakama was abolished.

囲米の制(かこいまい・の・せい)system of

rice engraving

1789年(寛政1年)、飢饉famineに備えて囲米の制(かこいまい・の・せい)system of rice engravingをしき、諸大名the feudal lordsに石高(こくだか)Kokudaka 1万石につき籾米(もみごめ)paddy rice 50石を貯蔵storeさせた。

In 1789 (1st year of the

Kansei era), in preparation for famine, a system of rice engraving was

introduced, and the feudal lords were forced to store 50 koku of paddy rice for

every 10,000 koku of koku.

また、各地various placesに社倉(しゃそう)shsōa・義倉(ぎそう)gisōを設けて飢饉famineに備えた。

In addition, shrines and

gisō were built in various places to prepare for famine.

旧里帰農令(きゅうり・きのう・れい)The Return to

Farm Order

荒廃した農村復興the

reconstruction of devastated rural areasのため農村人口の確保secure a rural populationと、農民の流入the influx of farmersによって膨張した都市貧民層the expansion of the urban poor対策のために、農民の都市への出稼ぎ・逃亡を禁止prohibited for farmers to migrate or flee to citiesするいっぽう、定職を持たない者people without regular jobsの都市からfrom cities農村への帰農を奨励encouraged

to return to farmingした(旧里帰農令(きゅうり・きのう・れい)The Return to Farm Order)。

In order to secure a

rural population for the reconstruction of devastated rural areas and to deal

with the expansion of the urban poor due to the influx of farmers, it is

prohibited for farmers to migrate or flee to cities, while at the same time

prohibiting people without regular jobs from moving from cities to rural areas.

encouraged to return to farming.

特に陸奥(むつ)Mutsu Province(福島県Fukushima Prefecture、宮城県Miyagi Prefecture、岩手県Iwate Prefecture、青森県Aomori Prefectureと秋田県Akita

Prefectureの一部)・常陸(ひたち)Hitachi Province(茨城県Ibaraki

Prefecture)・下野(しもつけ)Shimotsuke Province(栃木県Tochigi Prefecture)の三国the

three provincesなど、飢饉の被害が大きかった地方which were hit hard by the famineでは厳しく行われた。

In particular, it was strictly

enforced in the three provinces of Mutsu, Hitachi, and Shimotsuke, which were

hit hard by the famine.

奢侈禁止令(しゃし・きんし・れい)Sumptuary law

財政の窮迫the financial

crunchと生活の退廃the decadence of lifeの原因は奢侈(しゃし)luxuryにあるとして、旗本(はたもと)Hatamoto・御家人(ごけにん)Gokeninに倹約thriftyと武芸martial arts・学問academicsを奨励urgedした(奢侈禁止令(しゃし・きんし・れい)Sumptuary law)。

He urged hatamoto and

gokenin to be thrifty, martial arts and academics, blaming luxury as the cause

of the financial crunch and the decadence of life.

黄表紙(きびょうし)Kibyōshi

それは大名feudal lords・武士samuraiに止まらず、町人の日常生活の細部the details of the daily lives of townspeopleにも及んで、私娼(ししょう)private prostitutes・芸妓(げいぎ)geishaの取り締まりcrackdownsや混浴mixed bathing・賭博(とばく)gamblingの禁止prohibitionsをはじめ、黄表紙(きびょうし)Kibyōshi・洒落本(しゃれぼん)Sharebonなどの出版物Publicationsも、風俗を乱すdisrupt public moralsものとして統制controlledした。

This

is not limited to feudal lords and samurai, but also extends to the details of

the daily lives of townspeople, including crackdowns on private prostitutes and

geisha, prohibitions on mixed bathing and gambling, and bans on kibyoshi and

gambling. Publications such as pun books were also controlled as they were

thought to disrupt public morals.

洒落本(しゃれぼん)Sharebon

山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)

洒落本(しゃれぼん)Sharebon作家の山東京伝(さんとう・きょうでん)Santō Kyōden(1761~1816)は、手鎖(てぐさり)50日50 days in

chainsの処罰を受けた。

Santo Kyoden (1761-1816),

a storybook writer, was sentenced to 50 days in chains.

林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razan(道春(どうしゅん)Doshun)

元禄期the Genroku

period以降、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの儒官the Confucian officialsである林家(りんけ)the Rinke familyの朱子学(しゅしがく)Shushigaku(Cheng–Zhu school)は衰えて、聖堂学問所(せいどう・がくもんじょ)Seidō Gakumonjoの学風the academic cultureは停滞stagnantしていた。

After the Genroku period,

the Neo-Confucianism of the Hayashi family, the Confucian officials of the

shogunate, declined, and the academic culture of the Sejyo Gakko became

stagnant.

むしろ民間private schoolsの蘐園学派(けんえん・がくは)the Kenen school・陽明学派(ようめい・がくは)the Yomei schoolのほか、折衷学派(せっちゅう・がくは)the eclectic schoolなどの諸学派other schoolsが対立論争conflicts and debatesし、活況thrivedを呈した。

Rather, private schools such

as the Kenen school, the Yomei school, and other schools, such as the eclectic

school, clashed and thrived.

There were conflicts and

debates, and there was a lively atmosphere.

柴野栗山(しばの・りつざん)Shibano

Ritsuzan(1736~1807)

尾藤二洲(びとう・じしゅう)Bito Jishu(1747~1813)

岡田寒泉(おかだ・かんせん)Okada Kansen(1740~1816)

古賀精里(こが・せいり)Koga Seiri(1750~1817)

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobuは朱子学再興revive Neo-Confucianismのため、学問所the schoolに柴野栗山(しばの・りつざん)Shibano Ritsuzan(1736~1807)・尾藤二洲(びとう・じしゅう)Bito Jishu(1747~1813)・岡田寒泉(おかだ・かんせん)Okada Kansen(1740~1816)(寛政の三博士(かんせい・の・さんはかせ)Kansei's Three Doctors。のち岡田寒泉(おかだ・かんせん)に代わり古賀精里(こが・せいり)Koga Seiri(1750~1817))らを教官instructorsとして採用した。

Matsudaira Sadanobu

(1736-1807), Bito Jishu (1747-1813), Okada Kansen (1747-1813), and Shibano

Ritsuzan (1736-1807) set the school in order to revive Neo-Confucianism.

(1740-1816) (Kansei's Three Doctors. Later, Seiri Koga (1750-1817) replaced

Kansen Okada) and others as instructors.

寛政異学の禁(かんせい・いがく・の・きん)kansei igaku

no kin

また封建体制を維持maintain the feudal systemし、幕政の強化strengthen the shogunate governmentをはかるため、1790年(寛政2年)、柴野栗山(しばの・りつざん)Shibano Ritsuzanの建議proposalを入れ、朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismを正学(せいがく)the official schoolとし儒学諸派various schools of Confucianismを異学(いがく)different schoolsとして、聖堂学問所(せいどう・がくもんじょ)Seidō Gakumonjoでの講義を禁じprohibited lectures、朱子学(しゅしがく)の保護protected Neo-Confucianismをはかった(寛政異学の禁(かんせい・いがく・の・きん)kansei igaku no kin)。

In addition, in order to

maintain the feudal system and strengthen the shogunate government, in 1790,

Ritsuzan SHIBANO made a proposal to make Neo-Confucianism the official school

and categorize various schools of Confucianism into different schools. As a

result, he prohibited lectures at the Seido Gakumonjo and protected

Neo-Confucianism (Kansei Igaku no Kin).

大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしませいどう)Yushima Seidō)

昌平坂学問所(しょうへいざか・がくもんじょ)Shōhei-zaka

Gakumonjo

聖堂学問所(せいどう・がくもんじょ)Seidō

Gakumonjo

幕吏任用試験The

examination for the appointment of shogunate officialも朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismに限り、さらに聖堂学問所(せいどう・がくもんじょ)Seidō Gakumonjoも幕府管理下the control of the shogunateに移し、昌平坂学問所(しょうへいざか・がくもんしょ)Shōhei-zaka Gakumonjoと改められたrenamed。

The examination for the

appointment of shogunate official was limited to Neo-Confucianism, and the

temple school was also transferred to the control of the shogunate and renamed

Shohei-zaka Gakumonsho.

ロシアの南下Russia's

advance southward

千島列島(ちしま・れっとう)the Kuril Islands

蝦夷地(えぞち)Ezochi

厚岸町(あっけし・ちょう)Akkeshi-chō

ロシアRussiaは1730年代以降、次第に千島列島(ちしま・れっとう)the Kuril

Islandsに沿って南下moved southし、1778年(安永7年)にはロシア船a Russian shipが蝦夷地(えぞち)Ezochi厚岸(あっけし)Akkeshiに来航し、松前藩(まつまえ・はん)Matsumae Domainに通商tradeを求めた。

From the 1730s onward,

Russia gradually moved south along the Kuril Islands, and in 1778 (Yasun'ei 7),

a Russian ship came to Akkeshi in Ezoji and asked the Matsumae clan for trade.

アダム・ラクスマンAdam Laxman

また1792年(寛政4年)には、ラックスマンLaksman(1766年~?)が通商tradeを求めて根室(ねむろ)Nemuroに来航した。

Also, in 1792 (Kansei 4),

Laksman (1766-?) came to Nemuro in search of trade.

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobu(1758~1829)

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimuneの孫grandson

これらの情勢に対処In

response to these circumstancesして、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateでは、1791年(寛政3年)に松前藩(まつまえ・はん)Matsumae Domainに蝦夷地(えぞち)Ezochiの警備guardを命じ、諸藩the various domainsに異国船渡来the arrival of foreign shipsの際の処置を指令する一方、1792年(寛政4年)~1793年(寛政5年)、松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobu自ら安房(あわ)Awa Province・上総(かずさ)Kazusa Province・下総(しもうさ)Shimousa Province・伊豆(いず)Izu Province・相模(さがみ)Sagami Provinceの海岸coastsを巡視patrolledし、江戸湾の防備the defense of Edo Bayには幕府(ばくふ)the shogunate自身が当たることとし、沿岸諸藩the coastal domainsにも海防の強化strengthen their coastal defensesを命じた。

In response to these

circumstances, the shogunate ordered the Matsumae clan to guard Ezochi in 1791

(3rd year of Kansei era), ordered the various clans to deal with the arrival of

foreign ships, and in 1792 (4th year of Kansei era) ) ~ 1793 (Kansei 5),

Sadanobu Matsudaira himself patrolled the coasts of Awa, Kazusa, Shimousa, Izu,

and Sagami, and decided that the Shogunate would be responsible for the defense

of Edo Bay, He also ordered the domain to strengthen its coastal defenses.

林子平(はやし・しへい)Hayashi

Shihei(1738~1793)

三国通覧図説(さんごく・つうらん・ずせつ)Sangoku

Tsūran Zusetsu

ロシア南下Russia was

moving southwardの形勢the situationを見て、国防の要を痛感acutely aware of the importance of national defenseした林子平(はやし・しへい)Hayashi Shihei(1738~1793)は、1785年(天明5年)に『三国通覧図説(さんごく・つうらん・ずせつ)Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu』を著し、日本防衛the defense of Japanのため、蝦夷Ezo・朝鮮Korea・琉球Ryukyuの三国を確保secure the three countriesし、ロシアの南下Russia's move southwardに備えて蝦夷地開拓develop Ezo landの必要性needを説いた。

Hayashi Shihei

(1738-1793), who saw the situation in which Russia was moving southward and

became acutely aware of the importance of national defense, published the

"Illustrated Guide to the Three Kingdoms" in 1785 (Tenmei 5). He

wrote and advocated the need to secure the three countries of Ezo, Korea, and

Ryukyu for the defense of Japan, and to develop Ezo land in preparation for

Russia's move southward.

さらに1791年(寛政3年)には、『海国兵談(かいこく・へいだん)Kaikoku Heidan』を著して、外国に対する防備の必要the need for defense against foreign countriesを力説した。

Furthermore, in 1791

(Kansei 3), he wrote ``Kaikokuheidadan,'' emphasizing the need for defense

against foreign countries.

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobu(1758~1829)

徳川吉宗(とくがわよしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimuneの孫grandson

これに対して松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuは、翌1792年(寛政4年)、いたずらに民心を動揺させるupset the people's sentimentsものとして『海国兵談(かいこく・へいだん)Kaikoku Heidan』を絶版go out of print・発売禁止banned from saleにし、林子平(はやし・しへい)Hayashi Shiheiを禁固刑sentenced to imprisonmentに処した。

In response, Sadanobu

Matsudaira (1792) ordered Kaikokuheidan to go out of print and be banned from

sale, claiming that it would unnecessarily upset the people's sentiments. ,

Shihei Hayashi was sentenced to imprisonment.

アダム・ラクスマンAdam Laxman

ラックスマンLaksmanの来航arrivalは、林子平(はやし・しへい)Hayashi Shiheiが処罰された4か月後であった。

Laksman's arrival came

four months after Shihei Hayashi was punished.

大田南畝(おおた・なんぽ)Ōta Nanpo

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobuは緊縮政策austerity policyをとり、幕政の立て直しrebuild the shogunateに努力したが、それは時代に逆行するwent against the times反動の傾向reactionary tendencyが強く、幕府内部within the shogunateばかりでなく、「白河の清きに魚の住みかねて もとの濁りの田沼こひしきFish can no longer live in the clear waters of Shirakawa, and Tanuma

Kohishiki remains as murky as before.」、「世の中に蚊ほどうるさきものはなし ぶんぶ(文武)といふて夜もねられずThere's nothing in the world as noisy as a mosquito, and I can't

sleep at night because it's called Bunbu.」(大田南畝(おおた・なんぽ)Ōta Nanpo)と狂歌(きょうか)Kyōkaにもうたわれたように、庶民の反発backlash from the common peopleも招いた。

Sadanobu Matsudaira

adopted an austerity policy and made efforts to rebuild the shogunate, but this

had a strong reactionary tendency that went against the times. As in the kyōka

poems, such as ``Middy Tanuma Kohishiki'' and ``There is nothing as noisy as a

mosquito in the world, even at night, even if you say Bunbu (Bunbu)'' (Ota

Nanpo), there was a backlash from the common people. also invited.

徳川家斉(とくがわ・いえなり)Tokugawa

Ienari(在職1787年~1837年)

11代将軍the 11th shogun

一橋家(ひとつばしけ)Hitotsubashi

House

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)の曾孫great-grandson。

また、徳川家斉(とくがわ・いえなり)Tokugawa Ienariが成長grew upして松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuの存在がうとんぜられるようになってきたexistence began to be ignoredこともあって、1793年(寛政5年)、伊豆(いず)Izu Province(静岡県Shizuoka

Prefecture)・相模(さがみ)Sagami Province(神奈川県(かながわけん)Kanagawa Prefecture)の沿岸巡視中on a tour of the coast of、松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuは老中首座head of the Roju・将軍補佐役assistant to the shogunを免ぜられrelieved、失脚fell from graceした。

In addition, as Ienari

Tokugawa grew up and Matsudaira Sadanobu's existence began to be ignored, in

1793 (Kansei 5), Matsudaira Sadanobu was on a tour of the coast of Izu and

Sagami. He was relieved of his position as head of the Roju and assistant to

the shogun, and fell from grace.

松平信明(まつだいら・のぶあきら)Matsudaira Nobuakira

水野忠成(みずの・ただあきら)Mizuno Tadaakira

しかし、以降も松平信明(まつだいら・のぶあきら)Matsudaira Nobuakiraら松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira Sadanobuと密接なつながりclose tiesを持ついわゆる「寛政の遺老(かんせい・の・いろう)Kansei elders」たちが政権を担当in charge of the governmentし、1818年に水野忠成(みずの・ただあきら)Mizuno Tadaakira政権governmentが誕生するまで、改革の基本路線the fundamentals of reformは継続した。

However, from then on,

the so-called "Kansei elders" who had close ties to Matsudaira

Sadanobu, such as Nobuaki Matsudaira, were in charge of the government, and

until the Tadakira Mizuno government was established in 1818, the fundamentals

of reform remained unchanged. The route continued.

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobu(1758~1829)

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimuneの孫grandson

松平定信(まつだいら・さだのぶ)Matsudaira

Sadanobuは、農村支配の強化のため荒廃した農村の復興rebuild devastated farming villagesをはかり、また商業資本を抑圧suppressing commercial capitalすることによって本百姓(ほんびゃくしょう)Honbyakushōの解体the dissolutionを防止し、幕藩体制の危機the crisis of the shogunate systemを乗り切ろうとした。

Sadanobu Matsudaira tried

to rebuild devastated farming villages in order to strengthen his control over

them, prevent the dissolution of honhyakusho by suppressing commercial capital,

and try to overcome the crisis of the shogunate system.

しかし、これら保守的・反動的色彩の濃い、極端な緊縮政策extreme austerity policiesや思想・言論の統制control of thought and speechは、一時的な幕政の立て直しは成しえてもeven if the shogunate could be temporarily rebuilt、根本的に解決fundamentally solvedすることはできなかった。

However, these

conservative and reactionary extreme austerity policies and control of thought

and speech could not be fundamentally solved, even if the shogunate could be

temporarily rebuilt.

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa

Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)

8代将軍the 8th shogun

享保の改革(きょうほう・の・かいかく)Kyoho Reforms・寛政の改革(かんせい・の・かいかく)Kansei Reformsは、農村の回復the recovery of rural villagesを重要な課題an important issueにしてきたが、それにもかかわらず、18世紀~19世紀にかけて農村rural

villagesは荒廃devastatedに直面した。

The Kyoho Reforms and the

Kansei Reforms made the recovery of rural villages an important issue, but despite

this, rural villages were devastated during the 18th and 19th centuries. faced.

農民Farmersは、領主の租税引き上げthe lord's tax hikesと定免法(じょうめんほう)A fixed exemption lawの採用や商品経済の流入the influx of the commodity economyで生活が苦しくなり、田畑を質入れしてpawned their fields(事実上の売却)小作(こさく)tenant farmersに転落する者、離村して都市下層民the lower class peopleになる者などが現れ、代わって寄生地主(きせい・じぬし)parasitic landlordsなどが成長してきていた。

Farmers' lives became

difficult due to the lord's tax hikes, the introduction of fixed exemption

laws, and the influx of the commodity economy, and some pawned their fields

(effectively sold them) and became tenant farmers, while others left their

villages and moved to cities. Those who became the lower class people appeared,

and parasitic landlords and others were growing on their behalf.

享保の大飢饉(きょうほう・の・だいききん)Great Kyōhō

famine(1732年)

天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei

famine(1782年~1787年)

天保の大飢饉(てんぽう・の・だいききん)Great Tenpō famine(1833年~1839年)

天保の大飢饉(てんぽう・の・だいききん)Great Tenpō famine(1833年~1839年)

しばしば起こる凶作crop failures・飢饉faminesは、人々の生活people's livesをいっそう苦しいものにした。

The frequent crop

failures and famines made people's lives even more difficult.

なかでも享保の大飢饉(きょうほう・の・だいききん)Great Kyōhō famine(1732年)・天明の大飢饉(てんめい・の・だいききん)Great Tenmei famine(1782年~1787年)・天保の大飢饉(てんぽう・の・だいききん)Great Tenpō famine(1833年~1839年)は、その被害damageが全国的に及んで甚(はなは)だしく、近世後期の三大飢饉the three major famines of the late modern period(江戸三大飢饉(えど・さんだい・ききん)Three Great

famines in the Edo period)と言われている。

Among these, the Kyoho

famine (1732), Tenmei famine (1782-1787), and Tenpo famine (1833-1839) caused

severe damage throughout the country. , is said to be one of the three major

famines of the late modern period.

商人merchants・地主landownersは凶作the bad

harvestになると穀物の買占めbought up grainや売り惜しみheld off on selling itをして、米価の高騰the price of rice to soarを招き、多数の餓死者many deaths from starvationを出すなど被害damageをさらに大きくした。

When the harvest went

bad, merchants and landowners bought up grain or held off on selling it,

causing the price of rice to soar, causing many deaths from starvation, and

causing even more damage.

農村人口の減少the decline

in the rural populationは農業生産力を低下a decline in agricultural productivityさせ、農村の荒廃the

devastation of rural areasをいっそう促した。

The decline in the rural

population led to a decline in agricultural productivity and further accelerated

the devastation of rural areas.

百姓一揆(ひゃくしょう・いっき)peasant

uprisings

このような窮乏に堪えかねた農民farmers who could not endure such povertyのうちから、次第に百姓一揆(ひゃくしょう・いっき)Farmers' uprisingsも起こり始めたbegan to occur。

Farmers' uprisings began

to occur among farmers who could not endure such poverty.

やがて飢饉faminesが頻繁に続くと、各地in various placesで百姓一揆(ひゃくしょう・いっき)peasant uprisingsが一段と激しくなったintensified。

Before long, famines

continued frequently, and peasant uprisings intensified in various places.

天明の打ちこわし(てんめい・の・うちこわし)Tenmei no Uchikoushi

また都市citiesでも、没落fallして農村farming villagesから流入flowed inした貧民poor peopleたちが、圧政tyrannyや米価高騰soaring rice pricesに対して、富裕な米屋wealthy rice dealersや高利貸loan sharksを襲撃attackし、米riceや借金証文loan certificatesなどを奪うstealing打ちこわしUchikoushiが、18世紀後半the late 18th

centuryから頻発し始めたbegan to occur frequently。

Also, in the cities, poor people who flowed in from farming villages after the fall began to attack wealthy rice dealers and loan sharks in response to oppression and soaring rice prices.