日本史20 Japanese history 20

室町文化 Muromachi culture

北山山荘(きたやま・さんそう)Kitayama mountain

villa

鹿苑寺(ろくおんじ)Rokuon-ji 金閣寺(きんかくじ)Kinkaku-ji

東山山荘(ひがしやま・さんそう)Higashiyama mountain

villa

慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishō-ji 銀閣寺(ぎんかくじ)Ginkaku-ji

足利尊氏(あしかが・たかうじ)Ashikaga

Takauji(1305年~1358年)(53歳)

後醍醐天皇(ごだいご・てんのう)Emperor

Go-Daigo

第6章 Chapter 6

大名領国制の形成

Formation of the Feudal

lord system

第6節 Section 6

室町文化Muromachi

culture

文化の時代区分Cultural era

division

足利尊氏(あしかが・たかうじ)Ashikaga

Takaujiが「建武式目(けんむ・しきもく)Kenmu shikimoku」を発布promulgatedした1336年(建武3年・延元1年)、または征夷大将軍(せいい・たいしょうぐん)Sei-i Taishōgunになった1338年(暦応1年)から1573年(天正1年)の室町幕府(むろまち・ばくふ)Muromachi shogunate滅亡fallまで、約240年間を室町時代(むろまち・じだい)Muromachi periodと言う。

The Muromachi period is

about 240 years, from 1336 when Takauji Ashikaga promulgated the 'Kenmu

Shikimoku' (Kenmu Shikimoku), or from 1338 when he became Seii Taishogun to the

fall of the Muromachi shogunate in 1573.

そのうち、1336年(建武3年・延元1年)の後醍醐天皇(ごだいご・てんのう)Emperor Go-Daigoの吉野遷幸(よしの・せんこう)transfer of Yoshinoから1392年(明徳3年)の南北朝の合一(なんぼくちょう・の・ごういつ)the

unification of the Northern and Southern Courtsまでを南北朝時代(なんぼくちょう・じだい)Northern and

Southern Courts periodとし、それ以後を室町時代(むろまち・じだい)Muromachi periodと狭義narrowly definedに用いる説もある。

Among them, there is a

theory that the period from Emperor Godaigo's transfer of Yoshino in 1336 to

the unification of the Northern and Southern Courts in 1392 is regarded as the

period of the Northern and Southern Courts, and the period after that is

narrowly defined as the Muromachi period.

さらにこの狭義narrowly definedの室町時代(むろまち・じだい)Muromachi periodのうち、応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin War後から室町幕府(むろまち・ばくふ)Muromachi shogunate滅亡fallまでの約1世紀 about

one centuryを戦国時代(せんごく・じだい)Sengoku

period(Warring

States period)と呼んで区別することもある。

Furthermore, within this

narrowly defined Muromachi period, the period of about one century from the end

of the Onin War to the fall of the Muromachi bakufu is sometimes called the

Sengoku period.

足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga

Yoshimitsu(在職1368~1394)

北山山荘(きたやま・さんそう)Kitayama mountain

villa

鹿苑寺(ろくおんじ)Rokuon-ji 金閣寺(きんかくじ)Kinkaku-ji

約240年間の室町文化(むろまち・ぶんか)Muromachi cultureには二つの頂点two peaksがあった。

There were two peaks in

Muromachi culture for about 240 years.

一つは足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsu(在職1368~1394)の北山山荘(きたやま・さんそう)Kitayama mountain villaに代表される北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama cultureで、足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuや守護(しゅご)Shugoや一部の公家court noblesたちを中心に、1400年前後に花開いたblossomed文化cultureである。

One is the Kitayama

culture represented by Yoshimitsu Ashikaga (1368-1394)'s Kitayama Sanso, a

culture that blossomed around 1400, centered around Yoshimitsu Ashikaga, Shugo,

and some court nobles.

伝統的公家文化traditional

aristocratic cultureと新興の武家文化emerging samurai cultureを融合fusesし、中国の文化Chinese cultureを取り入れ、禅宗文化(ぜんしゅう・ぶんか)Zen Buddhism cultureを基調としたものである。

It fuses traditional aristocratic

culture with emerging samurai culture, incorporates Chinese culture, and is

based on Zen Buddhism culture.

足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasa(在職1449~1473)

東山山荘(ひがしやま・さんそう)Higashiyama mountain

villa

慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishō-ji 銀閣寺(ぎんかくじ)Ginkaku-ji

いま一つの東山文化(ひがしやま・ぶんか)Higashiyama cultureは、足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasa(在職1449~1473)の東山山荘(ひがしやま・さんそう)Higashiyama mountain villaに代表される文化cultureで、応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warをよそにして、足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaを中心に北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama cultureの伝統traditionを受け継ぎinheritingながら、新興の庶民文化the new common people's cultureを濃く吸収deeply absorbedした文化cultureである。

Another Higashiyama

culture is represented by the Higashiyama villa of Yoshimasa Ashikaga

(1449-1473).

Aside from the Onin War,

it is a culture that has deeply absorbed the new common people's culture while inheriting

the Kitayama culture centered on Yoshimasa Ashikaga.

婆娑羅(ばさら)Basara

幽玄(ゆうげん)Yūgen(趣きが深く、高尚で優美なこと)(Tasteful, noble and graceful)や侘(わび)Wabi(貧粗・不足のなかに心の充足をみいだそうとする意識)(Consciousness that seeks to find fulfillment in the midst of poverty

and insufficiency)・寂(さび)Sabi(閑寂さのなかに、奥深いものや豊かなものがおのずと感じられる美しさ)(The beauty of being able to feel the depth and richness of nature in

silence)などの余情(よじょう)afterthought(あとまで残っている、印象深いしみじみとした味わい)(Impressive and deep taste that remains in the aftertaste)と簡素simplicityを重んじたemphasized美意識aesthetic senseと、華美で珍奇な趣きをこらしたExuding a gorgeous and unusual taste現世謳歌luxuries of this worldの奢侈(しゃし)な風潮extravagant

trend(=婆娑羅(ばさら)Basara)が発達developedした。

An aesthetic sense that

emphasized the afterthought and simplicity, such as Yugen, Wabi, and Sabi, and an extravagant

trend (=basara) of the luxuries of this world that emphasized gorgeousness and

curiosity developed.

この北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama culture・東山文化(ひがしやま・ぶんか)Higashiyama cultureは、直接的には京都に育ったdirectly brought up in Kyotoが、大切なことwhat is importantはそれが地方にも伝えられtransmitted to the regions、それぞれの時代の文化の基調the basis of the culture of each eraとなったことである。

This Kitayama culture and

Higashiyama culture were directly brought up in Kyoto, but what is important is

that they were transmitted to the regions and became the basis of the culture

of each era.

南禅寺(なんぜんじ)Nanzen-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City左京区(さきょうく)Sakyō-ku

無関普門(むかん・ふもん)Mukan Fumon(大明国師(だいみょう・こくし)Daimyo Kokushi)

臨済宗の興隆Rise of the

Rinzai sect

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolは歴代足利将軍successive Ashikaga shogunsや守護大名(しゅご・だいみょう)Shugo-daimyō、また公家court noblesの一部の帰依(きえ)Refuge in Buddhismを受け、南北朝期the period of the Northern and Southern Courtsから室町初期the

early Muromachi periodにかけ全盛期heydayを迎えた。

The Rinzai sect reached

its heyday from the period of the Northern and Southern Courts to the early

Muromachi period, receiving the faith of successive Ashikaga shoguns, shugo

daimyo, and some court nobles.

特に五山(ござん)Five Mountains・十刹(じっさつ)Ten Monasteriesに指定された寺院templesは、幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの官寺(かんじ)となって保護protectionを受け、五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅僧Zen priestsは幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの政治・外交の顧問political and diplomatic advisorsとして活躍した。

In particular, temples

designated as Gozan and Jissetsu became official temples of the shogunate and

received protection, and Zen priests of Gozan played active roles as political

and diplomatic advisors to the shogunate.

妙心寺(みょうしんじ)Myōshin-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City右京区(うきょうく)Ukyō-ku

関山慧玄(かんざん・えげん)Kanzan Egen

彼らは、座禅(ざぜん)Zazen(seated meditation)そのものは軽視し、むしろ五山文学(ござん・ぶんがく)Literature of the Five Mountains・水墨画(すいぼくが)Ink wash paintingなど北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama culture・東山文化(ひがしやま・ぶんか)Higashiyama cultureの中心の場での働きが注目される。

They disregarded zazen

itself, and rather paid attention to their work at the center of Kitayama

culture and Higashiyama culture, such as Gozan literature and ink painting.

大徳寺(だいとくじ)Daitoku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City北区(きたく)Kita-ku

宗峰妙超(しゅうほう・みょうちょう)Shuho Myocho(大燈国師(だいとう・こくし)Daitō Kokushi)

そして、応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warによって幕府権力the power of the shogunateが衰えたweakenedのを契機に、五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅宗(ぜんしゅう)Zen Buddhismも衰え、代わって同じ臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolでありながら五山(ござん)Five Mountainsに属さない妙心寺(みょうしんじ)Myōshin-jiや大徳寺(だいとくじ)Daitoku-ji、それに曹洞宗(そうとうしゅう)Sōtō schoolの禅(ぜん)Zenが、在野の立場に立って林下(りんか)Rinka(the forest below)(禅寺のうち、在野の寺院を指す)(Among Zen temples, it refers to temples that are out of the field.)の禅(ぜん)Zenと言われ、庶民commonersや地方武士local

samuraiのなかに勢力をもって室町後期the latter half of the Muromachi periodに発展developedした。

The Onin War weakened the

power of the shogunate, and the Zen sects of the Gozan sects also declined.

Known as Rinka no Zen, it developed in the latter half of the Muromachi period,

gaining influence among commoners and local samurai.

後小松天皇(ごこまつ・てんのう)Emperor

Go-Komatsu

第100代天皇the 100th emperor(在位1382年~1412年)

北朝(ほくちょう)Northern

Court第6代天皇the sixth Emperor

後円融天皇(ごえんゆう・てんのう)Emperor

Go-En'yūの第一皇子the First son

北朝(ほくちょう)Northern

Court(持明院統(じみょういん・とう)Jimyōin-tō)

禅僧Zen monk一休宗純(いっきゅう・そうじゅん)Ikkyū Sōjunは後小松天皇(ごこまつ・てんのう)Emperor Go-Komatsuの落胤the illegitimate sonと伝わる。

一休宗純(いっきゅう・そうじゅん)Ikkyū Sōjun(1394~1481)

後小松天皇(ごこまつ・てんのう)Emperor

Go-Komatsuの落胤the illegitimate son

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warの頃、堺(さかい)Sakaiの町衆the townspeopleに庶民禅Zen for

the commonersを説いた大徳寺(だいとくじ)Daitoku-jiの一休宗純(いっきゅう・そうじゅん)Ikkyū Sōjun(1394~1481)はその代表である。

Ikkyu Sojun (1394-1481)

of Daitokuji Temple, who preached Zen to the commoners of Sakai during the Onin

War, is a representative example.

夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Soseki(1275~1351)

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

天龍寺(てんりゅうじ)Tenryū-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City右京区(うきょうく)Ukyō-ku嵯峨(さが)Saga

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozan

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolは、特に幕府(ばくふ)Shogunate上層部the upper

echelonsと結びついてconnecting勢力を伸ばした。

The Rinzai sect, in

particular, expanded its influence by connecting with the upper echelons of the

bakufu.

足利尊氏(あしかが・たかうじ)Ashikaga

Takaujiは一山一寧(いっさん・いちねい)Issan Ichineiの弟子disciple夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Soseki(1275~1351)に深く帰依(きえ)Refuge in Buddhismし、後醍醐天皇(ごだいご・てんのう)Emperor Go-Daigoの冥福を祈るpray for the repose of the soulため、1339年(暦応2年)から京都(きょうと)Kyotoに天龍寺(てんりゅうじ)造営工事construction

workをおこし、夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Sosekiを開山(かいさん)Kaisan(創立者founder)とした。

Ashikaga Takauji became a

devotee of Muso Soseki (1275-1351), a disciple of Ichizan Ichinei, and in order

to pray for the repose of the soul of Emperor Godaigo, began construction work

on Tenryu-ji Temple in Kyoto in 1339 and established Muso Soseki.

安国寺(あんこくじ)Ankoku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

また足利尊氏(あしかが・たかうじ)Ashikaga Takaujiは、元弘の変(げんこう・の・へん)Genkō Incident以来の戦没者の霊the spirits of the war deadを慰めるcomfortため、諸国each provinceに一寺one temple・一塔one towerの臨済禅寺Rinzai Zen templesを建てた。

In addition, Takauji Ashikaga

built Rinzai Zen temples with one temple and one tower in each province to

comfort the spirits of the war dead since the Genko Incident.

これを安国寺(あんこくじ)Ankoku-ji・利生塔(りしょうとう)Rishotoと言う。

This is called Ankokuji

and Rishoto.

足利直義(あしかが・ただよし)Ashikaga Tadayoshi(1306~1352)

足利尊氏(あしかがたかうじ)Ashikaga

Takaujiの弟younger brother

また『夢中問答(むちゅう・もんどう)Muchū Mondō』は、夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Sosekiが足利直義(あしかが・ただよし)Ashikaga Tadayoshiの問いに答えた法話集a collection of sermonsで、在家(ざいけ)zaikeの女性womenや仏道を志す者those who aspire to Buddhismのため禅(ぜん)Zenを易しく説いたexplains Zen in an easy-to-understand mannerものである。

In addition, "Dreaming

Conversation" is a collection of sermons in which Muso Soseki answers

questions asked by Ashikaga Tadayoshi, and explains Zen in an

easy-to-understand manner for lay women and those who aspire to Buddhism.

相国寺(しょうこくじ)Shōkoku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City上京区(かみぎょうく)Kamigyō-ku

夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Soseki

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozan

春屋妙葩(しゅんおく・みょうは)Shun’oku

Myōha(1311~1388)

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

義堂周信(ぎどう・しゅうしん)Gidō Shūshin(1325~1388)

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

絶海中津(ぜっかい・ちゅうしん)Zekkai

Chūshin(1336~1405)

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

夢窓疎石(むそう・そせき)Musō Sosekiの門下disciplesからは優れた禅僧outstanding

Zen monksが多く出たが、彼らはいずれも幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの政治顧問political advisorsや外交の補佐diplomatic assistants、あるいは詩文の分野poetry writersで活躍activeした。

Muso Soseki's disciples

produced many outstanding Zen monks, all of whom were active as political

advisors to the shogunate, diplomatic assistants, or poetry writers.

取り分け、足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuの相国寺(しょうこくじ)Shōkoku-ji造営constructionに尽力contributedした春屋妙葩(しゅんおく・みょうは)Shun’oku Myōha(1311~1388)、詩文集collection of poems『空華日工集(くうげ・にっくしゅう)Kuge Nikkushū』で知られる義堂周信(ぎどう・しゅうしん)Gidō Shūshin(1325~1388)、それに絶海中津(ぜっかい・ちゅうしん)Zekkai Chūshin(1336~1405)らが有名である。

In particular, Haruya

Myoha (1311-1388), who contributed to the construction of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu's

Shokokuji Temple, Gido Shushin (1325-1388), known for his collection of poems

Kuugenickushu, and Zekkai Nakatsu. 1336-1405) are famous.

建仁寺(けんにんじ)Kennin-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City東山区(ひがしやまく)Higashiyama-ku

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozan

鎌倉五山(かまくら・ござん)Kamakura Gozan

臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolに帰依(きえ)Refuge in Buddhismした足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuは、将軍家菩提寺the family temple of the shogun familyとして花の御所(はな・の・ごしょ)Hana no Goshoの隣地に相国寺(しょうこくじ)Shōkoku-jiを造営し、次いで1386年(至徳3年)、京都(きょうと)Kyotoと鎌倉(かまくら)Kamakuraの禅寺Zen templesに五山の制(ござん・の・せい)Five Mountain Systemを整備し、さらに十刹の制(じっさつ・の・せい)Ten Monasteries Systemも整えて、主要な臨済禅寺Rinzai Zen templesを官寺化turned into an official templeして幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの保護protection・統制controlのもとに置いた。

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, a

devotee of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism, built Shokokuji Temple next to Hananogosho

as the family temple of the shogun family. Rinzai Zen-ji Temple was turned into

an official temple and placed under the protection and control of the shogunate.

こうして室町時代(むろまち・じだい)Muromachi periodの臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolの大勢は、座禅(ざぜん)Zazen(seated meditation)や公案(こうあん)Koanにふける禅(ぜん)Zen本来の姿original formを失い、幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの支配体制the ruling systemの一環part ofたる地位positionを占めるようになった。

In this way, the majority

of the Rinzai sect in the Muromachi period lost its original form of Zen,

indulging in zazen and koan, and came to occupy a position as part of the

ruling system of the shogunate.

東福寺(とうふくじ)Tōfuku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City東山区(ひがしやまく)Higashiyama-ku

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozan

五山・十刹の制(ござん・じっさつ・の・せい)Five

Mountains and Ten Monasteries Systemは宋(そう)the Song Dynastyの禅寺の制Zen

temple systemを移入introducedしたもので、日本Japanでは鎌倉時代(かまくら・じだい)Kamakura periodに始まる。

The Gozan/Jissatsu system

was introduced from the Zen temple system of the Song dynasty, and began in

Japan in the Kamakura period.

もっとも、指定される寺院designated templesやその順位their ranksにはしばしば移動changedがあり、確立establishedしたのは足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuによる1386年(至徳3年)のことである。

However, the designated

temples and their ranks often changed, and they were established in 1386 by

Yoshimitsu ASHIKAGA.

万寿寺(まんじゅじ)Manju-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City東山区(ひがしやまく)Higashiyama-ku

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozan

五山(ござん)Five Mountainsとは、はじめは禅宗(ぜんしゅう)Zen Buddhismの五大官寺Five Great Official Templesの意であったが、ここでは禅寺の最高の寺格the highest rank of Zen temples、十刹(じっさつ)Ten Monasteriesはそれに次ぐ寺格the second rank of Zen templesを意味する。

Gozan originally meant

the Five Great Official Temples of Zen Buddhism, but here Jissatsu, the highest

rank of Zen temples, means the second rank.

従って、5か寺または10か寺と限らない。

Therefore, it is not

limited to 5 temples or 10 temples.

建長寺(けんちょうじ)Kenchō-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

鎌倉市(かまくらし)Kamakura City山ノ内(やまのうち)Yamanouchi

蘭渓道隆(らんけい・どうりゅう)Rankei Dōryū

鎌倉五山(かまくら・ござん)Kamakura Gozan

足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga

Yoshimitsuは南禅寺(なんぜんじ)Nanzen-jiを五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの上に置き、

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

placed Nanzenji on top of the five mountains,

京都五山(きょうと・ござん)Kyoto Gozanを天龍寺(てんりゅうじ)Tenryū-ji・相国寺(しょうこくじ)Shōkoku-ji・建仁寺(けんにんじ)Kennin-ji・東福寺(とうふくじ)Tōfuku-ji・万寿寺(まんじゅじ)Manju-ji、

Tenryu-ji Temple,

Shokoku-ji Temple, Kennin-ji Temple, Tofukuji Temple, Manju-ji Temple,

鎌倉五山(かまくら・ござん)Kamakura Gozanを建長寺(けんちょうじ)Kenchō-ji・円覚寺(えんがくじ)Engaku-ji・寿福寺(じゅふくじ)Jufuku-ji・浄智寺(じょうちじ)・浄妙寺(じょうみょうじ)と定めた。

Kenchoji, Engakuji,

Jufukuji, Jochiji, and Jyomyoji are the five Kamakura Gozan.

円覚寺(えんがくじ)Engaku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

鎌倉市(かまくらし)Kamakura City山ノ内(やまのうち)Yamanouchi

宋(そう)the Song Dynasty 無学祖元(むがく・そげん)Mugaku Sogen

鎌倉五山(かまくら・ござん)Kamakura Gozan

また足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuは僧録の制(そうろく・の・せい)soroku systemを定め、春屋妙葩(しゅんおく・みょうは)Shun’oku Myōhaを初代の僧録司(そうろくし)sorokushiに任命appointedし、将軍直属として、五山・十刹(ござん・じっさつ)Five Mountains and Ten Monasteriesの住持任免appoint

and dismiss the chief priestや寺領管理manage the temple territoryを行わせたので、臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai schoolのうち五山・十刹(ござん・じっさつ)Five Mountains and Ten Monasteriesの諸寺each templeは、官寺化converted

into government templesした。

Yoshimitsu Ashikaga established

the soroku system and appointed Myoha Haruya as the first sorokushi, reporting

directly to the shogun and having him appoint and dismiss the chief priest of

the Gozan and Jissetsu temples, as well as manage the temple territory.

Jissetsu temples were converted into government temples.

寿福寺(じゅふくじ)Jufuku-ji 臨済宗(りんざいしゅう)Rinzai school

鎌倉市(かまくらし)Kamakura City扇ヶ谷(おうぎがやつ)Ōgigayatsu

栄西(えいさい)Eisai(1141~1215)

鎌倉五山(かまくら・ござん)Kamakura Gozan

ここに五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅僧Zen monksが、室町幕府(むろまち・ばくふ)Muromachi shogunateの政治・外交上の顧問political and diplomatic advisorsとして活躍play

active rolesする素地groundworkが作られた。

This laid the groundwork

for Zen monks from the Gozan to play active roles as political and diplomatic

advisors to the Muromachi Shogunate.

中厳円月(ちゅうがん・えんげつ)Chūgan

Engetsu

岐陽方秀(きよう・ほうしゅう)Kiyou Hoshu

禅(ぜん)Zen本来の精神鍛錬the original mental trainingを失った五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅僧Zen monksは、室町時代(むろまち・じだい)Muromachi

periodには学問や文学の面で活躍active in academics and literatureした。

The Zen monks of the

Gozan, who had lost the original mental training of Zen, were active in academics

and literature during the Muromachi period.

鎌倉時代(かまくら・じだい)Kamakura periodにわが国に伝えられた宋学(そうがく)The study of the Song Dynasty(朱子学(しゅしがく)Cheng–Zhu school)は、五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅僧Zen monksに引き継がれ、五山(ござん)Five Mountainsは室町期Muromachi periodの宋学(そうがく)The study of the Song Dynasty(朱子学(しゅしがく)Cheng–Zhu school)の中心となり、中厳円月(ちゅうがん・えんげつ)Chūgan Engetsu・義堂周信(ぎどう・しゅうしん)Gidō Shūshin・岐陽方秀(きよう・ほうしゅう)Kiyou Hoshuら多くの学僧learned monksが現れ、近世朱子学勃興the rise of modern Neo-Confucianismの源流sourceとなった。

The study of Song dynasty

(Shushigaku) introduced to Japan in the Kamakura period was passed on to the

Zen priests of the Five Mountains. Hoshu) and many learned monks appeared, and

became the source of the rise of modern Neo-Confucianism.

五山文学(ござん・ぶんがく)Literature of

the Five Mountains

また五山(ござん)Five Mountainsの禅僧Zen monksの間に漢詩文Chinese poetryが流行became popularし、五山文学(ござん・ぶんがく)Literature of the Five Mountainsと呼ばれた。

In addition, Chinese

poetry became popular among the Zen monks of the Gozan, and it was called Gozan

literature.

五山文学(ござん・ぶんがく)Literature of

the Five Mountainsは足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuの頃、義堂周信(ぎどう・しゅうしん)Gidō Shūshinや絶海中津(ぜっかい・ちゅうしん)Zekkai Chūshinが出て全盛期its peakを迎え、その後衰えながらも戦国時代(せんごく・じだい)Sengoku period(Warring

States period)まで持続し、この間に多くの詩文僧poetic priestsが輩出した。

Gozan Bungaku reached its

peak around the time of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, with Gido Shushin and Zekkai

Nakatsu appearing, and although it declined thereafter, it continued until the

Warring States period, during which many poetic priests emerged.

また五山(ござん)Five Mountainsからは、禅の経典Zen scripturesや儒書Confucian books・詩文poetry・辞典dictionariesなどが盛んに出版actively publishedされて五山版(ござんばん)the Gozan Editionと呼ばれ、漢詩文Chinese poetryや儒学Confucianismなど中国文化Chinese cultureの輸入importに貢献contributedした。

In addition, from Gozan,

Zen scriptures, Confucian books, poetry, dictionaries, etc., were actively

published and called the Gozan Edition, which contributed to the import of

Chinese culture such as Chinese poetry and Confucianism.

醍醐寺(だいごじ)Daigo-ji 真言宗(しんごんしゅう)Shingon Buddhism

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City伏見区(ふしみく)Fushimi-ku

鎌倉新仏教の発展

Development of Kamakura

New Buddhism

奈良仏教Nara Buddhism・平安仏教Heian

Buddhismは保護者protectorsであった公家の没落the fall of court nobles、経済的基盤economic foundationであった荘園制の解体the dissolution of the manor system、それに土一揆(どいっき)Do Ikki(uprising)と戦乱warによって衰えてdeclinedいった。

Nara Buddhism and Heian

Buddhism declined due to the fall of court nobles who were their protectors,

the dissolution of the manor system that was their economic foundation, and the

tsuchi ikki and war.

室町期Muromachi

periodの旧仏教系僧侶former Buddhist monksの活躍では、満済(まんさい)Mansaiと真盛(しんぜい)Shinzeiが注目される程度である。

Among the activities of

former Buddhist monks in the Muromachi period, only Mansai and Shinsei have

been noted.

満済(まんさい)Mansai 真言宗(しんごんしゅう)Shingon Buddhism

満済(まんさい)Mansaiは真言宗(しんごんしゅう)Shingon Buddhism醍醐寺(だいごじ)Daigo-jiの僧monkで、足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuの帰依(きえ)Refuge in Buddhismを得て幕政the shogunate governmentにも参画participatedし権勢を振るったwielded power。

Mansai was a monk at

Daigoji Temple of the Shingon sect, and with the faith of Yoshimitsu Ashikaga, he

participated in the shogunate government and wielded power.

『満済准后日記(まんさい・じゅごう・にっき)Mansai Jugo Nikki』は、室町時代初期the early Muromachi periodの重要importantな政治史料political historical materialである。

"Mansai Jugo

Nikki" is an important political historical material in the early

Muromachi period.

真盛(しんぜい)Shinzei 天台宗(てんだいしゅう)Tendai School

真盛(しんぜい)Shinzeiは天台宗(てんだいしゅう)Tendai Schoolの僧monkで、天台(てんだい)Tiantaiの戒律the preceptsに念仏(ねんぶつ)Nembutsuを加え、応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warの頃、京都(きょうと)Kyotoで布教spread the teachingsして公家court nobles・武家samurai families・庶民ordinary peopleに帰依者devoteesを得て天台宗(てんだいしゅう)Tendai Schoolの庶民化popularizeに努めた。

Shinsei was a monk of the

Tendai sect who added nenbutsu (Buddhist invocation) to the precepts of the

Tendai sect, and around the time of the Onin War, he spread the teachings in

Kyoto, gaining devotees among court nobles, samurai families, and ordinary people,

and worked to popularize the Tendai sect.

法然(ほうねん)Hōnen

浄土宗(じょうどしゅう)Jōdo-shū(The Pure Land School)

一遍(いっぺん)Ippen(智真(ちしん)Chishin)(1239~1289)

時宗(じしゅう)Ji-shū(時衆)

代わって発展developedしたのは鎌倉新仏教Kamakura New Buddhism各派the schoolsであった。

Instead, the schools of

Kamakura New Buddhism developed.

例えば浄土宗(じょうどしゅう)Jōdo-shū(The Pure Land School)は、朝廷the

Imperial Courtとの結びつきを強めながら京都(きょうと)Kyotoのほか九州(きゅうしゅう)Kyushu regionや関東(かんとう)Kantō regionで教線を伸ばしextended its teaching、また時宗(じしゅう)Ji-shūはこの時代に大いに盛んで、動乱の時代を戦うfighting in the turbulent times武士層the samurai classに受け入れられgaining acceptance、また芸能者the performing artsのなかに浸透permeateしていく傾向tendingが目立った。

For example, the Jodo

sect of Buddhism, while strengthening its ties with the Imperial Court,

extended its teaching in Kyushu and the Kanto region in addition to Kyoto,

while the Jishu sect was very popular during this period, gaining acceptance

among the samurai class who were fighting in the turbulent times, and tending

to permeate the performing arts.

親鸞(しんらん)Shinran(1173~1262)

浄土真宗(じょうど・しんしゅう)Jōdo Shinshū(The True Essence of the Pure Land Teaching)

覚如(かくにょ)Kakunyo(1270~1351)

本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-ji 西本願寺(にしほんがんじ)Nishi Hongan-ji

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City下京区(しもぎょうく)Shimogyō-ku

浄土真宗(じょうど・しんしゅう)Jōdo Shinshū(The True Essence of the Pure Land Teaching)(真宗(しんしゅう)Shinshū)(一向宗(いっこうしゅう)Ikkō-shū(single-minded school))は、覚如(かくにょ)Kakunyo(1270~1351)の頃親鸞(しんらん)Shinranの廟所(びょうしょ)mausoleumをもとにして京都(きょうと)Kyotoの大谷(おおたに)Otaniに本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiが創建foundedされたが、専修寺派(せんじゅじは)Senju-ji school(三重県専修寺)・仏光寺派(ぶっこうじは)Bukkō-ji school(京都府仏光寺)など各派が分立separatedして室町前期the early Muromachi periodまでは宗勢the religious powerは微力weakであった。

The Jodo Shinshu sect

(Ikko sect) founded Hongan-ji Temple in Otani, Kyoto, based on Shinran's

mausoleum around the time of Kakunyo (1270-1351). Shuji) and the Bukkoji school

(Bukkoji, Kyoto Prefecture) were separated, and until the early Muromachi

period, the religious power was weak.

蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyo(1415~1499)

しかし応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warの頃、本願寺派(ほんがんじは)Hongwanji-haに蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyo(1415~1499)が出て盛んに親鸞(しんらん)Shinranの尊崇reverenceを説いてpreached自派の権威を高めraising the

authority of his sect、多数の「御文(おふみ)Ofumi」(御文章(ごぶんしょう)Gobunsho)を書いて信仰の核心the core of his faithを平易な言葉plain languageで伝えconvey、北陸(ほくりく)Hokuriku region・東海(とうかい)Tōkai region・畿内(きない)Capital Regionで精力的に布教actively preachingし、各地various placesで惣村(そうそん)Sosonを門徒化became a discipleしたので宗勢the religious powerが急に伸びたgrew rapidly。

However, around the time

of the Onin War, Rennyo (1415-1499) appeared in the Hongan-ji sect, and he

actively preached the reverence of Shinran, raising the authority of his sect.

Soson became a disciple, and the sect's power grew rapidly.

He wrote many 'Ofumi'

(Gobunsho) to convey the core of his faith in plain language, actively

preaching in the Hokuriku, Tokai, and Kinai regions, and sent out sosons in

various places. ) became a follower, so the sect's power grew rapidly.

石山本願寺(いしやま・ほんがんじ)Ishiyama

Hongan-ji

蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyo(1415~1499)

真宗門徒the followers

of the Shinshuには農民farmersや商工人merchants and industrialistsや国人(こくじん)Kokujinが多く、蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyoが建てた越前(えちぜん)Echizen Province(福井県(ふくいけん)Fukui Prefecture)の吉崎御坊(よしざき・ごぼう)Yoshizaki-gobō、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの山科本願寺(やましな・ほんがんじ)Yamashina Hongan-ji、大坂(おおさか)Osakaの石山御坊(いしやま・ごぼう)Ishiyama Gobo(のち石山本願寺(いしやま・ほんがんじ)Ishiyama Hongan-ji)は、その地方の門徒の中心the centers of followers in each regionとなって栄えた。

Many of the followers of

the Shinshu sect were farmers, merchants, and industrialists, and the Yoshizaki

Gobo in Echizen, built by Rennyo, the Yamashina Hongan-ji Temple in Kyoto, and

the Ishiyama Gobo (later Ishiyama Hongan-ji Temple) in Osaka, flourished as the

centers of followers in each region.

地方の末寺the branch temples

in the provincesには、坊主(ぼうず)the priestsを中心に門徒the followersによる組(くみ)Kumi・講(こう)Koが組織organizedされ、戦国時代(せんごく・じだい)Sengoku

period(Warring

States period)にかけて各地various

placesで一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)を起こしたcaused。

At the branch temples in

the provinces, Kumi and Ko were organized by the followers, centering on the

priests, and they caused ikko ikki in various places until the Sengoku period.

蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyo(1415~1499)

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin War直前、京都(きょうと)Kyoto大谷(おおたに)Otaniの本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiが比叡山(ひえいざん)Mount Hiei山徒mountaineersに焼き討ちset on

fireされると、蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyoは地方布教missionary missionに旅立った。

Just before the Onin War,

Hongan-ji Temple in Otani, Kyoto was set on fire by mountaineers on Mt. Hiei.

Rennyo set off on a

missionary mission.

近江(おうみ)Omi Province(滋賀県Shiga Prefecture)から北陸(ほくりく)Hokuriku regionに向かい、越前(えちぜん)Echizen Province(福井県(ふくいけん)Fukui Prefecture)の吉崎御坊(よしざき・ごぼう)Yoshizaki-gobōに留まり北陸一帯throughout the Hokuriku regionに布教preachingし、さらに足跡footprintsは東海(とうかい)Tōkai region・畿内(きない)Capital Region・紀伊(きい)Kii Province(和歌山県Wakayama Prefecture、三重県Mie Prefecture)に及んだ。

From Omi, he headed for

Hokuriku, staying at Yoshizaki Gobo in Echizen and preaching throughout the

Hokuriku region, and his footprints extended to the Tokai, Kinai, and Kii

regions.

この布教propagationによって、本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiは諸国農村farming villages around the countryに基盤を置くbased全国的規模の教団nationwide religious organizationとなり、各地various

placesで一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)さえ起こるようになった。

As a result of this

propagation, Hongan-ji Temple became a nationwide religious organization based in

farming villages around the country, and even ikko ikki began to occur in

various places.

山科本願寺(やましな・ほんがんじ)Yamashina

Hongan-ji

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin War後、帰洛returned

to Kyotoした彼は、山科本願寺(やましな・ほんがんじ)Yamashina Hongan-jiを建立builtした。

After the Onin War, he

returned to Kyoto and built Yamashina Hongan-ji Temple.

寺内町(じないまち)temple townができ、諸国all

over the countryから群衆crowds of peopleが参詣visited the templeしてきて大変な賑わいgreat bustleを示した。

A temple town was

established, and crowds of people from all over the country visited the temple,

showing great bustle.

蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyoが念仏(ねんぶつ)Nembutsuについて書き残した消息newsは、農民farmers・国人(こくじん)localsに理解understandできるよう仮名文の平易な文章simple sentences in kanaで記され、のち御文(おふみ)Ofumi(御文章(ごぶんしょう)Gobunsho)としてまとめられた。

The news that Rennyo left

behind regarding Nenbutsu was written in simple sentences in kana so that

farmers and locals could understand it, and later compiled it as Ofumi

(Gobunsho).

専修寺(せんじゅじ)Senju-ji

専修寺(せんじゅじ)Senju-ji

下野国(しもつけのくに)Shimotsuke

Province高田(たかだ)(栃木県Tochigi Prefecture芳賀郡二宮町高田)の親鸞(しんらん)Shinranの遺跡ruinsに、門弟disciple真仏(しんぶつ)Shinbutsuが建てた真宗高田派(しんしゅう・たかだは)Takada school of Shinshu Buddhismの本山(ほんざん)head temple。

The head temple of the

Takada school of Shinshu Buddhism built by Shinbutsu, a disciple of Shinran, in

the ruins of Shinran in Takada, Shimotsuke-no-kuni (Takada, Ninomiya-cho,

Haga-gun, Tochigi Prefecture).

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin War直前の頃、真慧(しんね)Shinneによって伊勢(いせ)Ise Province一身田(いしんでん)Isshinden(三重県(みえけん)Mie Prefecture津市(つし)Tsu City)に移建され、本願寺派(ほんがんじは)Hongwanji-haと対抗した。

Just before the Onin War,

Shinne moved the temple to Ise-Isshinden (Tsu City, Mie Prefecture) to compete

with the Hongan-ji sect.

一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)

一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki

守護大名(しゅご・だいみょう)Shugo-daimyōあるいは戦国大名(せんごく・だいみょう)Sengoku-Daimyōが強力more powerfulになってくると、その支配ruleに対して、一向宗(いっこうしゅう)Ikkō-shū(single-minded school)(浄土真宗(じょうど・しんしゅう)Jōdo Shinshū(The True Essence of the

Pure Land Teaching))の勢力の強い地域では、本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiの末寺the branch templesの坊主(ぼうず)the monksや国人(こくじん)Kokujin・農民門徒peasant followersが団結unitedして抵抗し、また一揆(いっき)Ikki(Uprising)を起こしてこれと戦った。

When the Shugo daimyo or

Sengoku daimyo became more powerful, in areas where the Ikko sect (Jodo Shinshu

sect) was strong, the monks of the branch temples of Hongan-ji Temple, Kokujin,

and peasant followers united to fight against their rule.

信心faithのための組(くみ)Kumiや講(こう)Koが、一揆(いっき)Ikki(Uprising)の時はそのまま一揆(いっき)Ikki(Uprising)の組織organizationとなり、信仰の裏付けbecause of their faithで団結心sense of unityも強く死を恐れなかったdid not fear deathので、一揆(いっき)Ikki(Uprising)の力powerは特に強かった。

The kumi and ko for faith

became the organization of the uprising, and the power of the uprising was

particularly strong because they had a strong sense of unity and did not fear

death because of their faith.

これを一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)と言うが、一揆(いっき)Ikki(Uprising)と大名(だいみょう)Daimyoの戦いbattleは、農村の支配control of farming villagesをめぐる戦いbattleであった。

This is called Ikko Ikki,

and the battle between the ikko ikki and the daimyo was a battle for control of

farming villages.

富樫政親(とがし・まさちか)Togashi

Masachika(1455~1488)

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warの頃、本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiの蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyoが盛んに北陸(ほくりく)Hokuriku regionで布教propagated his religionし宗勢the religious powerを飛躍的に発展rapidly developedさせたため、大規模な一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)ははじめ北陸(ほくりく)Hokuriku regionで起こった。

Around the time of the Onin

War, Rennyo of Hongan-ji Temple actively propagated his religion in the

Hokuriku region and rapidly developed the sect.

特に加賀の一向一揆(かがの・いっこう・いっき)Kaga Rebellionは、1488年(長享2年)に守護(しゅご)Shugoの富樫政親(とがし・まさちか)Togashi Masachika(1455~1488)を敗死killedさせ、以後1世紀余り、加賀国(かがの・くに)Kaga Province(石川県(いしかわけん)Ishikawa

Prefecture南部)は名目的な守護(しゅご)Shugoはいたが実態は本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-jiの領国territoryのようになり、「百姓ノ持チタル国Province of peasants」と評せられて一向宗(いっこうしゅう)Ikkō-shū(single-minded school)門徒the

followers・坊主(ぼうず)the monksによる自治支配governed autonomouslyが行われた。

In 1488, the Kaga Ikko

Ikki in particular killed the shugo, Togashi Masachika (1455-1488), and for

more than a century after that, Kaga Province had a nominal shugo, but in

reality it became like the territory of Hongan-ji Temple. Regarded as a

country, it was governed autonomously by the followers of the Ikko sect, the

monks.

一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)

一向一揆(いっこういっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)はその後、北陸一帯throughout the Hokuriku region・畿内(きない)Capital Region・三河(みかわ)Mikawa Province(愛知県(あいちけん)Aichi Prefecture東半部)・尾張(おわり)Owari Province(愛知県(あいちけん)Aichi Prefecture西部)・紀伊(きい)Kii Province(和歌山県Wakayama

Prefecture、三重県Mie Prefecture)などの諸国でも起こり、守護大名(しゅご・だいみょう)Shugo-daimyōや戦国大名(せんごく・だいみょう)Sengoku-Daimyōと戦った。

After that, Ikko Ikki

occurred in the Hokuriku region, Kinai, Mikawa, Owari, Kii, and other countries,

and fought against Shugo Daimyo and Sengoku Daimyo.

蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyoの頃の一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)は、蓮如(れんにょ)Rennyo自身が教団の平和的発展develop peacefullyを望んでむしろ門徒の一揆を押さえようとしたtried to suppress the uprising of his followersが、戦国時代(せんごくじだい)Sengoku period(Warring

States period)の1532年(天文1年)からは、本願寺(ほんがんじ)Hongan-ji法主(ほっす)the head priest(住職のこと)が指令して蜂起させるordered the rebellion to riseようになり、それだけ規模the scale of the uprisingも強大となり、各地で戦国大名(せんごく・だいみょう)Sengoku-Daimyōと激しく衝突violently collidedした。

In the Ikko Ikki around

the time of Rennyo, Rennyo himself wanted the sect to develop peacefully and

rather tried to suppress the uprising of his followers, but from 1532 (Tenbun 1)

during the Warring States period, the head priest of Hongan-ji Temple ordered

the rebellion to rise, and the scale of the uprising grew to that extent, and

Sengoku daimyo (feudal lords) spread throughout the country. ) and violently

collided.

石山本願寺一揆(いしやま・ほんがんじ・いっき)

1563年(永禄6年)の三河一向一揆(みかわ・いっこう・いっき)Mikawa Ikko Ikkiは、徳川家康(とくがわ・いえやす)Tokugawa Ieyasuを一時は危機に陥れるplunge into crisisほどであった。

The Mikawa Ikko Ikki in

1563 (Eiroku 6) was enough to plunge Ieyasu Tokugawa into crisis for a time.

また織田信長(おだ・のぶなが)Oda Nobunagaの全国統一unified the countryに当たって、1570年(元亀1年)から石山本願寺一揆(いしやま・ほんがんじ・いっき)Ishiyama Hongan-ji Ikkiが諸国various provincesで激しく抵抗violently resistedしたが、1580年(天正8年)に織田信長(おだ・のぶなが)Oda Nobunagaの前に屈服surrenderedし、以後一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)は姿を消したdisappeared。

In addition, when Oda

Nobunaga unified the country, the Ishiyama Hongan-ji Ikki violently resisted in

various provinces from 1570 (Genki 1), but in 1580 (Tensho 8), he surrendered

to Nobunaga Oda, and the Ikko Ikki disappeared after that.

日蓮(にちれん)Nichiren(1222~1282)

日蓮宗(にちれんしゅう)Nichiren-shū(法華宗(ほっけしゅう)Hokke-shū)

日像(にちぞう)Nichizō(1269~1342)

妙顕寺(みょうけんじ)Myoken-ji

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City上京区(かみぎょうく)Kamigyō-ku

鎌倉時代の末the end of

the Kamakura period、日蓮(にちれん)Nichirenの弟子disciple日像(にちぞう)Nichizō(1269~1342)は初めて京都(きょうと)Kyotoで日蓮(にちれん)Nichirenの教えteachingsを広めたspread。

At the end of the Kamakura

period, Nichiren's disciple Nichizo (1269-1342) first spread Nichiren's

teachings in Kyoto.

教義doctrineが商人merchants・職人craftsmenの活動activitiesを肯定affirmsすることから、多くの町衆信者townspeople

believersを得て新興勢力a new powerを形成formedした。

Since the doctrine

affirms the activities of merchants and craftsmen, it gained many townspeople

believers and formed a new power.

諸宗various sectsの圧迫pressureで三度three

times洛中(らくちゅう)Rakuchuを追放expelledされたが、妙顕寺(みょうけんじ)Myoken-jiの開山(かいさん)Kaisan(創立者founder)となった。

He was expelled from

Rakuchu three times under pressure from various sects, but became the founder

of Myoken-ji Temple.

足利義教(あしかが・よしのり)Ashikaga Yoshinori(在職1429~1441)

室町幕府(むろまちばくふ)Muromachi

shogunate第六代征夷大将軍(せいいたいしょうぐん)the sixth Sei-i Taishōgun

日親(にっしん)Nisshin(1407~1488)

また1440年に日親(にっしん)Nisshin(1407~1488)は『立正治国論(りっしょう・ちこくろん)Rissho Chikoku Ron』を著して第六代将軍the sixth Shogun足利義教(あしかが・よしのり)Ashikaga Yoshinoriに諫言(かんげん)admonishedし、投獄imprisoned・拷問torturedを受けたが屈しなかった。

In 1440, Nisshin

(1407-1488) wrote "Rissho Chikoku Ron" (Rissho Chikoku Ron) and

admonished the 6th Shogun Ashikaga Yoshinori.

He admonished Yoshinori

ASHIKAGA and was imprisoned and tortured, but he did not give in.

本法寺(ほんぽうじ)Honpō-ji

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City上京区(かみぎょうく)Kamigyō-ku

京都(きょうと)Kyoto本法寺(ほんぽうじ)Honpō-jiをはじめ30余寺more than 30 templesを開創(かいそう)foundedし、折伏(しゃくぶく)Shakubuku(break and subdue)の伝道(でんどう)preachedを京都(きょうと)Kyoto・九州Kyushu・中国Chugoku・畿内(きない)Capital Region・東海Tokai・関東Kantoで行った。

He founded more than 30

temples, including Kyoto Honpo-ji Temple, and preached shakubuku in Kyoto,

Kyushu, Chugoku, Kinai, Tokai, and Kanto.

こうして、戦国時代(せんごく・じだい)Sengoku period(Warring

States period)の京都(きょうと)Kyotoは「題目(だいもく)Daimoku(南無妙法蓮華経(なむ・みょうほう・れんげ・きょう)Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō(法華経の教えに帰依をするtake refuge in the teachings of the Lotus Sutra))の巷(ちまた)the

streets」と言われるようになり、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの町衆信徒the believers of the townspeopleによる法華一揆(ほっけ・いっき)Hokke Ikkiが起こるようになった。

Thus, during the Sengoku

period, Kyoto came to be called 'Daimoku' (the streets of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo),

and the Hokke-Ikki (Hokkaido uprising) began to occur among the believers of

the townspeople of Kyoto.

日親(にっしん)Nisshin(1407~1488)

日親(にっしん)Nisshin

彼の生涯lifeは、ほとんど伝道の旅missionary journeysに明け暮れた。

Most of his life was

devoted to missionary journeys.

京都(きょうと)Kyotoを中心に東in the

eastは房総(ぼうそう)Bōsō・奥羽(おうう)Ou(東北地方(とうほくちほう)Tōhoku region)まで、西in the westは山陽道(さんようどう)Sanyodo・山陰道(さんいんどう)Sanindoを通って肥前(ひぜん)Hizen

Province(佐賀県(さがけん)Saga Prefecture、長崎県Nagasaki

Prefecture)まで、このルートを何度となく往復made many round trips on this routeして、各地various

placesに合計数十の寺を建てたbuilt a total of dozens of temples。

From Kyoto to Boso and Ou

in the east, to Hizen via Sanyo-do and Sanin-do in the west, he made many round

trips on this route and built a total of dozens of temples in various places.

しかもその伝道evangelismは、他宗other sectsと宗論(しゅうろん)arguingし折伏(しゃくぶく)Shakubuku(break and subdue)するという戦闘的combativeなものであった。

Moreover, the evangelism

was combative, arguing with other sects and shakubuku.

また日親(にっしん)Nisshin(1407~1488)は幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateに対し、日蓮宗(にちれんしゅう)Nichiren-shū(法華宗(ほっけしゅう)Hokke-shū)に改宗(かいしゅう)Religious conversionするよう度々意見書written opinionsを出した。

In addition, Nisshin

frequently submitted written opinions to the bakufu asking them to convert to

the Nichiren sect (the Hokke sect).

その意見書opinionsの一つが『立正治国論(りっしょう・ちこく・ろん)Rissho Chikoku Ron』である。

One of his opinions is

"Risshochikokuron".

「鍋かむりの日親(にっしん)Nabekamuri's Nisshin」

幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateは日親(にっしん)Nisshinを獄に投じimprisoned、逆に改宗(かいしゅう)Religious conversionを迫り拷問torturedを加えたが、日親(にっしん)Nisshinは屈せず題目(だいもく)Daimoku(南無妙法蓮華経(なむ・みょうほう・れんげ・きょう)Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō(法華経の教えに帰依をするtake refuge in the teachings of the Lotus Sutra))を唱えた。

The shogunate imprisoned

Nisshin and forced him to convert and tortured him.

さらに打つ、蹴る、次いで耳を切り鼻をそぎ、口から水を注ぎ込み、舌を切り、最後には真赤に焼いた鍋(なべ)a red-hot panを顔にかぶせたが、それでも日親(にっしん)Nisshinは屈しなかった。

He was beaten, kicked,

then cut off his ears, shaved his nose, poured water into his mouth, cut his

tongue, and finally covered his face with a red-hot pan, but Nisshin did not

give in.

幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateも不気味に感じて釈放したが、日親(にっしん)Nisshinの容貌は二目と見られず、言葉は赤子のように意味不明であったが、人々は彼を権力に抵抗した英雄として「鍋かむりの日親(にっしん)Nabekamuri's

Nisshin」と呼んだ。

The shogunate also felt

eerie and released him, but Nisshin's appearance could not be overlooked, and

his words were as incomprehensible as a baby's, but people called him

'Nabekamuri's Nisshin' as a hero who resisted power.

法華一揆(ほっけ・いっき)Hokke Ikki

京都(きょうと)Kyotoの町衆信徒The

townsfolk believersは、日蓮宗(にちれんしゅう)Nichiren-shū(法華宗(ほっけしゅう)Hokke-shū)の寺院templesや僧侶priestsの指導guidanceのもと、1532年(天文1年)から京都(きょうと)Kyotoを襲撃attackedしてくる土一揆(ど・いっき)Do Ikki(uprising)や一向一揆(いっこう・いっき)Ikkō-ikki(Ikkō-shū Uprising)に対して、彼らの町townsや生活livesをその戦禍the

ravages of warから自衛protectするため、団結して戦ったunited and fought。

The townsfolk believers

in Kyoto, under the guidance of the temples and priests of the Nichiren sect

(Hokkake sect), united and fought against the Doikki and Ikko Ikki attacks that

attacked Kyoto from 1532 (Tenbun 1) in order to protect their towns and lives

from the ravages of war.

これを法華一揆(ほっけ・いっき)Hokke Ikkiと言う。

This is called Hokke Ikki.

土一揆(ど・いっき)Do Ikki(uprising)は、寺社temples and shrines・土倉(どそう)(どくら)warehouses・酒屋(さかや)liquor storesを主な襲撃目標main targetsとしたが、放火arsonや略奪lootingに伴う一般町衆General townspeopleの被害は大きくgreat damage、しかも幕府(ばくふ)Shogunateの権威authorityは失墜し侍所(さむらいどころ)Samurai-dokoro(Board

of Retainers)も有名無実namelessであったから、町衆townspeopleは自らの武力でwith their own armed forces自衛defended themselvesした。

The main targets of the

tsuchi ikki were temples and shrines, warehouses, and liquor stores.

General townspeople

suffered great damage from arson and looting, and the authority of the

shogunate had been lost, and samuraidokoro (samurai dokoro) were nameless.

The townspeople defended

themselves with their own armed forces.

天文法華の乱(てんもん・ほっけ・の・らん)Tenmon Hokke no

Ran

しかし1536年(天文5年)、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの日蓮宗(にちれんしゅう)Nichiren-shūは比叡山(ひえいざん)Mount Hieiと衝突collided withし、比叡山(ひえいざん)Mount Hieiに味方sided withした近江(おうみ)Omi Province(滋賀県Shiga Prefecture)の六角氏(ろっかくし)the Rokkaku clanの軍勢the forcesなどのため、市中in the cityの日蓮宗(にちれんしゅう)Nichiren-shūの寺院すべてall the templesが焼き払われburned down(天文法華の乱(てんもん・ほっけ・の・らん)Tenmon Hokke no Ran)、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの法華一揆(ほっけ・いっき)Hokke Ikkiは消滅extinguishedした。

However, in 1536, the

Nichiren sect of Kyoto collided with Mt. Hiei, and all the temples of the

Nichiren sect in the city were burned down (Tenmon Hokkenoran) due to the

forces of the Rokkaku clan of Omi, who sided with Mt.

The Hokke Ikki in Kyoto

was extinguished.

七福神(しちふくじん)Seven Lucky

Gods

七福神(しちふくじん)Seven Lucky

Gods

民間信仰と神道Folk Religion

and Shinto

商業の発展the development

of commerceにつれて、現世利益(げんぜ・りやく)worldly benefitsを求める七福神信仰(しちふくじん・しんこう)the belief in the Seven Lucky Gods(夷(えびす)Ebisu・大黒(だいこく)Daikoku・毘沙門(びしゃもん)Bishamonなど)が民間among the peopleに大いに流行became very popularした。

Along with the development

of commerce, the belief in the Seven Lucky Gods (Ebisu, Daikoku, Bishamon,

etc.), which seeks worldly benefits, became very popular among the people.

また伊勢神宮(いせ・じんぐう)The Grand Shrine of Ise(三重県Mie Prefecture)や熊野(くまの)Kumano Region(和歌山県Wakayama Prefecture、三重県Mie Prefecture)では、御師(おし)Oshiの活躍the activitiesが目立ちconspicuous、彼らは郷村(ごうそん)Gosonに入って伊勢信仰(いせ・しんこう)the Ise beliefや熊野信仰(くまの・しんこう)the Kumano beliefを広め、伊勢詣(いせ・もうで)pilgrimage to Ise・熊野詣(くまの・もうで)pilgrimage to Kumanoの庶民the common peopleの先達(せんだつ)guidesをつとめた。

Also, at Ise Jingu and

Kumano, the activities of the Oshi became conspicuous.

They entered their home

villages and spread the Ise and Kumano beliefs, and served as guides for the

common people to make pilgrimages to Ise and Kumano.

また旧仏教(きゅう・ぶっきょう)Old Buddhismの寺院Buddhist templeは、経済基盤economic baseの荘園the manorsが崩壊collapsedしたので庶民the common peopleに接近approachせざるを得ず、それぞれ霊験(れいげん)miraculous experiencesを喧伝(けんでん)Propagandaし、庶民the common peopleのなかに観音霊場(かんのん・れいじょう)Kannon Sacred Sitesなど寺院巡礼(じいん・じゅんれい)pilgrimage to templesの風習customを起こした。

In addition, the former

Buddhist temples had no choice but to approach the common people because the

manors that served as their economic base collapsed, and they spread the word

about miraculous experiences among the common people.

Among the common people,

he started the custom of pilgrimage to temples such as Kannon Sacred Sites.

御師(おし)Oshi

御師(おし)Oshiとは、大社(たいしゃ)large shrines・大寺(だいじ)large templesの下級神官lower-level Shinto priestsや社僧priests of shrinesのことであるが、信者believersの参詣visitsや祈祷prayersや宿泊lodgingの世話took care ofをし、これら寺社temples and shrinesの庶民化popularizingの先頭を切りtook the lead、伊勢詣(いせ・もうで)visiting Ise・熊野詣(くまの・もうで)visiting Kumanoの風習customを中世庶民社会the common people in the Middle Agesに定着establishedさせた。

It refers to lower-level

Shinto priests and priests of large shrines and temples, who took care of

visits, prayers, and lodging of believers, took the lead in popularizing these

temples and shrines, and established the custom of visiting Ise and Kumano in

the common people in the Middle Ages.

西国三十三所巡礼(さいごく・さんじゅうさんしょ・じゅんれい)Saigoku 33 Pilgrimage

四国八十八カ所巡拝(しこく・はちじゅうはっかしょ・じゅんぱい)Shikoku 88 Sacred Sites Pilgrimage

空海(くうかい)Kukai(弘法大師(こうぼう・だいし)Kobo Daishi)(774~835)

高野詣(こうや・もうで)visit Koya

当時、庶民the common peopleのなかに観音信仰(かんのん・しんこう)Kannon worshipや大師信仰(だいし・しんこう)Daishi worship(弘法大師(こうぼう・だいし)Kobo Daishi)が起こっていた。

At that time, the common

people worshiped Kannon and Daishi (Kobo Daishi).

近畿地方the Kinki

regionなどでは、霊場(れいじょう)Sacred Sitesを巡拝pilgrimage toする風習customがこの時代に盛んとなったbecame popular。

In the Kinki region,

etc., the custom of making a pilgrimage to Kannon's sacred sites became popular

during this period.

これを西国三十三所巡礼(さいごく・さんじゅうさんしょ・じゅんれい)Saigoku 33 Pilgrimageと言う。

This is called Saigoku 33

Pilgrimage (Saigoku 33 Kannon Pilgrimage).

また讃岐(さぬき)Sanuki Province(香川県Kagawa Prefecture)は弘法大師(こうぼう・だいし)Kobo Daishi(空海(くうかい))Kukaiの出生the birthと因縁が深かったdeep connectionので四国48か所 the 48 temples

in Shikokuの弘法大師霊場Kobo Daishi Sacred Sitesと言われる寺院templesが喧伝advertisedされ、それらは遍路(へんろ)Henro(pilgrim)の巡拝pilgrimagesで賑わった(四国八十八カ所巡拝(しこく・はちじゅうはっかしょ・じゅんぱい)Shikoku 88 Sacred Sites Pilgrimage)。

In addition, Sanuki had a

deep connection with the birth of Kobo Daishi (Kukai), so the 48 temples in

Shikoku known as Kobo Daishi Sacred Sites were advertised, and they were

bustling with pilgrimages (Shikoku 88 Sacred Sites Pilgrimage).

紀伊(きい)Kii Province(和歌山県Wakayama

Prefecture、三重県Mie Prefecture)の高野山(こうやさん)Mount Kōyaも弘法大師(こうぼう・だいし)Kobo Daishiの墳墓tombがある霊場sacred siteで、庶民commonersの高野詣(こうや・もうで)visit Koyaや、納骨bury his bonesの風習customsが盛んであった。

Koyasan in the Kii region

is also a sacred site with the tomb of Kobo Daishi, and the customs of

commoners to visit Koya and bury his bones were popular.

吉田兼倶(よしだ・かねとも)Yoshida

Kanetomo(1435~1511)

吉田神道(よしだ・しんとう)Yoshida

Shinto

吉田神社(よしだ・じんじゃ)Yoshida

Shrine

京都市(きょうとし)Kyoto City左京区(さきょうく)Sakyō-ku

応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warの頃、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの吉田神社(よしだ・じんじゃ)Yoshida Shrineの神主the head priest吉田兼倶(よしだ・かねとも)Yoshida Kanetomo(1435~1511)は、反本地垂迹説(はん・ほんじ・すいじゃく・せつ)Anti Honji Suijaku theory(神Shintoismを本basisとし、仏Buddhaを従subordinateとする神仏習合説(しんぶつ・しゅうごう・せつ)Shinbutsu-shugo(Syncretism

of Shinto and Buddhism))を唱え、神道(しんとう)Shintoを中心に儒仏二道(じゅぶつ・にどう)Confucianism and Buddhismを統合integratedした唯一神道(ゆいいつ・しんとう)the only Shintoism(吉田神道(よしだ・しんとう)Yoshida Shinto)を説いた。

Around the time of the

Onin War, Kaneto Yoshida (1435-1511), the head priest of Yoshida Shrine in

Kyoto, advocated the anti-Honji Suijaku theory (a theory that Shintoism is the

basis and Buddha is the subordinate), and established the only Shintoism

(Yoshida-jin) that integrated Confucianism and Buddhism centered on Shinto. He

preached the way (Yoshida Shinto).

田楽(でんがく)Dengaku(Music and dance to pray for a good harvest before rice planting)

芸能の成長Growth of Art

鎌倉末the end of

Kamakuraから室町前期the early Muromachi periodの頃、都市urban areas・農村rural areasを問わず田楽(でんがく)Dengaku(Music and dance to pray

for a good harvest before rice planting)が流行became popularして、全盛期its peakを迎えていた。

From the end of Kamakura

to the early Muromachi period, dengaku became popular in both urban and rural areas,

and reached its peak.

公家court nobles・武士samurai・庶民commonersの別なく、これを愛好lovedし、これを専業とする田楽法師(でんがく・ほうし)Dengaku-hoshiたちは、座(ざ)Za(guilds)を結成formedしていたほどであった。

Dengaku-hoshi, who loved

it and specialized in it, regardless of whether they were court nobles,

samurai, or commoners, even formed a troupe.

田楽(でんがく)Dengaku(Music and dance to pray for a good harvest before rice planting)

田楽(でんがく)Dengaku(Music and dance to pray for a good harvest before rice planting)は、田植rice

plantingなどのとき行われた神事Shinto ritualsから発達developedした芸能performing artで、平安時代Heian periodから広まった。

Dengaku is a performing

art that developed from Shinto rituals that were performed during rice

planting, and spread from the Heian period.

特に、鎌倉末期the end of Kamakuraから南北朝内乱期the Civil War of the Northern and Southern Courtsにかけての流行fashionは、目を見張らせるものがある。

In particular, the

fashion from the end of Kamakura to the Civil War of the Northern and Southern

Courts is something to behold.

北条高時(ほうじょう・たかとき)Hōjō Takatoki(在職1316~1326)

鎌倉幕府(かまくらばくふ)Kamakura shogunate第14代執権(しっけん)the 14th shikken

北条貞時(ほうじょうさだとき)Hōjō Sadatoki(北条時宗(ほうじょうときむね)Hōjō Tokimuneの子son)の三男the Third son

二条河原の落書(にじょう・がわら・の・らくしょ)the graffiti

of Nijogawaraのなかにも、「犬Inu田楽(でんがく)Dengakuハ関東Kanto

regionノ、滅(ほろ)ブル物the ruined toyトイヒナガラ、田楽(でんがく)Dengakuハナホハヤルナリ」と見え、鎌倉幕府滅亡the fall of the Kamakura shogunateの一因one of

the reasonsに、北条高時(ほうじょう・たかとき)Hōjō Takatoki(在職1316~1326)が異常に田楽(でんがく)興行dengaku performancesに熱をあげたことを指摘している。

In the graffiti of

Nijogawara, it can be seen that ``Inu dengaku is in the Kanto region, and the

ruined toy Hinagara, dengaku is hanahayarunari,'' pointing out that one of the

reasons for the fall of the Kamakura shogunate was Hojo Takatoki (1316-1326),

who was unusually enthusiastic about dengaku performances.

当時の田楽(でんがく)Dengakuは、美麗な飾りをつけた田楽法師(でんがく・ほうし)Dengaku-hoshiが囃子(はやし)Hayashi(musical accompaniment)や歌謡songsに合わせて舞うものであったらしく、人々の人気を集めた。

At that time, Dengaku was

a dance performed to the accompaniment of musical accompaniment and songs by a

beautifully decorated dengaku hoshi, and was very popular with the people.

寺社の再興や修理restoring and

repairing temples and shrinesを名目guiseに興行された勧進田楽(かんじん・でんがく)Kanjin dengakuが、都市cities・農村farming villagesで盛んに行われた。

Kanjin dengaku, which was

performed under the guise of restoring and repairing temples and shrines, was

popular in cities and farming villages.

猿楽(さるがく)Sarugaku(monkey music)

大和猿楽四座(やまと・さるがく・しざ)Yamato

Sarugaku Shiza

奈良時代Nara periodに中国Chinaから伝わった散楽(さんがく)Sangakuの系統を引く猿楽(さるがく)Sarugaku(monkey music)は、大和(やまと)Yamato Province(奈良県Nara Prefecture)では興福寺(こうふくじ)Kōfuku-ji・春日社(かすがしゃ)Kasuga-shaに奉仕する大和猿楽四座(やまと・さるがく・しざ)Yamato Sarugaku Shiza(のちに金春座(こんぱるざ)Konparuza・宝生座(ほうしょうざ)Hoshoza・観世座(かんぜざ)Kanzeza・金剛座(こんごうざ)Kongozaに発展)、それに近江猿楽三座(おうみ・さるがく・さんざ)Omi Sarugaku Sanzaの活躍が目立った。

Sarugaku, which is

descended from Sangaku, which was introduced from China in the Nara period, was

prominent in Yamato, where the four Yamato Sarugaku troupes (later developed

into Konparuza, Hoshoza, Kanzeza, and Kongoza) that served Kofuku-ji Temple and

Kasuga Shrine, and the Omi Sarugaku Sanza.

猿楽(さるがく)Sarugaku(monkey music)は次第に整備されて能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)や狂言(きょうげん)Kyōgen(mad words)(wild speech)となった。

Sarugaku gradually

evolved into Noh and Kyogen.

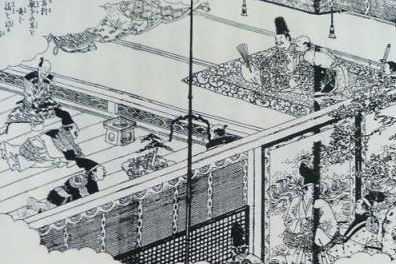

能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)

能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)は謡(うたい)Utai(singing)と囃子(はやし)Hayashi(musical accompaniment)と舞(まい)Mai(dance)からなる総合舞台演劇comprehensive stage playで、南北朝時代the period of the Northern and Southern Courtsまで、田楽の能(でんがく・の・のう)Dengaku Noh・猿楽の能(さるがく・の・のう)Sarugaku Nohの二つの系統のものが、民間芸能folk performing artsとして持て囃されていた。

Noh is a comprehensive

stage play consisting of singing, music, and dance. Until the period of the

Northern and Southern Courts, two types of Noh, Dengaku Noh and Sarugaku Noh,

were performed as folk performing arts.

観阿弥清次(かんあみ・きよつぐ)Kan'ami

Kiyotsugu(1333~1384)

世阿弥元清(ぜあみ・もときよ)Zeami

Motokiyo(1363~1443)

14世紀の末the end of the 14th century、大和猿楽四座(やまと・さるがく・しざ)Yamato Sarugaku Shizaの一つの観世座(かんぜざ)Kanzezaでは観阿弥清次(かんあみ・きよつぐ)Kan'ami Kiyotsugu(1333~1384)・世阿弥元清(ぜあみ・もときよ)Zeami Motokiyo(1363~1443)の父子father and sonが足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuの保護protectionを受けて、幽玄(ゆうげん)Yūgen(趣きが深く、高尚で優美なこと)(Tasteful,

noble and graceful)を旨(むね)emphasizesとする猿楽の能(さるがく・の・のう)Sarugaku Nohを完成perfectedした。

At the end of the 14th

century, at the Kanzeza, one of the four Yamato sarugaku theaters, Kanami

Kiyotsugu (1333-1384) and Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443), father and son, under the

protection of Yoshimitsu Ashikaga, perfected a sarugaku noh play that

emphasizes the subtle and profound.

これ以後、能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)は社寺shrines and templesよりも武士階級the samurai classの保護protectionを得て発展developedすることとなった。

Since then, Noh has

developed under the protection of the samurai class rather than shrines and

temples.

世阿弥(ぜあみ)Zeamiは『風姿花伝(ふうし・かでん)Fūshikaden(Style and the Flower)』(『花伝書(かでんしょ)Kadensho(The Book of Transmission

of the Flower)』)・『申楽談儀(さるがく・だんぎ)Sarugaku Dangi』などによって、能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)の本質essenceを述べた。

Zeami described the

essence of Noh through "Fushi Kaden" ("Kadensho") and

"Sarugaku Dangi".

観阿弥(かんあみ)Kan'ami・世阿弥(ぜあみ)Zeamiは、能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)の脚本scriptsである謡曲(ようきょく)Yōkyoku(謡(うたい)Utai(singing))を多く残した。

Kanami and Zeami left

behind many yokyoku (songs), scripts for Noh plays.

謡曲(ようきょく)Yōkyoku(謡(うたい)Utai(singing))はこの時代を代表する文学作品literary

workでもある。

Yokyoku (chanting) is

also a representative literary work of this era.

金春禅竹(こんぱる・ぜんちく)Konparu

Zenchiku(1405~1468)

金春禅竹(こんぱる・ぜんちく)Konparu

Zenchiku(1405~1468)(世阿弥(ぜあみ)Zeamiの女婿son-in-law)が、世阿弥(ぜあみ)Zeamiから芸the artの相伝を受け、室町中期the mid-Muromachi periodを代表する能(のう)Noh(skill)(talent)の名手a masterとなり、金春座(こんぱるざ)Konparu-zaの地位を不動のものとした。

Konparu Zenchiku

(1405-1468) (Zeami's son-in-law) inherited the art from Zeami and became a

master of Noh, representing the mid-Muromachi period, and established the position

of Konparu-za.

また、町衆townspeopleの間でもしばしば能(のう)Nohが上演されて、能(のう)Nohはこの頃最盛期を迎えた。

In addition, Noh was

often performed among townspeople, and Noh reached its peak around this time.

狂言(きょうげん)Kyōgen(mad words)(wild speech)

狂言(きょうげん)Kyōgen(mad words)(wild speech)は、能(のう)Nohの合間に演じられた滑稽(こっけい)humorと風刺satireを基調とした物真似の喜劇an imitation comedyで、猿楽(さるがく)Sarugaku(monkey music)の持つ滑稽味が洗練されて独立したものindependent formである。

Kyogen is an imitation

comedy based on humor and satire performed between Noh performances, and is a

sophisticated and independent form of sarugaku.

当時の世相the social conditions

of the timeを織り込み、強者への風刺caricaturing the powerfulを題材としたりして、能(のう)Nohよりも通俗的であり、庶民the common peopleに愛好された。

Incorporating the social

conditions of the time and caricaturing the powerful, it was more popular than

Noh and was loved by the common people.

千秋万歳(せんず・まんざい)Senzumanzai

唱門師(しょうもんじ)Shōmonji(声聞師(しょうもんじ)voice listeners)

放下(ほうか)Hoka(放家(ほうか))

傀儡子(くぐつ)Kugutsu

曲舞(くせまい)Kusemai

古浄瑠璃(こじょうるり)Kojoruri

盆踊り(ぼんおどり)Bon Odori

念仏踊り(ねんぶつ・おどり)Nenbutsu

Odori

以上のほか庶民the common peopleの間に、応仁の乱(おうにん・の・らん)Ōnin Warから戦国期the Sengoku periodにかけて、

In addition to the above,

among the common people, from the Onin War (Onin War) to the Sengoku period,

非人身分non-human

backgroundsの出自をもつ遊芸民entertainers・雑芸能民miscellaneous entertainersが、慶事auspicious occasionsの際に繁栄prosperityと長寿longevity祈願の賀詞a prayer forを述べる千秋万歳(せんず・まんざい)Senzumanzai、

Senzumanzai, a prayer for

prosperity and longevity, is said by entertainers and miscellaneous entertainers

from non-human backgrounds on auspicious occasions.

卜占(うらない)uranaiを本業として経読(きょうよみ)sutra recitation・曲舞(くせまい)kusemaiを生業とする唱門師(しょうもんじ)Shōmonji(声聞師(しょうもんじ)voice listeners)、

Shōmonji (voice

listeners), whose main business is uranai, but also sutra recitation and

kusemai,

僧形the form of a

monkをして品玉(しなだま)ball・輪鼓(りゅうご)ring drum・手鞠(てまり)Temariなどを曲取(きょくど)るplays放下(ほうか)Hoka(放家(ほうか))、

Hoka (hoka), who takes

the form of a monk and plays a ball, ring drum, temari, etc.

人形劇puppetryを中心に多様な雑芸a

variety of miscellaneous tricksを合わせて行う傀儡子(くぐつ)Kugutsu、

Kugutsu perform a variety

of miscellaneous tricks centered on puppetry,

白拍子舞(しらびょうし・まい)Shirabyoushimaiから派生した舞(まい)danceを伴う謡(うたい)songで鼓(つづみ)hand drumで伴奏accompaniedする曲舞(くせまい)Kusemaiなどがあった。

There was Kusemai, a song

accompanied by a dance derived from Shirabyoushimai, accompanied by a hand

drum.

また風流踊り(ふりゅう・おどり)Furyu Odori・幸若舞(こうわか・まい)Kōwakamai・古浄瑠璃(こじょうるり)Kojoruri・盆踊り(ぼんおどり)Bon Odori・念仏踊り(ねんぶつ・おどり)Nenbutsu Odori・小歌(こうた)Koutaなども流行した。

Furyu Odori, Kowakamai,

Kojoruri, Bon Odori, Nenbutsu Odori, and Kota were also popular.

『閑吟集(かんぎんしゅう)Kanginshu』(1518年)は小歌(こうた)Koutaの歌集collectionとして有名で、当時の庶民the common peopleの生活思想the lifestyleがよくうかがえる。

"Kanginshu" (1518)

is famous as a collection of short poems, and it gives us a good idea of the

lifestyle of the common people at that time.

風流踊り(ふりゅう・おどり)Furyu Odori

正月the New Yearや盆(ぼん)Bonや祭礼festivalsのときなどに、都市citiesや農村farm

villagesで珍しい意匠unusual designsをこらした飾り物ornamentsなどを着けて踊ったdancedもの。

During the New Year,

Obon, festivals, etc., people danced wearing ornaments with unusual designs in

cities and farm villages.

今日の郷土芸能local performing artsのなかにも伝承されている。

It has been handed down

in today's local performing arts.

桃井直詮(もものい・なおあきら)Momoi Naoakira

幸若舞(こうわか・まい)Kōwakamai

室町初期in the early

Muromachi periodに桃井直詮(もものい・なおあきら)Momoi Naoakira(幼名幸若丸(こうわかまる)Kowakamaru)によって創められたと言う曲舞(くせまい)Kusemaiの一種。

A type of Kusemai that is

said to have been created by Naokira Momoi (childhood name Kowakamaru) in the

early Muromachi period.

軍記物語(ぐんきものがたり)Gunki

monogatariなどを、太鼓(たいこ)Taiko・小鼓(こつづみ)Kotsuzumiに合わせて謡ったsang。

They sang Gunki

Monogatari and other tales to the accompaniment of taiko and kotsuzumi drums.

小歌(こうた)Kouta 小唄(こうた)Kouta

当時、民間the publicでうたわれた俗謡Folk songs・民謡Folk songsのこと。

Folk songs and folk songs

that were sung by the public at the time.

小唄(こうた)Koutaとも言う。

It is also called Kouta.

平安末期the late

Heian periodの雑芸(ぞうげい)Miscellaneous artsや今様(いまよう)Imayō、桃山時代Momoyama periodの隆達節(りゅうたつぶし)Ryutatsubushiなども小歌(こうた)Koutaの部類categoryに入る。

Miscellaneous arts and

imayo from the late Heian period, and ryudatsubushi from the Momoyama period

are also included in the category of kouta.

茶の湯(ちゃのゆ)Chanoyu

茶寄合(ちゃよりあい)Chayoriai

香寄合(こうよりあい)Koyoriai

連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)の寄合(よりあい)Yoriai

寄合(よりあい)の芸能Yoriai entertainmentは南北朝時代the period of the Northern and Southern Courtsに素地が作られ、室町時代Muromachi

periodに入って盛んに行われた。

Yoriai entertainment was

established in the period of the Northern and Southern Courts and became

popular in the Muromachi period.

この寄合(よりあい)Yoriaiは、武将military commanders・一般武士general samurai・僧侶priests・庶民commoners、ときには公家court noblesも加わる集団的な場gathering placeで、共同の楽しみcommunal enjoymentで支えられた。

This yoriai was a

gathering place in which military commanders, general samurai, priests, commoners,

and sometimes court nobles participated, and was supported by communal enjoyment.

禅宗(ぜんしゅう)Zen Buddhismの寺templesで前代から行われた喫茶(きっさ)drinking teaの風習customが、茶の湯(ちゃのゆ)Chanoyuとして一般に広まり、茶寄合(ちゃよりあい)Chayoriaiと呼ばれる茶会(ちゃかい)tea gatheringsが流行した。

The custom of drinking

tea, which had been practiced in Zen temples since the previous generation,

spread to the general public as chanoyu, and tea gatherings called chayoriai

became popular.

ここでは集まった人々が飲んだ茶の銘柄を当て、賭(かけ)をする闘茶(とうちゃ)Tōchaが行われた。

Here, people gathered to

guess the brand of tea they drank and bet on it.

香(こう)incenseを炊いてこれを楽しむ香寄合(こうよりあい)Koyoriaiや、連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)の寄合(よりあい)Yoriaiも流行した。

Koyoriai, in which people

enjoy burning incense, and Yoriai, in which linked poems are played, became

popular.

これらの寄合(よりあい)Yoriaiには立花(りっか)Rikkaが飾られ、立花(りっか)を生業とする人も現れた。

These gatherings were

decorated with rikka, and some people started making a living from rikka.

村田珠光(むらた・じゅこう)Murata Jukō(1423~1502)

武野紹鴎(たけの・じょうおう)Takeno Jōō(1502~1555)

同仁斎(どうじんさい)Dojinsai

池坊専慶(いけのぼう・せんけい)Ikenobo Senkei

こうして室町中期the middle of the Muromachi periodから戦国期the

Sengoku periodにかけ、茶道(さどう)Sadō(The Way of Tea)・花道(かどう)Kadō(way of flowers)・香道(こうどう)Kōdō(Way of Fragrance)が成立した。

In this way, the tea

ceremony, flower ceremony, and incense ceremony were established from the

middle of the Muromachi period to the Sengoku period.

茶道(さどう)Sadō(The Way of Tea)は足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaの頃村田珠光(むらた・じゅこう)Murata Jukō(1423~1502)が出て禅(ぜん)Zenと茶の精神the spirit of teaの統一unificationを主張し、茶室tea roomで閑寂tranquilityを旨とする侘び茶(わびちゃ)Wabi-chaを創始し、これが武野紹鴎(たけの・じょうおう)Takeno Jōō(1502~1555)ら堺町人に伝わり、やがて安土桃山時代the Azuchi-Momoyama periodに千利休(せん・の・りきゅう)Sen no Rikyūによって完成された。

During the reign of

Yoshimasa Ashikaga, Jyukou Murata (1423-1502) appeared in the tea ceremony,

advocating the unification of Zen and the spirit of tea, and founded wabi-cha,

a style of tea ceremony that emphasizes tranquility in a tea room.

This was passed on to

Takeno Joo and other Sakai townspeople, and was eventually perfected by Sen no

Rikyu during the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaが建てた東求堂(とうぐどう)Togudoの東北隅にある四畳半の同仁斎(どうじんさい)Dojinsaiは、茶室建築tea house architectureの源流と言われる。

Dojinsai, a 4.5 tatami

mat room located in the northeastern corner of Togudo built by Yoshimasa

Ashikaga, is said to be the origin of tea house architecture.

また花道(かどう)Kadō(way of flowers)は、仏殿(ぶつでん)Buddhist templesなどに大がかりで飾る立花(りっか)Rikkaのほか、書院study roomsの床に飾る生花(いけばな)Ikebana(making flowers alive)が発達し、足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaの頃、京都(きょうと)Kyoto六角堂(ろっかくどう)Rokkakudōの池坊専慶(いけのぼう・せんけい)Ikenobo Senkeiや将軍Shogunの同朋衆(どうぼうしゅう)Doboshuに名手mastersが現れた。

As for hanamichi, in

addition to rikka, which is used to decorate Buddhist temples on a grand scale,

ikebana, which is used to decorate the floors of study rooms, has developed.

Around the time of

Yoshimasa ASHIKAGA, masters appeared in Senkei Ikenobo of Rokkakudo in Kyoto

and the Shogun's group.

同朋衆(どうぼうしゅう)Doboshu

善阿弥(ぜんあみ)Zenami

同朋衆(どうぼうしゅう)Doboshu

足利将軍Ashikaga shogunに芸の特技special

skills in performing artsをもって近侍close attendantし、立花(りっか)Rikka・芸能performing arts・唐物(からもの)の鑑定appraisal

of karamonoなど数寄(すき)sukiの道wayに秀でたexcelled人。

He was a close attendant

of the Ashikaga shogun with his special skills in performing arts, and excelled

in the path of suki, such as rikka, performing arts, and appraisal of karamono.

多くは阿弥号(あみごう)the name Amiをつけて「~阿弥(あみ)Ami」と言い、身分は低いrank is low。

Most of them use the name

Ami and call themselves ``Ami'', and their rank is low.

将軍shogun足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaに仕えた河原者(かわらもの)Kawaramono善阿弥(ぜんあみ)Zenamiは作庭家landscape

gardenerで「泉石(せんせき)Sensekiの妙手master」と称えられ、

Kawaramono Zenami, who

served the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, was a landscape gardener and was praised

as 'Izumiseki's master'.

唐物(からもの)奉行の能阿弥(のうあみ)Noami・芸阿弥(げいあみ)Geiami・相阿弥(そうあみ)Soamiは茶の湯(ちゃのゆ)Chanoyuの名手mastersで唐物(からもの)鑑定家karamono appraisers、

Noami, Geiami, and Soami,

magistrates of karamono, are masters of the tea ceremony and karamono

appraisers.

文阿弥(ぶんあみ)Bunami・台阿弥(だいあみ)は立花(りっか)Rikkaの名手masters、

Bunami and Daiami are

masters of Rikka,

木阿弥(もくあみ)Mokuami・量阿弥(りょうあみ)Ryoamiは連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)で知られた。

Kiami and Ryoami were

known for their linked poems (renga).

金閣(きんかく)Kinkaku (鹿苑寺(ろくおんじ)Rokuon-ji)

銀閣(ぎんかく)Ginkaku (慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishō-ji)

室町時代の美術Muromachi

period art

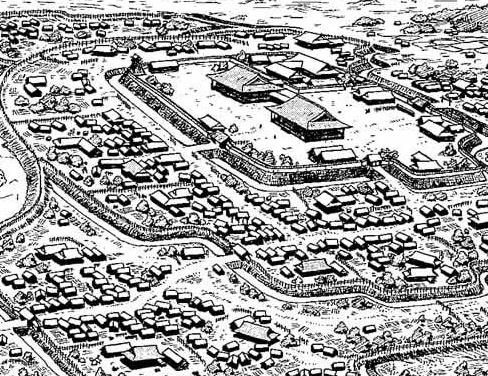

この時代を代表する建築The buildingsは金閣(きんかく)Kinkakuと銀閣(ぎんかく)Ginkakuである。

The buildings that

represent this period are the Kinkaku and Ginkaku.

金閣(きんかく)Kinkaku(鹿苑寺(ろくおんじ)Rokuon-ji)は、足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuが京都(きょうと)Kyoto北山(きたやま)Kitayamaの山荘(さんそう)mountain villaに建てた三層three-storiedの楼閣建築pavilionで、下二層The lower two floorsは寝殿造風(しんでん・づくり)Shindenzukuri style、上層the upper floorが禅宗様(ぜんしゅうよう)Zenshuyo style(唐様(からよう)Karayo style)になっている。

Kinkaku (Rokuonji) is a

three-storied pavilion built by Yoshimitsu Ashikaga in a mountain villa in

Kitayama, Kyoto.

The lower two floors are

Shindenzukuri style, and the upper floor is Zenshuyo style (Karayo style).

銀閣(ぎんかく)Ginkaku(慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishō-ji)は、足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaが東山山荘(ひがしやま・さんそう)Higashiyama mountain villaの内に建てた二層two-storiedの楼閣建築pavilionで、下層The lower layerは書院造(しょいんづくり)風Shoinzukuri

styleで上層the upper layerは禅宗様(ぜんしゅうよう)Zenshuyo(唐様(からよう)Chinese style)である。

Ginkaku (Jishoji Temple)

is a two-storied pavilion built by Yoshimasa Ashikaga inside Higashiyama Sanso.

The lower layer is Shoinzukuri

style, and the upper layer is Zenshuyo (Chinese style).

室町時代の文化The culture

of the Muromachi periodで、特に足利義満(あしかが・よしみつ)Ashikaga Yoshimitsuの時代の文化the cultureを北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama culture、

The culture of the Muromachi

period, especially the culture of Yoshimitsu Ashikaga, is called Kitayama

culture.

また足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaの時代の文化the cultureを東山文化(ひがしやま・ぶんか)Higashiyama cultureと言うが、

Also, the culture of the

time of Yoshimasa Ashikaga is called Higashiyama culture.

金閣(きんかく)Kinkaku・銀閣(ぎんかく)Ginkakuはそれぞれの文化culturesを代表するものである。

Kinkaku and Ginkaku are

representative of their respective cultures.

永保寺(えいほうじ)Eihō-ji開山堂(かいざんどう)Kaizan-do

東福寺(とうふくじ)Tōfuku-ji三門(さんもん)Sanmon(山門)

興福寺(こうふくじ)Kōfuku-ji東金堂(とうこんどう)East Golden Hall

前期には禅宗(ぜんしゅう)Zen Buddhismの興隆に伴い禅宗様(ぜんしゅうよう)Zen sect style(唐様(からよう)Karayo)が発展し、美濃(みの)Mino Province(岐阜県(ぎふけん)Gifu Prefecture南部)永保寺(えいほうじ)Eihō-ji開山堂(かいざんどう)Kaizan-do、京都(きょうと)Kyoto東福寺(とうふくじ)Tōfuku-ji三門(さんもん)Sanmon(山門)が知られる。

In the early period, the

Zen sect style (Karayo) developed with the rise of Zen sect, and the founder of

Eiho-ji Temple in Mino and Sanmon (Sanmon) of Tofukuji Temple in Kyoto are

known.

また和様(わよう)Japanese styleは、興福寺(こうふくじ)Kōfuku-ji東金堂(とうこんどう)East Golden

Hallなどに見られる。

In addition, the Japanese

style can be seen in Kofuku-ji Temple's East Golden Hall.

やがて禅宗様(ぜんしゅうよう)Zen sect style(唐様(からよう)Karayo)と和様(わよう)Japanese styleを折衷した折衷様(せっちゅうよう)eclectic style(新和様(しんわよう)New Japanese style)も発達した。

Before long, an eclectic

style (Shinwa style), which was a blend of Zen style (Karayo) and Japanese style,

also developed.

書院造(しょいんづくり)Shoin-zukuri

住宅建築residential

architectureとしては書院造(しょいんづくり)Shoin-zukuriが室町中期から発達し、僧侶monks・公家court nobles・武士samurai warriors・の住宅the residencesに次第に採用され、今日の和風住宅の源流the origin of today's Japanese-style housesとなった。

Shoin-zukuri style of

residential architecture developed from the mid-Muromachi period, and was

gradually adopted for the residences of monks, court nobles, and samurai

warriors, becoming the origin of today's Japanese-style houses.

その内部は、床(とこ)floor・棚(たな)shelves・書院(しょいん)studyがあり、畳tatami matsが敷かれ、玄関entranceを設け、襖(ふすま)fusuma sliding doorsや障子(しょうじ)shojiを持ち、床(とこ)floorには墨跡(ぼくせき)calligraphyや絵paintingsや生花(いけばな)Ikebana(making flowers alive)による床飾(とこかざり)decorated withが行われた。

The interior has a floor,

shelves, and a study, with tatami mats on the floor, an entrance, fusuma sliding

doors, and shoji screens, and the floor is decorated with calligraphy,

paintings, and fresh flowers.

そのために、絵画paintingや生花(いけばな)Ikebana(making flowers alive)などがいっそう発展した。

For that reason, painting

and flower arrangement (ikebana) developed further.

書院造(しょいんづくり)Shoin-zukuriの遺構としては、足利義政(あしかが・よしまさ)Ashikaga Yoshimasaが東山山荘(ひがしやま・さんそう)Higashiyama mountain villa(現慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishō-ji)に建てた東求堂(とうぐどう)Togudoが有名である。

Togu-do, which was built

by Yoshimasa Ashikaga at Higashiyama Sanso (now Jisho-ji Temple), is famous as

a Shoin-zukuri style ruin.

龍安寺(りょうあんじ)Ryoanji石庭(せきてい)rock gardens

寺院templesや住宅housesには庭園(ていえん)Gardenが発達した。

Gardens developed in temples

and houses.

特に禅宗寺院Zen templesでは、石組(いしぐみ)composed of rocksを主とした枯山水(かれさんすい)karesansuiと呼ばれる枯淡(こたん)simpleな石庭(せきてい)rock gardensが発達し、また武家の住宅では、池水を配した廻遊式庭園strolling gardensが好まれた。

In Zen temples in

particular, simple rock gardens called karesansui, mainly composed of rocks,

developed, and samurai residences favored strolling gardens with ponds.

代表的な庭園(ていえん)Gardenに、西芳寺(さいほうじ)Saihoji(苔寺(こけでら)Kokedera)庭園Garden・天龍寺(てんりゅうじ)Tenryuji庭園Garden・龍安寺(りょうあんじ)Ryoanji石庭(せきてい)rock gardens・大徳寺(だいとくじ)Daitokuji大仙院庭園(だいせんいんていえん)Daisenin

Garden・鹿苑寺(ろくおんじ)Rokuonji庭園Garden・慈照寺(じしょうじ)Jishoji庭園Gardenなどがある。

Typical gardens include

Saihoji (Kokedera) Garden, Tenryuji Garden, Ryoanji Rock Garden, Daitokuji

Daisenin Garden, Rokuonji Garden, and Jishoji Garden.

明兆(みんちょう)Minchō(兆殿司(ちょうでんす)Chodensu)(1352~1431)

瓢鮎図(ひょうねんず)Hyonenzu

雪舟(せっしゅう)Sesshū(1420~1506)

四季山水図(しき・さんすい・ず)Four Seasons

Landscape(山水長巻(さんすい・ちょうかん)Landscape Long Scroll)

大和絵(やまとえ)Yamato-e paintingsや絵巻物(えまきもの)picture scrollsは低調で、代わって、輸入された宋画(そうが)Sung paintings・元画(げんが)Yuan paintings(唐絵(からえ)Karae)の水墨画(すいぼくが)Ink wash paintingが珍重され、その名手も現れた。

Yamato-e paintings and picture

scrolls were sluggish.

Instead, imported Sung

paintings and original paintings (Karae) ink paintings were prized, and some

masters of them appeared.

禅僧Zen priestsの肖像画portraitsである頂相(ちんそう)Chinsōにも見るべきものが残っているが、特に山水水墨画(さんすい・すいぼくが)Sansui suibokugaが禅僧Zen priestsに愛好され発達した。

The chinzo, portraits of

Zen priests, are worthy of note, but Sansui-sui bokuga (landscape ink

paintings) in particular developed with the admiration of Zen priests.

初期には人物people・花鳥birds and flowersを題材にするものが多かったが、のちには山水画(さんすいが)Shan shuiが流行した。

In the early days, people

and birds and flowers were often the subjects, but later Sansuiga became popular.

北山文化(きたやま・ぶんか)Kitayama cultureで明兆(みんちょう)Minchō(兆殿司(ちょうでんす)Chodensu)(1352~1431)・如拙(じょせつ)Josetsu(生没年不詳)(『瓢鮎図(ひょうねんず)Hyonenzu』を描く)・周文(しゅうぶん)Shubun(生没年不詳)が基礎を築き、

Kitayama culture was

founded by Mincho (Chodensu) (1352-1431), Josetsu (years of birth and death

unknown) (painting Hyonensu), and Shubun (years of birth and death unknown).

東山文化(ひがしやま・ぶんか)Higashiyama

cultureを代表する雪舟(せっしゅう)Sesshū(1420~1506)・雪村(せっそん)Sesson(生没年不詳)らによって大成された。

It was completed by

Sesshu (1420-1506) and Sesson (years of birth and death unknown), representatives

of Higashiyama culture.

特に雪舟(せっしゅう)Sesshūは、『四季山水図(しき・さんすい・ず)Four Seasons Landscape(山水長巻(さんすい・ちょうかん)Landscape Long Scroll)』など自然描写nature depictionsに優れ、禅画Zen paintingの域を出て純粋に絵画pure paintingとして独立independentした。

Sesshu, in particular,

excelled in nature depictions such as "Four Seasons Landscape (Landscape

Long Scroll)", leaving the realm of Zen painting and becoming independent

as a pure painting.

いっぽう大和絵(やまとえ)Yamato-e paintingsは、戦国時代the Sengoku periodに土佐光信(とさ・みつのぶ)Tosa Mitsunobu(1469~1525)が出て一時復興されたが、のち衰えた。

On the other hand,

Yamato-e was temporarily revived by Tosa Mitsunobu (1469-1525) during the Sengoku

period, but it declined after that.

土佐光信(とさ・みつのぶ)Tosa Mitsunobu(1469~1525)

土佐光信(とさ・みつのぶ)Tosa Mitsunobuは宮廷imperial

courtの絵所預(えどころ・あずかり)the head of the painting studio(主任のこと)と室町幕府御用the Muromachi shogunate governmentをつとめ、土佐派(とさは)the Tosa schoolの地位を確立した。

Tosa Mitsunobu served as the head of the painting studio at the imperial court

and the Muromachi shogunate government, establishing the position of the Tosa

school.

土佐光信(とさ・みつのぶ)Tosa Mitsunobuの死後、土佐派(とさは)the Tosa schoolは衰えるが、近世初めthe early modern periodに土佐光起(とさ・みつおき)Tosa Mitsuokiが出て復興した。

After the death of Tosa Mitsunobu,

the Tosa faction declined, but in the early modern period, Tosa Mitsuoki came

out and revived.

狩野正信(かのう・まさのぶ)Kano Masanobu(1434~1530)

狩野元信(かのう・もとのぶ)Kano Motonobu(1476~1559)

また狩野正信(かのう・まさのぶ)Kano Masanobu(1434~1530)・狩野元信(かのう・もとのぶ)Kano Motonobu(1476~1559)父子father and sonは、大和絵(やまとえ)Yamato-e paintingsの手法を水墨画(すいぼくが)Ink wash paintingに取り入れ、独特の狩野派(かのうは)Kano schoolの画風を開いた。

Masanobu Kano (1434-1530)

and Motonobu Kano (1476-1559), father and son, incorporated the technique of

Yamato-e into ink painting and created the unique style of Kano school.

能面(のうめん)Noh masks

後藤祐乗(ごとう・ゆうじょう)Goto Yujo(1440~1512)

後藤祐乗(ごとう・ゆうじょう)Goto Yujo(1440~1512)

彫刻sculptureでは、能(のう)Nohの隆盛につれて能面(のうめん)Noh masksの傑作masterpiecesが多く残っている。

As for sculpture, many

masterpieces of Noh masks have survived along with the prosperity of Noh.

工芸craftsでは後藤祐乗(ごとう・ゆうじょう)Goto Yujo(1440~1512)が刀剣金具の金工sword metalworkで名人と言われ、

In crafts, Yujo Goto

(1440-1512) is said to be a master of sword metalwork.

また蒔絵(まきえ)makieに高蒔絵(たかまきえ)takamakie技術が発達するなど、見るべきものが多い。

In addition, there are

many things to see, such as the development of takamakie technique for makie.

高蒔絵(たかまきえ)takamakie

木炭粉Charcoal powderや砥粉abrasive powderを用いて適当な高さに肉上げを施し、その上に蒔絵(まきえ)makieを行ったもの。

Charcoal powder or

abrasive powder is used to raise the thickness to an appropriate height, and

then lacquer work is applied on top of it.

平蒔絵(ひらまきえ)Hiramaki-eに対して言う。

I say this to Hiramaki-e.

この時代に完成し、五十嵐Igarashi・幸阿弥(こうあみ)Koami二家familiesが名を得た。

It was completed during

this period, and the Igarashi and Koami families gained their names.

やがて桃山時代the Momoyama periodには、豪華な高台寺蒔絵(こうだいじ・まきえ)Kodaiji maki-eが現れ、

Eventually, in the

Momoyama period, gorgeous Kodaiji maki-e appeared,

江戸時代the Edo

periodに本阿弥光悦(ほんあみ・こうえつ)Honami Koetsu・尾形光琳(おがた・こうりん)Ogata Korinらによって大成された。

It was perfected by Koetsu

Honami and Korin Ogata in the Edo period.

光厳上皇(こうごん・じょうこう)Retired Emperor Kōgon

光厳天皇(こうごん・てんのう)Emperor Kōgon

北朝(ほくちょう)Northern

Court初代天皇the first Emperor

(在位1331年~1333年)

後伏見天皇(ごふしみ・てんのう)Emperor

Go-Fushimiの第三皇子the Third son

北朝(ほくちょう)Northern

Court(持明院統(じみょういん・とう)Jimyōin-tō)

文芸と学問Literature

and learning

南北朝時代the period of

the Northern and Southern Courtsの和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)はあまり活気が見られず、二条家(にじょうけ)the Nijo family・京極家(きょうごくけ)the Kyogoku familyが対立していた。

Waka poetry in the period

of the Northern and Southern Courts was not very lively, and the Nijo family

and the Kyogoku family were at odds with each other.

勅撰和歌集(ちょくせん・わかしゅう)Chokusen

wakashūでは、京極派(きょうごくは)the Kyogoku schoolに光厳天皇(こうごん)Emperor Kōgon(在位1331~1333)勅撰の『風雅和歌集(ふうが・わかしゅう)Fūga Wakashū』、

Among the chokusenwakashu,

the Kyogoku school, the Emperor Kogon (r.

二条派(にじょうは)The Nijo

schoolに『新千載和歌集(しんせんざい・わかしゅう)Shinsenzai Wakashū』・『新拾遺和歌集(しんしゅうい・わかしゅう)Shinshūi Wakashū』・『新後拾遺和歌集(しんごしゅうい・わかしゅう)Shingoshūi Wakashū』があるが、新鮮さを失っていた。

The Nijo school had

"Shinsenzai Wakashu", "Shinshui Wakashu", and

"Shingoshui Wakashu", but they had lost their freshness.

宗良親王(むねなが・しんのう)Prince Munenaga

このほか、宗良親王(むねなが・しんのう)Prince Munenagaが編集した『新葉和歌集(しんよう・わかしゅう)Shin'yō Wakashū』が南朝方の君臣の歌を集めている。

In addition, "Shinyo

Wakashu" compiled by Imperial Prince Munenaga collects poems by the rulers

and retainers of the Southern Court.

『徒然草(つれづれぐさ)Tsurezuregusa(Essays in Idleness)(The Harvest of Leisure)』

吉田兼好(よしだ・けんこう)Yoshida Kenkō(1283~1350)

今川貞世(いまがわ・さだよ)Imagawa

Sadayo(今川了俊(いまがわ・りょうしゅん)Imagawa Ryōshun)(1326~1420)

歌人the poetsでは、二条派(にじょうは)the Nijo schoolの頓阿(とんあ)Tona(1289~1372)・浄弁(じょうべん)Joben(?~1356)・慶運(けいうん)Keiun・吉田兼好(よしだけんこう)Yoshida Kenkō(1283~1350)が南北朝時代the period of the Northern and Southern Courtsの和歌四天王the Four

Heavenly Kings of Wakaと称され、また二条派(にじょうは)the Nijo schoolを批判した今川貞世(いまがわ・さだよ)Imagawa Sadayo(今川了俊(いまがわ・りょうしゅん)Imagawa Ryōshun)(1326~1420)も注目される歌人noted poetである。

Among the poets of the

Nijo school, Tona (1289-1372), Joben (?-1356), Keiun, and Yoshida Kenko

(1283-1350) were called the Four Heavenly Kings of Waka during the period of

the Northern and Southern Courts, and Imagawa Ryoshun, who criticized the Nijo

school. (Sadayo) is also a noted poet.

勅撰和歌集(ちょくせん・わかしゅう)Chokusen

wakashūは、室町前期the early Muromachi periodの『新続古今和歌集(しんしょく・こきん・わかしゅう)Shinshokukokin Wakashū』を最後に、『古今和歌集(こきん・わかしゅう)Kokin Wakashū』以来の伝統は途絶してしまった。

The chokusenwakashu, which

was compiled by imperial command, ended with the ``Shinshoku Kokinwakashu'' in

the early Muromachi period, and the tradition since the ``Kokinwakashu'' ended.

東常縁(とうの・つねより)Tō no Tsuneyori(1401~1494)

飯尾宗祇(いいお・そうぎ)Iio Sōgi(1421~1502)

しかし、室町時代the Muromachi periodに和歌の聖典the sacred text of waka poetryとされたのは『古今和歌集(こきん・わかしゅう)Kokin Wakashū(Collection of Ancient and

Modern Japanese Poetry)』で、その故実(こじつ)ancient facts解釈interpretationを秘伝口事(ひでんくじ)secret ceremonyで師the masterから弟子the disciplesに授けるteaches、いわゆる古今伝授(こきん・でんじゅ)Kokin Denjuが東常縁(とうの・つねより)Tō no Tsuneyori(1401~1494)によって整えられ、さらにその弟子disciple飯尾宗祇(いいお・そうぎ)Iio Sōgi(1421~1502)によって形式化された。

However, during the

Muromachi period, the "Kokin Wakashu" (Collection of Ancient and Modern

Japanese Poetry) was regarded as the sacred text of waka poetry. 1502).

Tonotsuneyori (1401-1494)

prepared the so-called Kokin Denju, in which the master teaches the disciples

the interpretation of the ancient facts through a secret ceremony. It was

further formalized by his disciple Sogi Iio (1421-1502).

三条西実隆(さんじょうにし・さねたか)Sanjōnishi

Sanetaka(1455~1537)

細川藤孝(ほそかわ・ふじたか)Hosokawa

Fujitaka(幽斎(ゆうさい)Yūsai)(1534~1610)

古今伝授(こきん・でんじゅ)Kokin Denjuはまず東常縁(とうの・つねより)Tō no Tsuneyoriから飯尾宗祇(いいお・そうぎ)Iio Sōgiに伝えられた。

Kokindenju was first

handed down to Sogi by Tonotsuneyori.

飯尾宗祇(いいお・そうぎ)Iio Sōgiから一つは三条西実隆(さんじょうにし・さねたか)Sanjōnishi Sanetaka(1455~1537)を経て細川藤孝(ほそかわ・ふじたか)Hosokawa Fujitaka(幽斎(ゆうさい)Yūsai)(1534~1610)へ(二条伝授Nijo Denju)、

From Sogi, one was

Sanetaka Sanjonishi (1455-1537) and Fujitaka Hosokawa (Yusai) (1534-1610) (Nijo

Denju).

いま一つは宗長(そうちょう)Sochoを経て堺Sakaiの肖柏(しょうはく)Shohakuへ(堺伝授Sakai Denju)、

The other was Socho to

Shohaku in Sakai (Sakai Denju).

さらに奈良Naraの饅頭屋宗二(まんじゅうや・そうじ)Manjuya Soujiに伝授された(奈良伝授Nara Instruction)。

Furthermore, it was

taught by Manjuya Manjuya in Nara (Nara Instruction).

連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)

連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)

和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)は新鮮さを失ったが、南北朝内乱期during the Civil War of the Northern and Southern Courtsの連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)の流行は目覚しかった。

Waka lost its freshness,

but the popularity of renga during the Civil War of the Northern and Southern

Courts was remarkable.

連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)は、和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)を上句(かみのく)upper stanzas・下句(しものく)lower stanzasに分けて詠(よ)み合うものだが、鎌倉時代the Kamakura periodになってから続けて50句・100句と詠(よ)み続ける鎖連歌(くさり・れんが)kusarirengaが盛んとなっていた。

Renga is a form of composing

waka poems by dividing them into upper and lower stanzas, but since the

Kamakura period, kusarirenga, in which 50 verses and 100 verses are continuously

composed, became popular.

そして、公家court nobles・武士samurai・庶民commoners・都市cities・農村farming villagesを問わず流行した。

And it became popular

among court nobles, samurai, commoners, cities, and farming villages.

町衆townspeople・郷村(ごうそん)農民village farmersの成長the growthを背景に連歌(れんが)Renga(linked poem)の庶民化became