日本史43 Japanese history 43

近代文化の形成

Formation of Modern Culture

秋Autumn

久米桂一郎(くめ・けいいちろう)Kume

Keiichiro

班猫(はんびょう)Tabby Cat

竹内栖鳳(たけうち・せいほう)Takeuchi

Seihō

夜汽車(よぎしゃ)Night Train

赤松麟作(あかまつ・りんさく)Akamatsu

Rinsaku

第11章 Chapter 11

近代国家の展開

Development of the Modern

State

第5節 Section 5

近代文化の形成

Formation of Modern Culture

植木枝盛(うえき・えもり)Ueki Emori

中江兆民(なかえ・ちょうみん)Nakae Chōmin

思想Thought

自由民権運動(じゆう・みんけん・うんどう)The Freedom

and People's Rights Movementの発展とともに、運動とのかかわりにおいてその思想ideasや理論theoriesも発達した。

Along with the development

of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, its ideas and theories also

developed in connection with the movement.

大井憲太郎(おおい・けんたろう)Ōi Kentarō

馬場辰猪(ばば・たつい)Baba Tatsui

とくに植木枝盛(うえき・えもり)Ueki Emoriや中江兆民(なかえ・ちょうみん)Nakae Chōminは、代表的な民権思想(みんけん・しそう)the people's rights ideologyの理論家theoristsであり、また大井憲太郎(おおい・けんたろう)Ōi Kentarōや馬場辰猪(ばば・たつい)Baba Tatsuiも、民権運動(みんけん・うんどう)the people's rights movementのみならず当時の有力な理論的指導者theoretical leadersでもあった。

In particular, Emori Ueki

and Chomin Nakae were representative theorists of the people's rights ideology,

and Kentaro Oi and Tatsui Baba were also influential theoretical leaders of the

time, as well as the people's rights movement.

西村茂樹(にしむら・しげき)Nishimura Shigeki

やがて明治10年代の朝鮮問題the

Korean issueを機に、民権論者the people's rights advocatesのなかから国権論(こっけんろん)national rights(民権論に対し、国家の独立・維持を第一義とした思潮)を主張する者が現れた。

Eventually, with the

Korean issue in the Meiji 10s, some advocates of national rights emerged from

among the people's rights advocates.

特に1880年代の後半から、条約改正treaty

revisionsをめぐる政府の欧化政策Europeanization policyを批判criticizingしつつ、民権派the civil rights movementとは別の反政府思想anti-government ideologyとしてのナショナリズムNationalism(自分たち国民、民族を重視するという考え)が台頭emergedした。

Particularly from the

latter half of the 1880s, nationalism emerged as an anti-government ideology

separate from the civil rights movement, criticizing the government's

Europeanization policy regarding treaty revisions.

1884年(明治17年)に西村茂樹(にしむら・しげき)Nishimura Shigekiがおこした日本講道会(にほん・こうどうかい)Japan Kodokai(1887年(明治20年)から日本弘道会)は、伝統的道徳traditional moralityを鼓吹(こすい)promotedしてナショナリズムNationalism(自分たち国民、民族を重視するという考え)の拠点baseとなった。

The Japan Kodokai (Japan

Kodokai from 1887), founded by Shigeki Nishimura in 1884 (Meiji 17), promoted

traditional morality and became a base for nationalism.

三宅雪嶺(みやけ・せつれい)Miyake

Setsurei(雄二郎(ゆうじろう)Yujiro)

志賀重昂(しが・しげたか)Shiga

Shigetaka

その後、1890年代の思想界the

world of thoughtの主要な潮流the main trendとなったのは、三宅雪嶺(みやけ・せつれい)Miyake Setsurei(雄二郎(ゆうじろう)Yujiro)・志賀重昂(しが・しげたか)Shiga Shigetakaらが組織した政教社(せいきょうしゃ)Seikyo-shaの機関紙the official newspaper『日本人(にほんじん)(Nihonjin)Japanese』(1888年(明治21年))に代表される国権主義(こっけん・しゅぎ)National rights(民権論に対し、国家の独立・維持を第一義とした思潮)・国粋主義(こくすい・しゅぎ)Japanese nationalism(日本の文化・伝統の独自性を強調・発揚し、これを保守しようとする政治思想)(国粋保存主義(こくすいほぞん・しゅぎ))。

Afterwards, the main

trend in the world of thought in the 1890s was ``Nihonjin'' (Japanese), the

official newspaper of Seikyo-sha, which was organized by Setsure Miyake

(Yujiro) and Shiga Shigetaka. National rights and nationalism (preservation) as

typified by 1888 (Meiji 21).

『日本人(にほんじん)(Nihonjin)Japanese』

尊王思想(そんのう・しそう)Thought of

reverence for the kingを日本固有の伝統a uniquely Japanese traditionとし、それを中心に国粋保存(こくすいほぞん)preserving national essenceの名の下に国民国家a nation-stateを形成formしようとするもの。

It is an idea that

regards the idea of reverence as a uniquely Japanese tradition, and attempts to

form a nation-state around it in the name of preserving national essence.

陸羯南(くが・かつなん)Kuga Katsunan

政教社(せいきょうしゃ)Seikyo-shaから出て新聞the

newspaper『日本(にっぽん)Nippon』(1889年(明治22年))によった陸羯南(くが・かつなん)Kuga Katsunanらの国民主義(こくみん・しゅぎ)Nationalism(国民の人権や自由を尊重しつつ、民主的に国家を形成・発展させようとする思想・運動)。

The nationalism of Kugakatsunan

and others through the newspaper ``Nippon'' (1889 (Meiji 22)) published by

Seikyo-sha.

政府the

government・民党the Democratic Partyいずれにも同調しない立憲政治constitutional governmentの政治的良心political conscienceを強調し、内に国民の統一national unityと外に国家の独立national independenceを求めたもの。

It emphasized the

political conscience of a constitutional government that did not align itself

with either the government or the Democratic Party, and called for national

unity internally and national independence externally.

徳富蘇峰(とくとみ・そほう)Tokutomi Sohō(徳富猪一郎(とくとみ・いいちろう)Tokutomi Iichirō)

民友社(みんゆうしゃ)Minyushaを創設した徳富蘇峰(とくとみ・そほう)Tokutomi Sohō(徳富猪一郎(とくとみ・いいちろう)Tokutomi Iichirō)らが発行した評論誌the critical magazine『国民之友(こくみんのとも)Kokumin no Tomo』を中心とする平民主義(へいみん・しゅぎ)Commonerism(日本は、一般国民(平民)の側からの西洋文明の受容による近代化を推し進めるべきだとの論)。

Commonerism centered on

the critical magazine ``Kokumin no Tomo'' published by Tokutomi Soho (Iichiro)

and others who founded Minyusha.

個人の自由と平等individual

freedom and equalityを基にして、日本の開明化Japan's enlightenmentを進めようとしたもの。

It was an attempt to

advance Japan's enlightenment based on individual freedom and equality.

加藤弘之(かとう・ひろゆき)Katō Hiroyuki

元田永孚(もとだえいふ)Motoda Eifu

これらはいずれも、1880年代後半からドイツの国家主義的思想German nationalist ideasを取り入れ、『人権新説(じんけん・しんせつ)Human Rights Shinsetsu』を書き天賦人権論(てんぷ・じんけん・ろん)the theory of natural human rightsを攻撃した加藤弘之(かとう・ひろゆき)Katō Hiroyuki(のち東大総長president of the University of Tokyo)や、儒教的国家主義Confucian nationalismを唱えた侍講(じこう)imperial tutor(君主に仕え、学問を講義すること)元田永孚(もとだえいふ)Motoda Eifuなどの官製officialの国家主義(こっかしゅぎ)Statism(自身の国家(≒政府)を第一義的に考え、その権威や意志を尊重する政治思想)とは違って、単なる反動思想reactionary ideologyではなかった。

These include Hiroyuki

Kato (later president of the University of Tokyo), who adopted German

nationalist ideas from the late 1880s and wrote the ``Human Rights Shinsetsu,''

attacking the theory of natural human rights, and the samurai who advocated

Confucian nationalism. Unlike the official nationalism of Komotoda Eifu and

others, it was not simply a reactionary ideology.

高山樗牛(たかやま・ちょぎゅう)Takayama

Chogyū

土井晩翠(どい・ばんすい)Doi Bansui

雑誌magazine『太陽(たいよう)Taiyo』の主幹the chief executive高山樗牛(たかやま・ちょぎゅう)Takayama Chogyūは、日本主義(にほんしゅぎ)Japaneseism(明治政府の極端な欧化主義に対する反動として起こり、日本古来の伝統的な精神を重視しこれを国家・社会の基調としようとした国家主義思想)を唱えて日本の大陸進出expand

into the continentを認めるなどこの転回を代表し、文壇the literary worldでも折から浪漫主義(ろうまんしゅぎ)文学romantic

literatureの時代に入り、土井晩翠(どい・ばんすい)Doi Bansuiの『万里長城の歌(ばんりのちょうじょう・の・うた)Song of the Great Wall』などが、日清戦争(にっしん・せんそう)First Sino–Japanese War後の膨張主義の風潮the expansionist trendに乗じて大きな社会的影響major social impactを与えるようになった。

Chogyu Takayama, the

chief executive of the magazine Taiyo, was representative of this turn,

advocating Japaneseism and allowing Japan to expand into the continent, and the

literary world entered the era of romantic literature at the same time, leading

to Doi Bansui. Sui)'s ``Song of the Great Wall'' and other works took advantage

of the expansionist trend that followed the Sino-Japanese War and began to have

a major social impact.

片山潜(かたやま・せん)Katayama Sen

日清戦争(にっしん・せんそう)First Sino–Japanese War・日露戦争(にちろ・せんそう)the Russo-Japanese Warをへて資本主義capitalismが急速な発達をとげ、社会矛盾social contradictionsが深刻化するとともに、社会主義思想socialist ideasも芽生えてきた。

After the Sino-Japanese

and Russo-Japanese wars, capitalism developed rapidly, social contradictions

became more serious, and socialist ideas began to emerge.

安部磯雄(あべ・いそお)Abe Isoo

1898年(明治31年)、片山潜(かたやま・せん)Katayama Sen・安部磯雄(あべ・いそお)Abe Isooらによって社会主義研究会the Socialist Study Groupが作られ、1900年(明治33年)には社会主義協会the

Socialist Associationに発展した。

In 1898 (Meiji 31), the

Socialist Study Group was created by Katayama Sen, Abe Isoo, and others, and in

1900 (Meiji 33) it developed into the Socialist Association.

幸徳秋水(こうとく・しゅうすい)Kōtoku Shūsui

ここに結集した社会主義者The socialistsは、片山潜(かたやま・せん)Katayama Sen・安部磯雄(あべ・いそお)Abe Isooらのようにキリスト教的人道主義Christian humanismから出た者と、幸徳秋水(こうとく・しゅうすい)Kōtoku Shūsuiのように自由民権論the

liberal people's rights theoryの急進派the radical wingから出発した者とがあった。

The socialists who

gathered here included those who came from Christian humanism, such as Sen

Katayama and Isoo Abe, and those who started from the radical wing of the

liberal people's rights theory, such as Shusui Kotoku.

しかしこれらのうちから、幸徳秋水(こうとく・しゅうすい)Kōtoku Shūsuiや片山潜(かたやま・せん)Katayama Senはしだいにマルクス主義的社会主義Marxist socialismの立場にすすみ、幸徳秋水(こうとく・しゅうすい)Kōtoku Shūsuiは1901年(明治34年)『廿世紀之怪物帝国主義(にじっせいきのかいぶつていこくしゅぎ)The Monstrous Imperialism of the Last Century』を著して、帝国主義imperialismの本質the

essenceと日本帝国主義Japanese imperialismの特質を痛烈に批判した。

However, among these,

Shusui Kotoku and Sen Katayama gradually advanced to the position of Marxist

socialism, and in 1901 (Meiji 34), Shusui Kotoku wrote ``The Monstrous

Imperialism of the Last Century'', which explained the essence of imperialism.

He harshly criticized the characteristics of Japanese imperialism.

神社神道(じんじゃ・しんとう)Shrine Shinto

宗教Religion

早くから政府the governmentの保護protectedを受けた神社神道(じんじゃ・しんとう)Shrine Shintoは、国家主義的教育nationalist educationの強化、記紀の神典化the divinization of the Kikiが進むとともに、神道(しんとう)Shintoは宗教religionではなく、キリスト教Christianity・仏教Buddhismなどとは一線を画すとされ、宗教界the religious worldで特殊な地位special groupを与えられた。

Shrine Shinto was

protected by the government from an early stage, and with the strengthening of

nationalist education and the development of sacred records, Shinto was

considered not to be a religion but to be distinct from Christianity, Buddhism,

etc., and became a special group in the religious world. given a position.

黒住教(くろずみ・きょう)Kurozumikyō

金光教(こんこう・きょう)Konkokyo

天理教(てんり・きょう)Tenrikyo

出口なお(でぐち・なお)Nao Deguchi

しかし、資本主義の矛盾contradictions of capitalismの激化に苦しむ民衆の間では、平易な教義simple doctrinesと現世利益the benefits of this worldを説く、幕末the end of the Edo period以来の教派神道(きょうは・しんとう)Sect Shintoである黒住教(くろずみ・きょう)Kurozumikyō・金光教(こんこう・きょう)Konkokyo・天理教(てんり・きょう)Tenrikyoや新興の大本教(おおもと・きょう)Oomotokyo(1892年(明治25年)立宗、開祖Founder出口なお(でぐち・なお)Nao Deguchi)などが、しだいにひろがっていった。

However, among the people

who are suffering from the intensifying contradictions of capitalism, there are

many Shinto sects that have existed since the end of the Edo period, such as

Kurozumi, Konko, and Tenrikyo, which preach simple doctrines and the benefits

of this world, and the emerging Oomoto sect. (Oomoto) (1892 (Meiji 25) Rissou,

Founder Deguchi Nao) etc. gradually spread.

それに対して、政府the governmentは認可approvalを与えて布教proselytizeを許したが、同時に厳しい監視と弾圧strict surveillance and oppressionを加え続けた。

In response, the

government granted approval and allowed them to proselytize, but at the same

time continued to impose strict surveillance and oppression.

南条文雄(なんじょう・ぶんゆう)Nanjo Bunyu

仏教(ぶっきょう)Buddhismは、神仏分離(しんぶつ・ぶんり)Shinbutsu

bunri(the separation of

Shintoism and Buddhism)や廃仏毀釈(はいぶつ・きしゃく)Haibutsu kishaku(abolish

Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni)で打撃を受けたが、国民思想界の主流the mainstream of national thoughtは依然として仏教(ぶっきょう)Buddhismにあり、1890年代頃から国家主義nationalismの一翼を担って次第に回復し、教団の近代的な改組the modernization of the sectに努めた浄土真宗(じょうど・しんしゅう)Jōdo Shinshūと日蓮宗(にちれん・しゅう)Nichiren-shūが、早く活動を始めた。

Although Buddhism

suffered a blow from the separation of Shinto and Buddhism and the

anti-Buddhist movement, Buddhism remained the mainstream of national thought,

and from around the 1890s it played a part in nationalism, gradually

recovering, and the modernization of the sect. The Jodo Shinshu sect and the

Nichiren sect, which strove to reorganize, quickly began their activities.

井上円了(いのうえ・えんりょう)Inoue Enryō

同時に、インド哲学Indian philosophyや仏典Buddhist scripturesについての教学研究academic researchの気運が高まり、原担山(はら・たんざん)Hara Tanzan・南条文雄(なんじょう・ぶんゆう)Nanjo Bunyu・井上円了(いのうえ・えんりょう)Inoue Enryōらの仏教学者Buddhist scholarsが輩出した。

At the same time, there

was a growing momentum for academic research on Indian philosophy and Buddhist

scriptures, producing Buddhist scholars such as Tanzan Hara, Bunyu Nanjo, and

Enryo Inoue.

島地黙雷(しまじ・もくらい)Shimaji

Mokurai

ほかに島地黙雷(しまじ・もくらい)Shimaji Mokurai・清沢満之(きよさわ・まんし)Kiyozawa Manshiのように、仏教界the Buddhist worldの革新運動revolutionary movementsに乗り出す者も出てきた。

Others, such as Mokurai

Shimachi and Manshi Kiyosawa, have embarked on revolutionary movements in the

Buddhist world.

ジェームス・カーティス・ヘボンJames Curtis Hepburn

新島襄(にいじま・じょう)Niijima Jō

キリスト教Christianityは、1873年(明治6年)に一応黙認されたが、こののち外国人宣教師foreign missionariesたち(ヘボンJames Curtis Hepburn・フルベッキHrubeckiなど)や、日本人教徒Japanese Christians(植村正久(うえむら・まさひさ)Uemura Masahisa・新島襄(にいじま・じょう)Niijima Jōなど)によって熱心に伝道evangelizedされていった。

It was tentatively

approved in 1873 (Meiji 6), but later on by foreign missionaries (such as

Hepburn Hrubecki) and Japanese Christians (such as Masahisa Uemura and Jo

Niijima). He was enthusiastically evangelized.

植村正久(うえむら・まさひさ)Uemura

Masahisa

日本人による最初の教会The

first church built by Japaneseは、植村正久(うえむら・まさひさ)Uemura Masahisaによって横浜Yokohamaに建てられていたが(1872年(明治5年))、熊本洋学校(くまもと・ようがっこう)Kumamoto Western School(1871年(明治4年)創立)・札幌農学校(さっぽろ・のうがっこう)Sapporo Agricultural College(1876年(明治9年)開校)など外国人教師foreign

teachersに指導された学校に学ぶ学生The number of students studying at schoolsは次第に増え、国家主義的風潮the nationalist trendが強まるといろいろな迫害persecutionsが強まったが、その迫害persecutionsに抗して優れた人材talented peopleが少なからず生まれ始めた。

The first church built by

Japanese was built by Masahisa Uemura in Yokohama (1872), Kumamoto Western

School (founded in 1871) and Sapporo Agricultural College (founded in 1871).

The number of students studying at schools taught by foreign teachers (opened

in 1876 (Meiji 9)) gradually increased, and as the nationalist trend

strengthened, various persecutions intensified. It started to be born quite a

bit.

In response to this

persecution, many talented people began to emerge.

ウィリアム・スミス・クラークWilliam

Smith Clark

「少年よ、大志を抱け この老人の如く」

「Boys, be ambitious like

this old man」

内村鑑三(うちむら・かんぞう)Uchimura

Kanzō

新渡戸稲造(にとべ・いなぞう)Nitobe Inazō

ジェーンズLeroy Lansing

Janesが教えた熊本洋学校(くまもと・ようがっこう)Kumamoto Western Schoolから出た海老名弾正(えびな・だんじょう)Ebina Danjo・小崎弘道(こざき・ひろみち)Kozaki Hiromichiや、クラークWilliam Smith Clarkが「青年よ、大志を抱けBoys, be ambitious like this old man」とキリスト教人道主義Christian humanismで励ました札幌農学校(さっぽろ・のうがっこう)Sapporo Agricultural Collegeから出た内村鑑三(うちむら・かんぞう)Uchimura Kanzō・新渡戸稲造(にとべ・いなぞう)Nitobe Inazōらは特に有名である。

Danjo Ebina and Hiromichi

Kozaki graduated from the Kumamoto Western School, where Janes taught, and the

Sapporo Agricultural College, where Clark encouraged him with his Christian

humanism, ``Young men, be ambitious.'' Kanzo Uchimura and Inazo Nitobe are particularly

famous.

元田永孚(もとだ・えいふ)Motoda Eifu

教育Education

民間におけるナショナリズムNationalism(自分たち国民、民族を重視するという考え)の台頭より早く、明治政府the Meiji governmentは、自由民権運動the Freedom and People's Rights Movementの高まりや民権思想the

People's Rights ideologyの発達に対抗して、儒教道徳Confucian moralityによって国民の国家観the people's view of the nationを育成しようとした。

Earlier than the rise of

nationalism in the private sector, the Meiji government sought to foster the

people's view of the nation through Confucian morality in response to the rise

of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement and the development of the People's

Rights ideology.

1882年(明治15年)、侍講(じこう)imperial tutor(君主に仕え、学問を講義すること)元田永孚(もとだ・えいふ)Motoda Eifuが勅命imperial orderで書いた『幼学綱要(ようがく・こうよう)Yogaku Koyo』を少年の教訓a lesson for boysとして全国に配布したのは、その早い表れであった。

An early manifestation of

this was in 1882 (Meiji 15), when Samurai Ko Motoda Eifu wrote the ``Yogaku

Kogyo'' by imperial order and distributed it throughout the country as a lesson

for boys.

津田梅子(つだ・うめこ)Tsuda Umeko

成瀬仁蔵(なるせ・じんぞう)Naruse Jinzō

1899年(明治32年)には高等女学校令(こうとう・じょがっこうれい)the Ordinance for Girls' High Schoolsが出され、1900年(明治33年)には津田梅子(つだ・うめこ)Tsuda Umekoが女子英学塾(じょし・えいがくじゅく)Girls' English School(のち津田塾大学(つだじゅく・だいがく)Tsuda University)、翌1901年(明治34年)には成瀬仁蔵(なるせ・じんぞう)Naruse Jinzōが日本女子大学校(にほん・じょし・だいがっこう)Japan Women's Universityを設立したが、女子高等教育higher education for womenの発達developmentはなお次の大正時代the Taisho eraを待たなければならなかった。

In 1899 (Meiji 32), the

Ordinance for Girls' High Schools was issued, and in 1900 (Meiji 33), Tsuda

Umeko established Girls' English School (Nichi Tsuda College), and the

following year, 1901 (Meiji 34), Naruse Jinzo Naruse founded the Japan Women's

College, but the development of higher education for women had to wait until

the Taisho era.

教育勅語(きょういく・ちょくご)Imperial

Rescript on Education

元田永孚(もとだ・えいふ)Motoda Eifu

学校令(がっこうれい)the School

Ordinanceの公布以来、国家主義的教育統制nationalistic educational controlを目指した政府the

governmentは、帝国憲法(ていこく・けんぽう)the Imperial Constitution発布の翌1890年(明治23年)に、国民教育national

educationおよび国民道徳national moralityの最高規範the highest standardとして教育勅語(きょういく・ちょくご)Imperial Rescript on Educationを発布した。

After the promulgation of

the School Ordinance, the government aimed at nationalistic educational

control, and in 1890 (Meiji 23), the year after the promulgation of the

Imperial Constitution, the government issued the Imperial Rescript on Education

as the highest standard for national education and national morality. did.

井上毅(いのうえ・こわし)Inoue Kowashi

教育勅語(きょういく・ちょくご)Imperial

Rescript on Educationは、元田永孚(もとだ・えいふ)Motoda Eifu・井上毅(いのうえ・こわし)Inoue Kowashiらが草案を作成したもので、最初に水戸学的な国家観the Mito-style view of the nationを述べ、そのあとに儒教的徳目Confucian

virtuesを列挙してあった。

The Imperial Rescript on

Education was drafted by Motoda Eifu, Inoue Kowashi, and others, and first

stated the Mito-style view of the nation, followed by a list of Confucian

virtues.

井上哲次郎(いのうえ・てつじろう)Inoue

Tetsujirō

そして、翌1891年(明治24年)にはその意味を注釈annotated its meaningした井上哲次郎(いのうえ・てつじろう)Inoue Tetsujirōの『勅語衍義(ちょくご・えんぎ)Chokugoengi』が出され、時代とともに国家主義的nationalistic・軍国主義的解釈militaristic interpretationsが加えられ、学校教育school educationのあらゆる機会をとらえて、学生・生徒・児童に教え込まれた。

In the following year,

1891 (Meiji 24), Tetsujiro Inoue's ``Chokugoengi'' was published, which

annotated its meaning. It was instilled in students, students, and children at

every educational opportunity.

Over time, nationalistic

and militaristic interpretations were added, and they were instilled in

students, students, and children at every opportunity of school education.

Plato's Academy mosaic,

made between 100 BCE to 79 AD, shows many Greek philosophers and scholars

科学Science

北里柴三郎(きたさと・しばさぶろう)Kitasato

Shibasaburō(1852~1931)

A bacteriologist from

Kumamoto Prefecture.

ドイツ留学studying in

Germany中、コッホRobert Kochに師事し、破傷風菌(はしょうふうきん)Clostridium tetaniの純粋分離(じゅんすい・ぶんり)the isolation of pureや、免疫血清(めんえき・けっせい)immune serumによる血清療法(けっせい・りょうほう)serum therapyの確立など、歴史的な業績をのこした。

While studying in

Germany, he studied under Koch and achieved historic achievements such as the

isolation of pure Clostridium tetani and the establishment of serum therapy

using immune serum.

そのほか、インフルエンザ桿菌(かんきん)Klebsiella influenzaeやペスト菌Yersinia pestisも発見している。

In addition, Klebsiella

influenzae and Yersinia pestis were also discovered.

また、北里研究所(きたさと・けんきゅうしょ)The Kitasato Instituteの設立や新しい医学教育の指導などにも力をつくし、門下disciplesに志賀潔(しが・きよし)Kiyoshi Shigaらがいる。

He also devoted himself

to establishing the Kitasato Research Institute and providing guidance on new medical

education, and his disciples include Kiyoshi Shiga.

志賀潔(しが・きよし)Kiyoshi Shiga(1870~1957)

1896年(明治29年)帝国大学医科大学Imperial University School of Medicine(東京大学医学部University of Tokyo School of Medicine)卒業とともに北里柴三郎(きたさと・しばさぶろう)Kitasato Shibasaburōが所長をつとめる伝染病研究所the Institute of Infectious Diseasesにはいり、細菌学(さいきんがく)bacteriologyと免疫学(めんえきがく)immunologyの研究に従事。

In 1896 (Meiji 29), upon

graduating from Imperial University School of Medicine (University of Tokyo

School of Medicine), he entered the Institute of Infectious Diseases, headed by

Kitasato Shibasaburo, and engaged in research in bacteriology and immunology.

赤痢菌(せきりきん)Shigellaの発見。

Discovery of Shigella.

秦佐八郎(はた・さはちろう)Sahachiro

Hata(1873~1938)

北里柴三郎(きたさと・しばさぶろう)Kitasato

Shibasaburōの門下で、ドイツGermanyに留学し薬学(やくがく)Pharmacyを研究。

He went to Germany to

study pharmaceutical science under Shibasaburo Kitasato.

ドイツGermanの細菌学者(さいきんがくしゃ)bacteriologistエールリヒPaul Ehrlichと共同で梅毒(ばいどく)Syphilisの化学療法剤(かがくりょうほうざい)chemotherapeutic agentsサルバルサンSalvarsanを発見。

In collaboration with

German bacteriologist Ehrlich, he discovered salvarsan, a chemotherapeutic

agent for syphilis.

野口英世(のぐち・ひでよ)Hideyo

Noguchi(1876~1928)

A bacteriologist from Fukushima Prefecture.

梅毒(ばいどく)スピロヘータsyphilis spirocheteの研究で世界的に知られる。

Known worldwide for his research on the syphilis spirochete.

ほかに、黄熱(おうねつ)Yellow fever、オロヤ熱Oroya fever、トラコーマTrachomaなどの研究にたずさわる。

He is also involved in research on yellow fever, Oroya fever, and

trachoma.

また、幼少時に左手が不自由になるほどの大やけどをおいながら、苦難を克服していくさまは、多くの伝記によって知られる。

In addition, many biographies have written about how he overcame hardships

despite sustaining severe burns that crippled his left hand as a child.

アフリカAfricaのアクラAccra(現ガーナGhanaの首都capital)で、黄熱(おうねつ)Yellow feverの研究中に感染して死去。

He died of infection

while researching yellow fever in Accra, Africa (currently the capital of

Ghana).

高峰譲吉(たかみね・じょうきち)Takamine

Jōkichi(1854~1922)

消化促進作用promotes

digestionをもつ酵素複合体enzyme complexタカジアスターゼTakadiastaseの抽出に成功。

Succeeded in extracting

Takadiastase, an enzyme complex that promotes digestion.

アドレナリンAdrenalineの発明。

Invention of Adrenaline.

鈴木梅太郎(すずき・うめたろう)Umetaro

Suzuki(1874~1943)

1910年(明治43年)、国民病a national diseaseといわれた脚気(かっけ)beriberiに有効なビタミンB1(チアミンThiamine)を米ぬかrice branから抽出することに成功して、のちオリザニンOryzaninと名づけた。

In 1910 (Meiji 43), he

succeeded in extracting vitamin B1 from rice bran, which was effective against

beriberi, which was said to be a national disease, and later named it Oryzanin.

長岡半太郎(ながおか・はんたろう)Hantaro

Nagaoka(1865~1950)

わが国の理論物理学(りろん・ぶつりがく)Theoretical physicsの先駆者。

A pioneer of theoretical

physics in Japan.

初代の大阪大学Osaka University総長presidentとなった。

He became the first

president of Osaka University.

磁気(じき)ひずみMagnetostrictionの研究。

Magnetostriction

research.

原子構造Atomic Structureの理論theoryを発表。

Published theory of Atomic

Structure.

池田菊苗(いけだ・きくなえ)Kikunae Ikeda(1864~1936)

明治中期から昭和初期の化学者chemist。

A chemist from the

mid-Meiji period to the early Showa period.

化学調味料the chemical

seasoning「味の素(あじのもと)Ajinomoto」の発明者。

Inventor of the chemical

seasoning ``Ajinomoto.''

牧野富太郎(まきの・とみたろう)Tomitaro Makino(1862~1957)

独学で植物の研究plant researchに従事。

Self-taught and engaged

in plant research.

1889年(明治22年)、日本植物Japanese plantsに日本人としてはじめて学名を与えるなど植物分類学(しょくぶつ・ぶんるいがく)plant taxonomyに功績大。

In 1889 (Meiji 22), he was

the first Japanese to give scientific names to Japanese plants, making great

achievements in plant taxonomy.

『牧野植物学全集Makino Botany Complete Works』・『日本植物志図篇Japanese Botany Illustrated Edition』。

``Makino Botany Complete

Works'' and ``Japanese Botany Illustrated Edition''.

西周(にし・あまね)Nishi Amane

津田真道(つだ・まみち)Tsuda Mamichi

Philosophieという語を「哲学(てつがく)philosophy」と訳出したのは西周(にし・あまね)Nishi Amaneであったが、西周(にし・あまね)Nishi Amaneや津田真道(つだ・まみち)Tsuda Mamichiによって実証主義哲学(じっしょう・しゅぎ・てつがく)positivist philosophyが紹介された。

It was Nishi Amane who

translated the word Philosophie as ``philosophy,'' but positivist philosophy

was introduced by Nishi Amane and Tsuda Michi.

井上哲次郎(いのうえ・てつじろう)Inoue

Tetsujirō

これは、封建的儒教思想feudal Confucianismに代わる思想的立場ideological positionを求めた当時の人々にひろく受け入れられ影響を与えたが、憲法制定the enactment of the Constitution、ナショナリズムNationalism(自分たち国民、民族を重視するという考え)の台頭the riseとともに、カントImmanuel Kant・ヘーゲルGeorg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegelなどのドイツ観念論哲学(かんねんろん・てつがく)German idealist philosophyが盛んとなり、井上哲次郎(いのうえ・てつじろう)Inoue Tetsujirō・大西祝(おおにし・はじめ)Ōnishi Hajimeらを先駆者Pioneersとして、桑木厳翼(くわき・げんよく)Kuwaki Gen’yokuなどが出た。

This was widely accepted

and influenced by the people of the time who sought an alternative ideological

position to feudal Confucianism, but with the enactment of the Constitution and

the rise of nationalism, German idealist philosophy such as Kant Hegel

flourished, and Tetsujiro Inoue Pioneers include Tetsujiro Inoue and Hajime

Onishi, followed by Genyoku Kuwaki and others.

ボワソナードGustave Boissonade

法学(ほうがく)は、明治政府the Meiji governmentの諸制度various systemsの近代的改革the modern reformsと直接に触れ合いながら発達した。

Jurisprudence developed

through direct contact with the modern reforms of various systems of the Meiji

government.

梅謙次郎(うめ・けんじろう)Ume Kenjirō

穂積陳重(ほづみ・のぶしげ)Hozumi

Nobushige

初めはボアソナードGustave Boissonadeなどの指導もありフランス法French lawが主で、梅謙次郎(うめ・けんじろう)Ume Kenjirōなどが出たが、憲法制定の準備過程でドイツ法学German

jurisprudenceが優勢となり、穂積陳重(ほづみ・のぶしげ)Hozumi Nobushigeらが出た。

At first, French law was

predominant, with the guidance of Boissonade and others, including Kenjiro Ume,

but in the process of preparing the constitution, German jurisprudence became

dominant, and Hozumi Nobushige and others appeared.

金井延(かない・のぶる)Kanai Noburu

経済学(けいざいがく)Economics

初めはイギリスBritishの自由主義経済liberal economicsが招来されたが、やがて金井延(かない・のぶる)Kanai Noburuらによってドイツ歴史学派理論German historical school theoryや社会政策学(しゃかい・せいさく・がく)social policyが紹介され、1896年(明治29年)には社会政策学会(しゃかい・せいさく・がっかい)が設立された(命名は翌1897年(明治30年))。

At first, British liberal

economics was introduced, but later Noburu Kanai and others introduced German

historical school theory and social policy, and in 1896 (Meiji 29), the Social

Policy Society was established. (It was named the following year in 1897 (Meiji

30)).

福澤諭吉(ふくざわ・ゆきち)Fukuzawa Yukichi

田口卯吉(たぐち・うきち)Taguchi

Ukichi

歴史学(れきしがく)History

初期には、フランスFrenchやイギリスBritishの文明史(ぶんめいし)civilization historyや進化論(しんかろん)theory of evolutionの影響(ギゾーFrançois Guizotの『ヨーロッパ文明史History of European Civilization』・バックルHenry

Thomas Buckleの『イギリス文明史History of British Civilization』など)による文明史(ぶんめいし)civilization historyが流行し、福澤諭吉(ふくざわ・ゆきち)Fukuzawa Yukichiの『文明論之概略(ぶんめいろん・の・がいりゃく)Outline of Civilization Theory』、田口卯吉(たぐち・うきち)Taguchi Ukichiの『日本開化小史(にほん・かいか・しょうし)A Short History of Japanese Enlightenment』などが著された。

In the early years,

civilization history based on the influence of French and British civilization

history and evolutionary theory (Guizot's "History of European

Civilization", Buckle's "History of British Civilization", etc.)

was popular, and Yukichi Fukuzawa's "Outline of Civilization Theory" and

Taguchi's "History of Civilization" were popular. Books such as ``A

Short History of Japanese Enlightenment'' by Ukichi Taguchi were written.

三宅米吉(みやけ・よねきち)Miyake

Yonekichi

この傾向はさらに進み、三宅米吉(みやけ・よねきち)Miyake YonekichiはコントAuguste Comteの実証主義(じっしょう・しゅぎ)Positivism(実験や統計によって証明することができない現象についての研究は、学問の範疇から外すべきであるという主張)によって『日本史学提要(にほん・しがく・ていよう)』を刊行(1884年(明治17年))したが、一巻だけで中絶を余儀なくされた。

This trend progressed further,

and Miyake Yonekichi published ``Summary of Japanese History'' (1884) based on

Comte's positivism, but he was forced to abandon the book after only one

volume.

レオポルト・フォン・ランケLeopold

von Ranke

それに代わって、1887年(明治20年)に招かれて来日したリースLudwig Riessは、ドイツGermanyのランケ史学Ranke historiographyによる実証主義(じっしょう・しゅぎ)Positivismを唱え、史論的風潮the historiographical trendを批判した。

Instead, Ries, who came

to Japan by invitation in 1887 (Meiji 20), advocated positivism based on

Germany's Ranke historiography and criticized the historiographical trend.

那珂通世(なか・みちよ)Naka Michiyo

重野安繹(しげの・やすつぐ)Shigeno

Yasutsugu・久米邦武(くめ・くにたけ)Kume Kunitake・那珂通世(なか・みちよ)Naka Michiyo・白鳥庫吉(しらとり・くらきち)Shiratori Kurakichi・坪井九馬三(つぼい・くめぞう)Tsuboi Kumezōなど実証主義(じっしょう・しゅぎ)の先駆的学者Pioneering

positivist scholarsが生まれた。

Pioneering positivist scholars

such as Yasutsugu Shigeno, Kunitake Kume, Michiyo Naka, Kurakichi Shiratori,

and Kumezou Tsuboi were born.

久米邦武(くめ・くにたけ)Kume Kunitake

しかし、このような歴史学研究の転換shift in historical researchに加えて、国家主義者nationalistsから近代的歴史分析や史論modern historical analysis and theoryへの攻撃attacksが強まり、久米邦武筆禍事件(くめ・くにたけ・ひっかじけん)The Kume affairや南北朝正閏論争(なんぼくちょう・せいじゅん・ろんそう)the controversy over the Seijun of the Northern and Southern Courtsが生じたため、わが国の近代歴史学Modern

historiographyは権力分析を回避avoid analysis of powerする傾向が強くつきまとうことになった。

However, in addition to

this shift in historical research, attacks on modern historical analysis and

theory from nationalists intensified, as well as the Kume Kunitake Incident and

the controversy over the Seijun of the Northern and Southern Courts. Modern

historiography has had a strong tendency to avoid analysis of power.

福田徳三(ふくだ・とくぞう)Tokuzō Fukuda

1895年(明治28年)には、帝国大学Imperial Universityに史料編纂掛(しりょう・へんさん・がかり)Historiographical Compilation Department(のち史料編纂所(しりょう・へんさん・じょ)Historiographical Institute)が置かれ、『大日本史料(だいにほん・しりょう)Dai Nihon Shiryō』・『大日本古文書(だいにほん・こもんじょ)Dainihon Komonsho』の編纂事業the compilationが始まった。

In 1895 (Meiji 28), the

Historiographical Compilation Department (later the Historiographical

Institute) was established at Imperial University, and the compilation of

``Dainihon Shiryo'' and ``Dainihon Komonsho'' began.

内田銀蔵(うちだ・ぎんぞう)Uchida Ginzō

このような影響もあって、官学界government and academiaにも福田徳三(ふくだ・とくぞう)Tokuzō Fukuda・内田銀蔵(うちだ・ぎんぞう)Uchida Ginzōのように世界史world history的な経済史的発展法則the laws of economic and historical developmentに則して日本の歴史Japanese

historyを考察considerする傾向が生じた。

Partly as a result of

this influence, a tendency arose in government and academia to consider Japanese

history in accordance with the laws of economic and historical development

based on world history, as was the case with Tokuzo Fukuda and Ginzo Uchida.

芳賀矢一(はが・やいち)Haga Yaichi

芳賀矢一(はが・やいち)Haga Yaichiが文献学(ぶんけんがく)Philologyを確立し、藤岡作太郎(ふじおか・さくたろう)Fujioka Sakutarōは文明史的視野civilizational historical perspectiveで国文学史the

history of Japanese literatureの研究researchを進めた。

Yaichi Haga established

philology, and Sakutaro Fujioka advanced research on the history of Japanese

literature from a civilizational historical perspective.

仮名垣魯文(かながき・ろぶん)Kanagaki

Robun

文学Literature

明治時代the Meiji

periodになっても、文芸の世界the world of literatureにはまだ近代文学の自立the independence of modern literatureは認められず、封建時代の傾向the trends of the feudal eraが尾を引いていた。

Even in the Meiji period,

the independence of modern literature was still not recognized in the world of

literature, and the trends of the feudal era continued.

『安愚楽鍋(あぐら・なべ)Aguranabe』

仮名垣魯文(かながき・ろぶん)Kanagaki

Robunの『西洋道中膝栗毛(せいようどうちゅう・ひざくりげ)』・『安愚楽鍋(あぐら・なべ)Aguranabe』(1871年(明治4年))に代表される戯作文学(げさく・ぶんがく)Gesaku literature、

Gesaku literature

represented by Robun Kanagaki's ``Western Way Hizakurige'' and ``Aguranabe''

(1871 (Meiji 4));

東海散士(とうかい・さんし)Tokai Sanshi

1880年代前半頃まで、自由民権運動the Freedom and People's Rights Movementで流行した東海散士(とうかい・さんし)Tokai Sanshiの『佳人之奇遇(かじん・の・きぐう)Kajin no Kiguu』(1885年(明治18年))(西欧列強に侵略された弱小民族が自由と独立をもとめる姿をえがいて青年たちの強い支持をうけた。)、

Until the early 1880s,

Tokai Sanshi's "Kajin no Kiguu" (1885), which was popular in the Freedom

and People's Rights Movement, was popular in the Freedom and People's Rights

Movement. He drew strong support from young people, depicting him demanding

independence.)

矢野竜渓(やの・りゅうけい)Yano Ryūkei

矢野竜渓(やの・りゅうけい)Yano Ryūkeiの『経国美談(けいこく・びだん)Keikoku Bidan』(1883年(明治16年))(民主政治をうちたてた古代ギリシャのテーベの史実を素材に、民主的国家の建設や祖国愛をうったえて好評をえた。)、

Ryukei Yano's ``Keikoku

Bidan'' (1883 (Meiji 16)) (Based on the historical facts of Thebes in ancient

Greece, which established democratic government, talks about the construction

of a democratic state and It was well-received as it expressed love for the

motherland.)

末広鉄腸(すえひろ・てっちょう)Tetchō

Suehiro

末広鉄腸(すえひろ・てっちょう)Tetchō

Suehiroの『雪中梅(せっちゅうばい)Setchūbai』(民権運動の志士、国野基(くにのもとい)と彼に資金援助をしてきたお春が最後にむすばれるという政治色よりも風俗色を強めた作品として人気をえた。)、

Suehiro Teccho's

``Setschuubai'' (a political story in which Motoi Kunino, a patriot of the

civil rights movement, and Oharu, who had provided financial support to him,

die in the end) It gained popularity as a work with a stronger sex appeal.)

宮崎夢柳(みやざき・むりゅう)Muryu Miyazak

宮崎夢柳(みやざき・むりゅう)Muryu Miyazakの『鬼啾々(きしゅうしゅう)Kishushuu』(革命をめざすロシアのテロリストをえがいて、秩父事件など自由民権運動の激化事件が頻発する中で大きな反響をよんだ。)などに代表される政治小説(せいじ・しょうせつ)Political novels、

Muryu Miyazaki's

``Kishushuu'' (depicting Russian terrorists aiming for a revolution, it received

a great response amidst the frequent incidents of intensification of the civil

rights movement such as the Chichibu Incident), etc. Political novels

represented by

あるいは雑多に出され始めた翻訳小説(ほんやく・しょうせつ)the translated novelsなどがそれである。

Another example is the

translated novels that have begun to be widely published.

坪内逍遥(つぼうち・しょうよう)Tsubouchi

Shōyō

このような文学界the literary worldの傾向に対し、1885年(明治18年)に坪内逍遥(つぼうち・しょうよう)Tsubouchi Shōyōは『小説神髄(しょうせつ・しんずい)』を著して、これまでの戯作(げさく)Gesakuや勧善懲悪的文学literature that promoted good and evilを否定して、文学の自主性literary independenceと写実主義(しゃじつ・しゅぎ)Realismを主張した。

In response to this trend

in the literary world, in 1885 (Meiji 18) Shoyo

Tsubouchi wrote ``The Essence of Novel'' (Shosetsu Shinzui), in which he wrote

about the past plays and the promotion of good, punishment, and evil. He

rejected traditional literature and insisted on literary autonomy and realism.

He rejected the

conventional plays and literature that promoted good and evil, and advocated

literary independence and realism.

『当世書生気質(とうせい・しょせい・かたぎ)Toseisho Seikatagi』

そして彼は、自らその作品化turn this idea into a workの試みとして『当世書生気質(とうせい・しょせい・かたぎ)Toseisho Seikatagi』を書いた。

As an attempt to turn

this idea into a work, he wrote ``Toseisho Seikatagi.''

二葉亭四迷(ふたばてい・しめい)Futabatei

Shimei

『浮雲(うきぐも)Ukigumo』

しかし、坪内逍遥(つぼうち・しょうよう)Tsubouchi Shōyōの主張した文学論the literary theoryを、戯作(げさく)Gesakuにおいて最初に成功させたのは、二葉亭四迷(ふたばてい・しめい)Futabatei Shimeiが言文一致体(げんぶんいっちたい)Genbun Ichitaiの文章を用いて書いた『浮雲(うきぐも)Ukigumo』(1887年(明治20年))であり、彼はこの作品で人間性の苦悩the suffering of humanityをリアルに描いた。

However, the literary

theory advocated by Shoyo Tsubouchi was first succeeded in writing by Futaba

Tei Shimei, who used the text of Genbun Ichitai to write ``Ukigumo''.

(Ukigumo)'' (1887), in which he realistically depicted the suffering of humanity.

また『あひびきAhibiki』・『めぐりあひMeguriahi』などの翻訳translationsでロシア文学Russian literatureを紹介した。

He also introduced

Russian literature through translations such as ``Ahibiki'' and ``Meguriahi.''

硯友社(けんゆうしゃ)Ken'yūsha

硯友社社友。後列左より武内桂舟、川上眉山、江見水蔭。前列左より巌谷小波、石橋思案、尾崎紅葉。1891年

硯友社(けんゆうしゃ)Ken'yūsha

しかし、当時の人々から最も喜ばれ、小説の普及popularizing novelsに功績のあったのは、江戸文芸の伝統the Edo literary traditionに写実主義(しゃじつ・しゅぎ)Realismを加えた尾崎紅葉(おざき・こうよう)Ozaki Kōyōと、彼を中心とする硯友社(けんゆうしゃ)Ken'yūshaの人々であった。

However, the people who were

most appreciated by the people of the time and who were most successful in popularizing

novels were Koyo Ozaki, who added realism to the Edo literary tradition, and

Kenyusha, which was centered around him. They were the people of

硯友社(けんゆうしゃ)Ken'yūshaは尾崎紅葉(おざき・こうよう)Ozaki Kōyōを中心に1885年(明治18年)に組織され、機関紙the journal『我楽多文庫(がらくた・ぶんこ)Garakuta Bunko』を発行した。

Kenyusha was organized in

1885 (Meiji 18), led by Momiji Ozaki, and published the journal ``Garakuta

Bunko.''

尾崎紅葉(おざき・こうよう)Ozaki Kōyō

『金色夜叉(こんじき・やしゃ)Konjiki Yasha』

山田美妙(やまだ・びみょう)Yamada Bimyō

川上眉山(かわかみ・びざん)Bizan

Kawakami

広津柳浪(ひろつ・りゅうろう)Hirotsu Ryurō

泉鏡花(いずみ・きょうか)Kyōka Izumi

『金色夜叉(こんじき・やしゃ)Konjiki Yasha』・『多情多恨(たじょう・たこん)Tajo Takon』などを著した尾崎紅葉(おざき・こうよう)Ozaki Kōyōのほか、同人には山田美妙(やまだ・びみょう)Yamada Bimyō『胡蝶(こちょう)Kochō』・『夏木立(なつ・こだち)Natsukodachi』、川上眉山(かわかみ・びざん)Bizan Kawakami『観音岩(かんのん・いわ)Kannon Rock』、広津柳浪(ひろつ・りゅうろう)Hirotsu Ryurō『残菊(ざんぎく)Zangiku』、泉鏡花(いずみ・きょうか)Kyōka Izumiらがあった。

In addition to Momiji

Ozaki, who wrote ``Konjiki Yasha'' and ``Tajo Takon,'' other doujins include

Bimyou Yamada, ``Kochō,'' and ``Natsukidate.'' ', 'Kannon Rock' by Bizan

Kawakami, 'Zangiku' by Ryūro Hirotsu, and Kyoka Izumi.

幸田露伴(こうだ・ろはん)Kōda Rohan

『五重塔(ごじゅう・の・とう)The Five-Storied Pagoda』

幸田露伴(こうだ・ろはん)Kōda Rohanは、『五重塔(ごじゅう・の・とう)The Five-Storied Pagoda』(1891年(明治24年))・『風流仏(ふうりゅう・ぶつ)Furyubutsu』(1889年(明治22年))などを書いて理想主義idealisticにたった独自の作風his own unique styleをひらき尾崎紅葉(おざき・こうよう)Ozaki Kōyōとともに紅露時代(こうろ・じだい)the Koro periodと称された。

Kouda Rohan became

idealistic by writing such works as ``Five-storied Pagoda'' (1891 (Meiji 24))

and ``Furyubutsu'' (1889 (Meiji 22)). He developed his own unique style, and

together with Momiji Ozaki, it was called the Koro period.

北村透谷(きたむら・とうこく)Kitamura

Tokoku

ロマン主義文学Romanticism Literature

資本主義capitalismの発達と日清戦争(にっしん・せんそう)First Sino–Japanese Warの勝利は、自我意識の目覚めawakening of self-awarenessや理想主義idealismを高め、また、従来の啓蒙主義・理性万能主義Enlightenment and rationalismに対して主情的傾向tendency toward self-interestが強まった。

The development of

capitalism and the victory in the Sino-Japanese War led to an awakening of self-awareness

and increased idealism, and a tendency toward self-interest became stronger in

contrast to the conventional Enlightenment and rationalism.

島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson

Shimazaki

1893年(明治26年)、雑誌the magazine『文学界(ぶんがくかい)Bungakukai(Literary World)』が北村透谷(きたむら・とうこく)Kitamura Tokoku・島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson Shimazakiらによって創刊されて以来、日露戦争(にちろ・せんそう)the Russo-Japanese War前後まで約10年間は詩poetryと文学literatureにロマン主義Romanticismの最盛期its peakを迎えた。

In 1893 (Meiji 26), the

magazine ``Bungakukai'' was launched by Tokoku Kitamura, Toson Shimazaki, and

others, and for about 10 years until around the Russo-Japanese War, he focused

on poetry and literature. Romanticism was at its peak.

森鷗外(もり・おうがい)Mori Ōgai

『舞姫(まいひめ)The Dancing Girl』

小説(しょうせつ)Novel

森鷗外(もり・おうがい)Mori Ōgaiは1889年(明治22年)に訳詩集collection

of translated poems『於母影(おもかげ)Omokage』を発表し、以後『うたかたの記(うたかたのき)』・『舞姫(まいひめ)The Dancing Girl』、翻訳『即興詩人(そっきょう・しじん)The Improvisatore』などを発表して、先駆的役割pioneering roleを果たした。

Mori Ogai published a

collection of translated poems ``Omokage'' in 1889 (Meiji 22), and has since

published works such as ``Utakata no Ki'', ``Maihime'', and ``Impromptu Poet'',

etc. He played a pioneering role in announcing this.

樋口一葉(ひぐち・いちよう)Ichiyō

Higuchi

『たけくらべTakekurabe(Comparing heights)』

高山樗牛(たかやま・ちょぎゅう)Takayama

Chogyū

『滝口入道(たきぐちにゅうどう)Takiguchi Nyudo』

国木田独歩(くにきだ・どっぽ)Doppo

Kunikida

徳冨蘆花(とくとみ・ろか)Tokutomi Roka

『不如帰(ほととぎす)Hototogisu』

泉鏡花(いずみ・きょうか)Kyōka Izumi

『高野聖(こうや・ひじり)Kōya Hijiri』

そして1890年代に入ってから発表された樋口一葉(ひぐち・いちよう)Ichiyō Higuchiの『たけくらべTakekurabe(Comparing heights)』・『にごりえNigorie』、高山樗牛(たかやま・ちょぎゅう)Takayama Chogyūの『滝口入道(たきぐち・にゅうどう)Takiguchi Nyudo』(1894年(明治27年))、国木田独歩(くにきだ・どっぽ)Doppo Kunikidaの『武蔵野(むさしの)Musashino』、『不如帰(ほととぎす)Hototogisu』などを書いた徳冨蘆花(とくとみ・ろか)Tokutomi Rokaの『自然と人生Nature and Life』、硯友社(けんゆうしゃ)文学Kenyusha

Bungakuから転じた泉鏡花(いずみ・きょうか)Kyōka Izumiの『高野聖(こうや・ひじり)Kōya Hijiri』・『湯島詣(ゆしま・もうで)Yushima Pilgrimage』など、ロマン主義作品works of Romanticismの代表作が相次いで発表されていった。

Then, in the 1890s,

Higuchi Ichiyo's ``Takekurabe'' and ``Nigorie'' were published, and Takayama

Chogyu's ``Takiguchi Nyudo'' (1894 (Meiji 27)), ``Nature and Life'' by

Tokutomiroka, who wrote ``Musashino'' by Doppo Kunikida, ``Hototogisu'', etc.,

and ``Nature and Life'' by Miroka Tokutomi, who wrote ``Musashino'' by Doppo

Kunikida, and ``Nature and Life'' by Izumi Kyoka, who turned from Kenyusha Bungaku.

Representative works of Romanticism, such as ``Koya Hijiri'' and ``Yushima

Pilgrimage'' by Kyouka, were released one after another.

やがて日露戦争(にちろ・せんそう)the Russo-Japanese War後の資本主義capitalismの諸矛盾the contradictionsの激化とともに、ロマン主義文学Romantic literatureは次第に衰退declinedした。

As the contradictions of

capitalism intensified after the Russo-Japanese War, Romantic literature

gradually declined.

外山正一(とやま・まさかず)Toyama

Masakazu

近代詩Modern poetryはすでに、1882年(明治15年)外山正一(とやま・まさかず)Toyama Masakazuらの『新体詩抄(しんたいし・しょう)』の出現に始まっていた。

Modern poetry had already

begun in 1882 (Meiji 15) with the appearance of ``Shintai Shisho'' by Sakazu

Toyama and others.

北村透谷(きたむら・とうこく)Kitamura

Tokoku

島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson

Shimazaki

『若菜集(わかな・しゅう)Wakanashu』

ロマン主義文学運動the

Romantic literary movementの理論的指導者the theoretical leaderであった北村透谷(きたむら・とうこく)Kitamura Tokokuは、『楚囚之詩(そしゅうの・し)Poetry of the Prisoners of Chu』(1889年(明治22年))・『蓬莱曲(ほうらい・きょく)Houraikyoku』などによって創作詩creative poetryの活動を試み、島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson Shimazakiは『若菜集(わかな・しゅう)Wakanashu』(1897年(明治30年))を刊行して、清澄な情熱pure passionと自我の覚醒the awakening of the egoをうたいあげた。

Kitamura Tokoku, the

theoretical leader of the Romantic literary movement, wrote ``Poetry of the

Prisoners of Chu'' (1889) and ``Hourai.'' Toson Shimazaki tried his hand at

creative poetry with works such as ``Wakanashu'' (1897), which sang of pure

passion and the awakening of the ego. gave.

土井晩翠(どい・ばんすい)Doi Bansui

土井晩翠(どい・ばんすい)は詩集collection of poems『天地有情(てんち・うじょう)Tenchi ujo』(1899年(明治32年))を出し、歴史に題材material from historyを求めて民族の理想the ideals of the nationをうたった。

Doi Bansui published a

collection of poems, ``Tenchi Yujo'' (1899), in which he sought material from

history and sang about the ideals of the nation.

上田敏(うえだ・びん)Bin Ueda

また上田敏(うえだ・びん)Bin Uedaはヨーロッパの詩European poetryを訳して『海潮音(かいちょうおん)Kaichō on』(1905年(明治38年))を出し、象徴詩(しょうちょう・し)symbolic poetryの理論theoryを提唱し、さらに『白羊宮(はく・よう・きゅう)The Palace of the White Sheep』の薄田泣菫(すすきだ・きゅうきん)Susukida Kyūkin、『有明集(ありあけ・しゅう)the Ariake Collection』の蒲原有明(かんばらありあけ)Ariake Kambaraらは、象徴詩(しょうちょう・し)symbolic poetry風styleを大成した。

Bin Ueda also translated

European poetry and published ``Kaichou-on'' (1905), proposing the theory of

symbolic poetry, and also published ``The Palace of the White Sheep''. Susukida

Kyukin, Kanbara Ariake of the Ariake Collection, and others perfected the style

of symbolic poetry.

落合直文(おちあい・なおぶみ)Ochiai

Naobumi

歌壇the poetry

worldにも、落合直文(おちあい・なおぶみ)Ochiai Naobumiが結成した浅香社(あさかしゃ)Asakashaの人々の活躍で近代化modernizationの傾向が芽生えた。

A trend toward

modernization began to emerge in the poetry world as well, thanks to the active

participation of the members of Asakasha, a group founded by Naofumi Ochiai.

明星(みょうじょう)Myojo(Bright Star) 1900年(明治33年)~1908年(明治41年)

与謝野鉄幹(よさの・てっかん)Tekkan Yosano

与謝野晶子(よさの・あきこ)Yosano Akiko

落合直文(おちあい・なおぶみ)Ochiai

Naobumi門下discipleの与謝野鉄幹(よさの・てっかん)Tekkan Yosanoは新詩社(しんししゃ)Shinshishaを組織し、1900年(明治33年)から雑誌the magazine『明星(みょうじょう)Myojo』を創刊して、歌集collection of poems『みだれ髪(みだれがみ)Midaregami』などを出した妻wifeの与謝野晶子(よさの・あきこ)とともに、ロマン主義短歌Romantic Short poemの中心となった。

Yosano Tekkan, a disciple

of Naofumi Ochiai, organized Shinshisha and started the magazine ``Myojo'' in

1900 (Meiji 33), and his wife Akiko Yosano published a collection of poems such

as ``Midaregami.'' Along with Akiko Yosano, she became the center of Romantic

tanka.

旅順攻囲戦(りょじゅん・こういせん)Siege of Port

Arthur

『君死にたまふことなかれDon't let yourself die』

1904年(明治37年)9月、与謝野晶子(よさの・あきこ)Akiko Yosanoが、半年前に召集され旅順攻囲戦(りょじゅん・こういせん)Siege of Port Arthurに従軍していた弟younger brotherを嘆いて、『明星(みょうじょう)Myojo(Bright Star)』に発表した反戦歌Anti-war

song。

In September 1904 (Meiji

37), Akiko Yosano lamented her younger brother, who

had been called up to serve in the Siege of Port Arthur six months earlier, and

wrote a book titled ``Myo Star''. This is an anti-war song published in

``Jou''.

ああをとうと(弟)よ、君を泣く、

ああ弟よ、あなたのために泣いています。

I cry for you, Brother,

君死にたまふことなかれ、

弟よ、死なないで下さい。

don't you dare lay down

your life,

末に生れし君なれば

末っ子に生まれたあなただから

You, the youngest child

in our family,

親のなさけはまさりしも、

親の愛情は(他の兄弟よりも)たくさん受けただろうけど

thus cherished all the

more-

親は刃(やいば)をにぎらせて

親は刃物を握らせて

Mother and Father didn't

educate you

人を殺せとをしへしや、

人を殺せと(あなたに)教えましたか?(そんなはずないでしょう。)

to wield weapons and to

murder; they didn't

人を殺して死ねよとて

人を殺して自分も死ねといって

bring you up, to the age

of twenty-four,

二十四(にじゅうし)までをそだてしや。

(あなたを)24歳まで育てたのでしょうか?(そんなはずないでしょう。)

so that you could kill,

or be killed yourself.

堺(さかひ)の街のあきびとの

堺の街の商人の

You were born into a long

line

旧家をほこるあるじにて

歴史を誇る家の主人で

of proud tradespeople in

the city of Sakai;

親の名を継ぐ君なれば、

親の名前を受け継ぐあなたなら

having inherited their

good name,

君死にたまふことなかれ、

(どうか)死なないで下さい。

don't you dare lay down

your life.

旅順の城はほろぶとも、

旅順の城が陥落するか

What does it matter if

that fortress

ほろびずとても、何事ぞ、

陥落しないかなんてどうでもいいのです。

on the Liaotung Peninsula

falls or not?

君は知らじな、あきびとの

あなたは知らないでしょうが、商人の

It's nothing to you, a

tradesman

家のおきてに無かりけり

家の掟には(人を殺して自分も死ねという項目など)ないのですよ。

with a tradition to

uphold.

君死にたまふことなかれ、

弟よ、死なないで下さい。

Don't you dare lay down

your life.

すめらみことは、戦ひに

天皇陛下は戦争に

The Emperor himself

doesn't go

おほみづからは出でまさね、

ご自分は出撃なさらずに

to fight at the front;

others

かたみに人の血を流し、

互いに人の血を流し

spill out their blood

there.

獣(けもの)の道に死ねよとは、

「獣の道」に死ねなどとは、

If His Majesty be indeed

just

死ぬるを人のほまれとは、

それが人の名誉などとは

and magnanimous, surely

he won't wish

大みこころの深ければ

(天皇陛下は)お心の深いお方だから

his subjects to die like

beasts,

もとよりいかで思(おぼ)されむ。

そもそもそんなことをお思いになるでしょうか。(そんなはずないでしょう。)

nor would be call such

barbarity "glory"

ああをとうとよ、戦ひに

ああ弟よ、戦争なんかで

Little Brother, don't you

dare

君死にたまふことなかれ、

(どうか)死なないで下さい。

lay down your life in

battle.

すぎにし秋を父ぎみに

この間の秋にお父様に

This autumn, Father

passed away.

おくれたまへる母ぎみは、

先立たれたお母様は

Mother manages, somehow,

to carry on,

なげきの中に、いたましく

悲しみの中、痛々しくも

but lives in constant

fear for the son

わが子を召され、家を守(も)り、

我が子を(戦争に)召集され、家を守り

who's been taken from

her-

安(やす)しと聞ける大御代も

安泰と聞いていた天皇陛下の治める時代なのに

People say ours is a

prosperous age,

母のしら髪はまさりぬる。

(苦労が重なったせいで)お母様の白髪は増えています。

yet Mother's hair has all

turned gray.

暖簾(のれん)のかげに伏して泣く

暖簾の陰に伏して泣いている

Inside the family shop,

behind the curtain,

あえかにわかき新妻(にひづま)を、

か弱くて若い新妻を

your willowy young wife

weeps alone.

君わするるや、思へるや、

あなたは忘れたのですか?それとも思っていますか?

Have you forgotten her?

Is she in your thoughts?

十月(とつき)も添はでわかれたる

10ヵ月も一緒に住まないで別れた

You two were together for

less than ten months.

少女ごころを思ひみよ、

若い女性の心を考えてごらんなさい。

Think how her heart is

wrung. There's only one

この世ひとりの君ならで

この世であなたは1人ではないのです。

of you in this world,

remember.

ああまた誰をたのむべき、

ああ、また誰を頼ったらよいのでしょう。

Your family has no one

else to turn to.

君死にたまふことなかれ。

(とにかく)弟よ、死なないで下さい。

Don't lay down your life.

北原白秋(きたはら・はくしゅう)Hakushū

Kitahara

石川啄木(いしかわ・たくぼく)Takuboku

Ishikawa

高村光太郎(たかむら・こうたろう)Kōtarō

Takamura

雑誌the magazine『明星(みょうじょう)Myojo』を中心とする明星派The Myojo schoolには、北原白秋(きたはら・はくしゅう)Hakushū Kitahara(『邪宗門(じゃしゅうもん)Jashumon』)・石川啄木(いしかわ・たくぼく)Takuboku Ishikawa・木下杢太郎(きのした・もくたろう)Mokutaro Kinoshita・高村光太郎(たかむら・こうたろう)Kōtarō Takamuraら、次の時代の歌壇the poetry worldを担った人々が属した。

The Myojo school,

centered around the magazine Myojo, includes Hakushu Kitahara (Jashumon),

Takuboku Ishikawa, Mokutaro Kinoshita, and Kotaro Takamura. ) and others who

were responsible for the singing world of the next era belonged to it.

正岡子規(まさおか・しき)Masaoka Shiki

伊藤左千夫(いとう・さちお)Itō Sachio

また『歌よみに与ふる書(うたよみに・あたうる・しょ)Utayomini Atauru sho』(1898年(明治31年))で、早くから和歌の革新innovation of wakaを主張してきた正岡子規(まさおか・しき)Masaoka Shikiは、写実主義(しゃじつ・しゅぎ)Realismを強調して万葉調の素朴な歌風a simple Manyo style of poetryをなし、やがてこの門流this schoolから出た伊藤左千夫(いとう・さちお)Itō Sachio・長塚節(ながつか・たかし)Takashi Nagatsukaらは、1908年(明治41年)に短歌雑誌the tanka magazine『アララギAraragi』を刊行し、歌壇の主流the mainstream of the poetry worldとなっていった。

In addition, Masaoka

Shiki, who advocated the innovation of waka from an early stage in his

``Utayomi ni Yofurusho'' (1898 (Meiji 31)), emphasized realism and created a

simple Manyo style of poetry. Sachio Ito, Takashi Nagatsuka, and others who

came out of this school eventually published the tanka magazine Araragi in 1908

(Meiji 41), and it became the mainstream of the poetry world. It was.

高浜虚子(たかはま・きょし)Kyoshi

Takahama

河東碧梧桐(かわひがし・へきごとう)Kawahigashi

Hekigotō

また、正岡子規(まさおか・しき)Masaoka Shikiに学んだ高浜虚子(たかはま・きょし)Kyoshi Takahamaは、1898年(明治31年)から俳句雑誌the haiku magazine『ホトトギスHototogisu』を発刊主宰し、同じく正岡子規(まさおか・しき)Masaoka Shikiの弟子disciple河東碧梧桐(かわひがし・へきごとう)Kawahigashi

Hekigotōの新派俳句the new school of haikuと俳壇the haiku worldを二分し、次第に圧倒した。

In addition, Kyoshi

Takahama, who studied under Shiki Masaoka, published the haiku magazine ``Hototogisu''

from 1898 (Meiji 31), and was also a disciple of Shiki Masaoka, Kawahigashi

Hekigoto. It divided the haiku world and the new school of haiku, and gradually

overwhelmed it.

エミール・ゾラÉmile Zola

ギ・ド・モーパッサンGuy de

Maupassant

自然主義文学(しぜんしゅぎ・ぶんがく)Naturalistic

literatureは、日露戦争(にちろ・せんそう)the Russo-Japanese Warのあと、1910年代半ば頃まで盛んとなった。

Naturalistic literature

flourished after the Russo-Japanese War until the mid-1910s.

フランスFrenchのゾラÉmile

ZolaやモーパッサンGuy de Maupassantらの影響を受け、折しも独占資本主義monopoly capitalismの発展に伴う社会的矛盾social contradictionsの激化した世情を背景に、社会の表裏the true nature of societyと人間内面の善悪the inner world of good and evilのありのままの姿を、ヒューマニズムhumanismに照らして客観的に描写しようという自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)的傾向naturalistic

tendencyが強くなった。

Influenced by French

artists such as Zola and Maupassant, and against the backdrop of the

intensifying social contradictions accompanying the development of monopoly

capitalism, this book explores the true nature of society and the inner world

of good and evil in the light of humanism. The naturalistic tendency to

describe things objectively has become stronger.

『破戒(はかい)The Broken Commandment』

島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson Shimazakiの『破戒(はかい)The Broken Commandment』はその先駆をなすものであった。

Toson Shimazaki's

``Hakkai'' was a pioneer.

田山花袋(たやま・かたい)Katai Tayama

正宗白鳥(まさむね・はくちょう)Hakuchō

Masamune

徳田秋声(とくだ・しゅうせい)Shūsei Tokuda

長塚節(ながつか・たかし)Takashi

Nagatsuka

続いて国木田独歩(くにきだ・どっぽ)Doppo Kunikidaの『牛肉と馬鈴薯(ぎゅうにく・と・ばれいしょ)Beef and Potatoes』、田山花袋(たやま・かたい)Katai Tayamaの『蒲団(ふとん)Futon(The Quilt)』・『田舎教師(いなか・きょうし)Inaka Kyōshi(Rural Teacher)』、正宗白鳥(まさむね・はくちょう)Hakuchō Masamuneの『何処へ(どこへ)Where to』、徳田秋声(とくだ・しゅうせい)Shūsei Tokudaの『足迹(あしあと)Ashiato』・『黴(かび)Kabi』・『あらくれArakure』、長塚節(ながつか・たかし)Takashi Nagatsukaの『土(つち)Tsuchi』などの作品が出た。

Next was Doppo Kunikida's

``Beef and Potatoes,'' Tayama Katai's ``Futon'' and ``Inaka Kyoushi,'' and

Masamune Shiratori. Swan's "Where to (Where to)", Shusei Tokuda's

"Ashiato", "Kabi", "Arakure", Takashi Nagatsuka's

Works such as ``Tsuchi'' were published.

島村抱月(しまむら・ほうげつ)Hogetsu

Shimamura

なかでも『春Spring』・『家Ie』などを発表した島崎藤村(しまざき・とうそん)Tōson Shimazakiと田山花袋(たやま・かたい)Katai Tayamaの活躍によって、自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)Naturalismは文壇の主流mainstream in the literary worldを占めるようになり、評論家(ひょうろんか)Critic島村抱月(しまむら・ほうげつ)Hogetsu Shimamuraらも自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)文学naturalism literature運動movementを推進した。

In particular, due to the

success of Toson Shimazaki and Hanabukuro Tayama, who published works such as

``Spring'' and ``Ie'', naturalism became mainstream in the literary world, and

critic Hogetsu Shimamura and others also considered naturalism literature.

promoted the movement.

しかし、日本Japaneseの自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)文学naturalism literatureを西欧Western Europeのそれに比べると、市民社会civil societyの未発達underdevelopmentと治安政策public security policiesの強さのために、社会問題への追求pursuing social issuesよりも私小説(ししょうせつ)I-novel・心境小説(しんきょうしょうせつ)novels of the state of mindに傾きがちであった。

However, when comparing

Japanese naturalistic literature with that of Western Europe, due to the

underdevelopment of civil society and the strength of public security policies,

it tends to lean toward personal novels and novels of the state of mind rather than

pursuing social issues.

石川啄木(いしかわ・たくぼく)Takuboku

Ishikawa

それでも自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)文学naturalism literatureの影響は各方面におよび、ロマン主義Romanticismから出た石川啄木(いしかわ・たくぼく)Takuboku Ishikawaは、歌集poetry collections『一握の砂(いちあく・の・すな)A Handful of Sand』・『悲しき玩具(かなしき・がんぐ)Sad Toys』・『呼子と口笛(よぶこ・と・くちぶえ)Yobuko and the Whistle』などによって生活詩life poetry的な歌風poetic styleを開いていった。

Still, the influence of

naturalistic literature spread to various fields, and Takuboku Ishikawa, who

came out of Romanticism, wrote poetry collections such as ``A Handful of

Sand'', ``Sad Toys'', and ``Yobuko and the Whistle''. )," he developed a

poetic style of poetry.

彼は大逆事件(たいぎゃく・じけん)the High Treason Incidentの真相the truthに関しても、鋭い関心と憤りkeen interest and indignationを示した。

He also showed keen

interest and indignation regarding the truth behind the High Treason Incident.

若山牧水(わかやま・ぼくすい)Bokusui

Wakayama

また若山牧水(わかやま・ぼくすい)Bokusui Wakayamaは近代人modern manとしての苦悩sufferingと悲哀sadnessを込めた歌を作った。

Bokusui Wakayama also wrote

songs that expressed the suffering and sadness of being a modern man.

永井荷風(ながい・かふう)Kafū Nagai

文壇the literary

worldの主流は自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)Naturalismが占めていったが、自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)文学naturalism

literatureが暗黒の面the dark sideをとかく追究したり、私小説(ししょうせつ)I-novel化の傾向を示したことに対し、幾つかの特徴のある作風distinctive stylesや作家の活躍writers' activitiesが目立つようになった。

Naturalism dominated the

literary world, but while naturalistic literature explored the dark side and

showed a tendency toward personal novels, there were some distinctive styles

and writers' activities. It became noticeable.

谷崎潤一郎(たにざき・じゅんいちろう)Jun'ichirō

Tanizaki

耽美主義(たんびしゅぎ)Aestheticism

はじめ自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)Naturalismからでた永井荷風(ながい・かふう)Kafū Nagaiは、やがて『ふらんす物語(ふらんす・ものがたり)France Monogatari』・『すみだ川(すみだがわ)Sumida River』などを書いて、文学の社会性the social aspects of literatureよりも官能美の追究pursuit of sensualityや情緒的傾向emotional tendenciesに避難seek refugeするようになり、やがて谷崎潤一郎(たにざき・じゅんいちろう)Jun'ichirō Tanizakiもこの傾向をたどった。

Kafuu Nagai, who started

out as a naturalist, eventually began to seek refuge in the pursuit of

sensuality and emotional tendencies rather than the social aspects of

literature, writing such works as ``France Monogatari'' and ``Sumida River.'' ,

and eventually Junichiro Tanizaki followed this trend.

夏目漱石(なつめ・そうせき)Natsume

Sōseki

『坊っちゃん(ぼっちゃん)Botchan』

『吾輩は猫である(わがはいはねこである)I Am a Cat』

自然主義(しぜんしゅぎ)文学naturalism literatureに表れた、人生を醜悪化make life uglyする傾向や、耽美派(たんびは)Aestheticismの官能追究pursue sensualityの傾向などのいずれにも反対Opposingして、はじめ『坊っちゃん(ぼっちゃん)Botchan』・『吾輩は猫である(わがはいは・ねこである)I Am a Cat』などロマン風な作品romantic worksを書いていた夏目漱石(なつめ・そうせき)Natsume Sōsekiは、冷静な知性calm intellectと豊富な学識rich scholarshipをもとにして、人生を傍観者的な態度で観察observed life from the sidelinesし、『虞美人草(ぐびじん・そう)Gubijinsou』・『三四郎(さんしろう)Sanshirō』・『草枕(くさまくら)Kusamakura』・『こゝろ(こころ)Kokoro』・『道草(みちくさ)Michikusa』・『明暗(めいあん)Light and Darkness』などの小説novelsや多くの文学論literary theories・随筆essays・評論criticismsなどで独特の作風unique styleを示し、高踏派(こうとうは)Parnassianism・余裕派(よゆうは)Yoyuhaなどと呼ばれた。

Opposing both the tendency

of naturalistic literature to make life ugly and the aestheticism's tendency to

pursue sensuality, he first wrote romantic works such as ``Botchan'' and ``I am

a cat.'' Based on his calm intellect and rich scholarship, Natsume Soseki

observed life from the sidelines and wrote works such as ``Gubijinsou'',

``Sanshiro'', and ``Kusamakura''. He exhibited a unique style in his novels

such as ``Kotoro'', ``Michikusa'', and ``Meikan'', as well as many literary

theories, essays, and criticisms, and was called ``Kotoha'' and ``Yakuroha.''

森鷗外(もり・おうがい)Mori Ōgai

『高瀬舟(たかせ・ぶね)Takasebune』

森鷗外(もり・おうがい)Mori Ōgaiも、文壇the

literary worldの自然主義(しぜん・しゅぎ)的傾向the naturalistic tendenciesの外に身を置き、晩年は歴史小説historical novelsに力を注ぎ、『阿部一族(あべ・いちぞく)The Abe Family』・『大塩平八郎(おおしお・へいはちろう)Ōshio Heihachirō』・『高瀬舟(たかせぶね)Takasebune』を書いた。

Mori Ogai also placed

himself outside the naturalistic tendencies of the literary world, and in his

later years devoted his efforts to historical novels, writing ``The Abe

Family'', ``Oshio Heihachiro'', and ``Takasefune''.

夏目漱石(なつめ・そうせき)Natsume

Sōseki・森鷗外(もり・おうがい)Mori Ōgaiの高踏(こうとう)的high-minded・知性尊重的respect for intelligence傾向tendenciesは、次の大正時代the Taisho eraの理想主義idealism・理知主義intellectualismに大きな影響を与えた。

Natsume Soseki and Mori

Ogai's high-minded tendencies and respect for intelligence had a great

influence on the idealism and intellectualism of the Taisho era.

巌谷小波(いわや・さざなみ)Iwaya

Sazanami

木下尚江(きのした・なおえ)Kinoshita

Naoe

このほか、児童文学children's literatureの分野では巌谷小波(いわや・さざなみ)Iwaya Sazanamiの『黄金丸(こがねまる)Koganemaru』(1891年(明治24年))があり、木下尚江(きのした・なおえ)Kinoshita Naoeの『火の柱(ひのはしら)Pillar of Fire』は社会主義文学socialist literatureの先駆として評価される。

In addition, in the field

of children's literature, there is Sazanami Iwaya's ``Koganemaru'' (1891 (Meiji

24)), and Naoe Kinoshita's ``Pillar of Fire'' is a social work. It is praised

as a pioneer of ideological literature.

小泉八雲(こいずみ・やくも)Koizumi

Yakumo(ラフカディオ・ハーンLafcadio Hearn)

『怪談(かいだん)Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things』

また『怪談(かいだん)Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things』の小泉八雲(こいずみ・やくも)Koizumi Yakumo(イギリス人British、ラフカディオ・ハーンLafcadio Hearn)も注目すべき存在で、日本を欧米に紹介introducing Japan to the Westした功績は大きい。

Yakumo Koizumi (British,

Lafcadio Hearn) from "Kaidan" is also noteworthy, and his

contribution to introducing Japan to the West was significant.

Ritorno dal pascolo

アントニオ・フォンタネージAntonio

Fontanesi

美術Art

明治初期the early

Meiji period、わが国古来の芸術品Japan's ancient works of artはとかく無視されるようになり、また廃仏毀釈(はいぶつ・きしゃく)Haibutsu kishaku(abolish

Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni)の影響もあって、仏教美術品Buddhist works of artを含む貴重な美術品valuable works of artを売り払ったり、破壊する者も少なくなかった。

In the early Meiji

period, Japan's ancient works of art began to be ignored, and due to the

influence of the Haibutsu-kishaku movement, many people sold off or destroyed

valuable works of art, including Buddhist works of art.

文明開化(ぶんめい・かいか)Civilization and Enlightenmentの風潮trendのもとで政府the governmentは、1876年(明治9年)、工部美術学校(こうぶ・びじゅつ・がっこう)the Technical Fine Arts Schoolを設け、ここに招かれたイタリア人の画家the Italian painterフォンタネージAntonio Fontanesi、彫刻家sculptorsラグーザRagusaやキヨソネChiossone、建築家architectカッペレッティCappellettiなどが、それぞれに洋風美術Western-style artの指導を行った。

Under the trend of civilization

and enlightenment, the government established the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko in 1876

(Meiji 9), and the Italian painter Fontanesi, sculptors Ragusa and Chiossone

were invited there. , architect Cappelletti, and others each taught

Western-style art.

アーネスト・フェノロサErnest

Fenollosa

このような動向のもとで、東京大学the University of Tokyoの哲学教師teach philosophyとして招かれたアメリカ人an AmericanフェノロサErnest

Fenollosaは、日本の古美術Japanese antiquityの美しさthe beautyに魅せられて高く評価し、彼の影響を強く受けた岡倉天心(おかくら・てんしん)Okakura Tenshin(岡倉覚三(おかくら・かくぞう)Okakura Kakuzō)とともに、その復興reconstructionに努めた。

In response to these

trends, Fenollosa, an American who was invited to teach philosophy at the

University of Tokyo, was fascinated by the beauty of Japanese antiquity and

highly valued it, and was strongly influenced by Okakura Tenshin. Together with

Kakuzo (Kuratenshin), he worked towards its reconstruction.

岡倉天心(おかくら・てんしん)Okakura

Tenshin(岡倉覚三(おかくら・かくぞう)Okakura Kakuzō)

折しもナショナリズムNationalism(自分たち国民、民族を重視するという考え)が台頭し、欧化主義(おうか・しゅぎ)Europeanizationに反対して国粋主義(こくすい・しゅぎ)Japanese nationalismや国粋保存(こくすいほぞん)運動national

preservation movementsが強まってきたときであったので、政府the governmentも日本美術Japanese artを奨励encourageするようになり、岡倉天心(おかくら・てんしん)Okakura Tenshinは1887年(明治20年)に東京美術学校(とうきょう・びじゅつ・がっこう)the Tokyo School of Fine Arts(現・東京芸術大学(とうきょう・げいじゅつ・だいがく)Tokyo University of the Arts)を創設foundedし、彼が校長the principalとなって日本画Japanese painting・木彫wood carving・金工metalwork・漆工lacquer workなどが教えられた。

At the same time,

nationalism was on the rise, and nationalism and national preservation

movements were becoming stronger in opposition to Europeanization, so the

government also began to encourage Japanese art, and Tenshin Okakura In 1887

(Meiji 20), he founded the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of

the Arts), where he became the principal and taught Japanese painting, wood

carving, metalwork, lacquer work, etc.

救世観音像(ぐぜ・かんのん・ぞう)statue of

Guze Kannon

また彼らは、法隆寺(ほうりゅうじ)Hōryū-jiの秘仏secret Buddhaであった夢殿(ゆめどの)Hall of Dreams救世観音像(ぐぜ・かんのん・ぞう)statue of Guze Kannonを調査investigatedした(1884年(明治17年))。

They also investigated

the Guze Kannon statue, which was a secret Buddha at Horyuji Temple (1884).

『悲母観音像(ひぼ・かんのん・ぞう)The Sad Mother Kannon』

狩野芳崖(かのう・ほうがい)Kanō Hōgai

文明開化(ぶんめい・かいか)Civilization and Enlightenmentの風潮trendのもとで、明治初期the early Meiji periodの一時は非常に流行した南画(なんが)Nangaも、前代に幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの御用絵師(ごようえし)the official painterであった狩野派(かのうは)the Kano school、大和絵(やまとえ)Yamato-e paintingsに新生面をもたらしていた土佐派(とさは)the Tosa schoolも、ともに衰えた。

Under the trend of civilization

and enlightenment, Nanga, which was once very popular in the early Meiji

period, as well as the Kano school, which was the official painter of the

shogunate in the previous era, and the Tosa school, which had brought a new

aspect to Yamato-e, all declined.

Folding screen Dragon and

tiger

『龍虎図(りゅうこず)Dragon and Tiger』

橋本雅邦(はしもと・がほう)Hashimoto

Gahō

Folding screen Dragon and

tiger

『龍虎図(りゅうこず)Dragon and Tiger』

橋本雅邦(はしもと・がほう)Hashimoto

Gahō

このような日本画の衰勢This decline in Japanese paintingは、『悲母観音像(ひぼ・かんのん・ぞう)The Sad Mother Kannon』を描いてフェノロサErnest Fenollosaに才能を見出された狩野芳崖(かのう・ほうがい)Kanō Hōgaiや、『龍虎図(りゅうこず)Dragon and Tiger』を描いた橋本雅邦(はしもと・がほう)Hashimoto Gahōらの活躍と、東京美術学校(とうきょう・びじゅつ・がっこう)the Tokyo School of Fine Arts(現・東京芸術大学(とうきょう・げいじゅつ・だいがく)Tokyo University of the Arts)の創立によって復興の機をつかんだ。

This decline in Japanese

painting is due to Kano Hogai, whose talent was discovered by Fenollosa after

painting ``The Sad Mother Kannon (Hibo),'' and Hashimoto Gaho, who painted

``Dragon and Tiger.'' Thanks to the successes of the school and the

establishment of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (currently Tokyo University of

the Arts), an opportunity for revival was seized.

熊野観花(くまの・かんか)Kumano flower

viewing

下村観山(しもむら・かんざん)Kanzan

Shimomura

屈原(くつげん)Qu Yuan

横山大観(よこやま・たいかん)Yokoyama

Taikan

黒き猫Black Cat

菱田春草(ひしだ・しゅんそう)Hishida

Shunsō

虎の写生tiger sketch

川端玉章(かわばた・ぎょくしょう)Kawabata

Gyokushō

班猫(はんびょう)Tabby Cat

竹内栖鳳(たけうち・せいほう)Takeuchi

Seihō

そして、岡倉天心(おかくら・てんしん)Okakura Tenshinは、1898年(明治31年)に東京美術学校(とうきょう・びじゅつ・がっこう)the Tokyo School of Fine Arts長post as directorを辞するとともに、日本美術院(にほん・びじゅついん)Nihon Bijutsuinを創立したが、これに、狩野芳崖(かのう・ほうがい)Kanō Hōgai・橋本雅邦(はしもと・がほう)Hashimoto Gahōの門から出た下村観山(しもむら・かんざん)Kanzan Shimomura・横山大観(よこやま・たいかん)Yokoyama Taikan・菱田春草(ひしだ・しゅんそう)Hishida Shunsō、四条派(しじょうは)the Shijo schoolから出た川端玉章(かわばた・ぎょくしょう)Kawabata Gyokushō、京都Kyotoの竹内栖鳳(たけうち・せいほう)Takeuchi Seihōらが参加し、革新的な活動innovative activitiesを続けた。

In 1898, Tenshin Okakura

(Kakuzo) resigned from his post as director of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts

and founded the Japan Art Institute. Shimomura Kanzan, Yokoyama Taikan, and Hishida

Shunso from Gaho's gate, Kawabata Gyokusho from the Shijo school, and Takeuchi

Seiho from Kyoto. ) participated and continued innovative activities.

濁醪療渇黄葉村店(だくろう・りょうかつ・こうよう・そんてん)Quenching Thirst with Raw Sake at a Shop in the Autumn Countryside

小山正太郎(こやま・しょうたろう)Koyama Shōtarō

収穫Harvest

浅井忠(あさい・ちゅう)Asai Chū

鮭Salmon

高橋由一(たかはし・ゆいち)Takahashi Yuichi

洋画(ようが)Western paintingsは、工部大学校(こうぶ・だいがっこう)Imperial College of Engineeringの外国人教師foreign teachersフォンタネージAntonio FontanesiやジョヴァンニAcchile San Giovanniなどが影響を与え、はじめ小山正太郎(こやま・しょうたろう)Koyama Shōtarō・浅井忠(あさい・ちゅう)Asai Chū・高橋由一(たかはし・ゆいち)Takahashi Yuichiらが出たが、復興した日本画Japanese paintingの隆盛に圧せられた。

Western paintings were

influenced by foreign teachers such as Fontanesi and Giovanni at the College of

Engineering, and were first created by Shotaro Koyama, Tadashi Asai, and Yuichi

Takahashi. He was overwhelmed by the prosperity of the revived Japanese

painting.

この間にも、浅井忠(あさい・ちゅう)Asai Chūや高橋由一(たかはし・ゆいち)Takahashi Yuichiは私塾private schoolsを開いて弟子の養成train studentsに努め、かつ優れた作品outstanding worksを発表した。

During this period,

Tadashi Asai and Yuichi Takahashi opened private schools to train students and

published outstanding works.

湖畔(こはん)Lakeside

黒田清輝(くろだ・せいき)Kuroda Seiki

秋Autumn

久米桂一郎(くめ・けいいちろう)Kume

Keiichiro

海の幸Fruits of the

Sea

青木繁(あおき・しげる)Shigeru Aoki

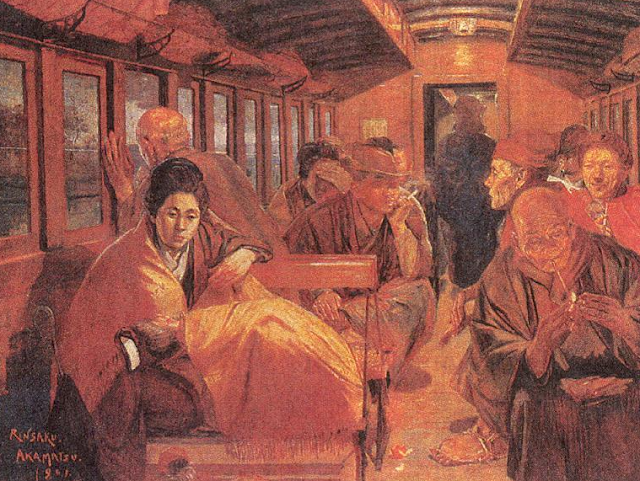

洋画(ようが)Western paintingsの隆盛の機となったのは、フランスFranceに留学studied abroadしていた黒田清輝(くろだ・せいき)Kuroda Seiki・久米桂一郎(くめ・けいいちろう)Kume

Keiichiroが帰国して外光派(がいこうは)Pleinairismeと呼ばれる清新な印象派(いんしょうは)的画風impressionist style paintingを伝えたことと、洋画壇the Western art worldに流星meteorの如く現れた青木繁(あおき・しげる)Shigeru Aokiのロマン的作風the romantic painting styleであった。

The rise of Western

painting was triggered by Seiki Kuroda and Keiichiro Kume, who had studied

abroad in France, and returned to Japan to create a fresh impressionist style

called plein air painting. It conveyed the painting style and the romantic

style of Shigeru Aoki, who appeared like a meteor in the Western art world.

婦人像Portrait of a

Lady

岡田三郎助(おかだ・さぶろうすけ)Okada

Saburōsuke

黒扇(くろおうぎ)Black Fan

藤島武二(ふじしま・たけじ)Fujishima

Takeji

そして1896年(明治29年)には東京美術学校(とうきょうびじゅつがっこう)the Tokyo School of Fine Artsに西洋画科Department of Western Paintingも設けられ、黒田清輝(くろだ・せいき)Kuroda Seiki・久米桂一郎(くめけいいちろう)Kume Keiichiroらが教授professorsになり、その門から岡田三郎助(おかだ・さぶろうすけ)Okada Saburōsuke・藤島武二(ふじしま・たけじ)Fujishima Takeji・和田英作(わだえいさく)Wada Eisakuらが出た。

In 1896 (Meiji 29), a

Department of Western Painting was established at the Tokyo School of Fine

Arts, with Seiki Kuroda and Keiichiro Kume becoming professors. Takeji), Eisaku

Wada, and others appeared.

渡頭の夕暮(ととうの・ゆうぐれ)Evening at

the Ferry Crossing

和田英作(わだ・えいさく)Wada Eisaku

彼らは黒田清輝(くろだ・せいき)Kuroda Seiki・久米桂一郎(くめ・けいいちろう)Kume Keiichiroを中心として、1896年(明治29年)に白馬会(はくば・かい)Hakuba-kai(White Horse Society)(~1911年(明治44年))を組織し、1889年(明治22年)に浅井忠(あさい・ちゅう)Asai Chūらが組織した、脂派(やには)the Yaniha schoolと呼ばれた明治美術会(めいじ・びしゅつかい)the Meiji Bijutsu Kai(~1901年(明治34年))派の写実主義(しゃじつ・しゅぎ)Realismに対して、明快な画風clear style of paintingを特色とした。

They organized the

Hakuba-kai (until 1911) in 1896 (Meiji 29), centered on Kuroda Seiki and Kume

Keiichiro, and Asai Tadashi in 1889 (Meiji 22). In contrast to the realism of

the Meiji Bijutsu Kai (~1901) school, known as the Yahana school, which was organized

by the group, it was characterized by a clear style of painting.

南風(なんぷう)south wind

和田三造(わだ・さんぞう)Sanzo Wada

やがて小山正太郎(こやま・しょうたろう)Koyama Shōtarō・浅井忠(あさい・ちゅう)Asai Chū門下が、1901年(明治34年)に太平洋画会(たいへいよう・がかい)the Pacific Painting Associationを結成し、白馬会(はくば・かい)Hakuba-kai(White Horse Society)と並んで二大洋画団体the two major Western painting groupsとなった。

Eventually, Shotaro

Koyama and Tadashi Asai's students formed the Pacific Painting Association in

1901 (Meiji 34), which became one of the two major Western painting groups

along with the Hakubakai.

神湊(こうの・みなと)Kounominato

坂本繁二郎(さかもと・はんじろう)Sakamoto

Hanjirō

1907年(明治40年)からは、諸会派を統合して文部省美術展覧会(もんぶしょう・びじゅつ・てんらんかい)the Ministry of Education Art Exhibition(文展(ぶんてん)Bunten)が開かれ、そのなかから和田三造(わだ・さんぞう)Sanzo Wada(『南風(なんぷう)south wind』)・坂本繁二郎(さかもと・はんじろう)Sakamoto Hanjirōらが出た。

From 1907 (Meiji 40), the

Ministry of Education Art Exhibition (Bunten) was held by merging various

groups, and among them Sanzo Wada (``Nanfu'') and Hanjiro Sakamoto (Hanjiro

Sakamoto) appeared.

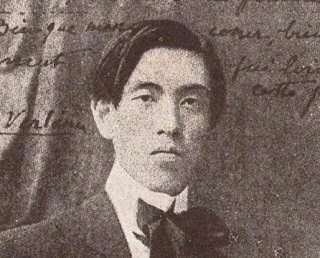

夜汽車(よぎしゃ)Night Train

赤松麟作(あかまつ・りんさく)Akamatsu

Rinsaku

また『夜汽車(よぎしゃ)Night Train』を発表した赤松麟作(あかまつ・りんさく)Akamatsu Rinsakuは、大阪に研究所を設けて、後進の指導に当たりながら優れた作品を発表した。

In addition, Rinsaku

Akamatsu, who published ``Night Train,'' set up a research institute in Osaka

and published excellent works while teaching his successors.

日本婦人Japanese

Woman

ラグーザVincenzo

Ragusa

明治天皇(めいじ・てんのう)Emperor Meiji

キヨソネEdoardo

Chiossone

ラグーザVincenzo

Ragusaによって塑像plastic statues・大理石彫刻marble carvings・建築装飾architectural decorationsなどの洋風技術Western techniquesが伝えられ、またキヨソネEdoardo Chiossoneは、銅版彫刻copperplate engravingとその印刷技術printing techniquesを教え、紙幣の画paintings for banknotesも考案した。

Ragusa introduced Western

techniques such as plastic statues, marble carvings, and architectural

decorations, while Quiosone also taught copperplate engraving and printing

techniques, and invented paintings for banknotes.

老猿(ろうえん)old monkey

高村光雲(たかむら・こううん)Takamura Kōun

ジェンナー像Edward Jenner

米原雲海(よねはら・うんかい)Yonehara

Unkai

平櫛田中(ひらくし・でんちゅう)Hirakushi

Denchū

Nichiren in Fukuoka

竹内久一(たけうち・きゅういち)Takeuchi

Kyūichi

東京美術学校(とうきょう・びじゅつ・がっこう)the Tokyo

School of Fine Artsにも1898年(明治31年)から彫塑科sculpture departmentがおかれ、伝統的な木彫りtraditional wood carvingに高村光雲(たかむら・こううん)Takamura Kōunが指導的な地位leading positionを占め、米原雲海(よねはら・うんかい)Yonehara Unkai・平櫛田中(ひらくし・でんちゅう)Hirakushi Denchūらを育て、竹内久一(たけうち・きゅういち)Takeuchi Kyūichiも独自の写実的表現法his own unique method of realistic expressionを案出した。

Tokyo School of Fine Arts

also had a sculpture department in 1898 (Meiji 31), with Koun Takamura holding

a leading position in traditional wood carving, and Unkai Yonehara and

Hirakushi Denchu. Kyuichi Takeuchi also devised his own unique method of

realistic expression.

北白川宮像Prinz

Kitashirakawa

新海竹太郎(しんかい・たけたろう)Shinkai Taketarō

滝廉太郎(たき・れんたろう)Rentarō Taki

朝倉文夫(あさくら・ふみお)Fumio Asakura

しかし、日露戦争(にちろ・せんそう)the Russo-Japanese War前後頃から西洋近代彫刻Western modern sculptureの作風がしきりに紹介されるようになり、新海竹太郎(しんかい・たけたろう)Shinkai Taketarōは、ドイツのロマン主義的作風the German Romantic styleをもとにした作品worksを作りつつ、朝倉文夫(あさくら・ふみお)Fumio Asakuraら後進を指導した。

However, around the time

of the Russo-Japanese War, the style of Western modern sculpture began to be

frequently introduced, and Taketaro Shinkai created works based on the German

Romantic style. ) and others.

He mentored younger

players such as Fumio Asakura.

坑夫The Miner

荻原守衛(おぎわら・もりえ)Morie Ogiwara

このような彫刻界the world of sculptureに新紀元a new eraを画したのは、フランスFranceのロダンRodinの下で学んだ荻原守衛(おぎわら・もりえ)Morie Ogiwaraの帰国(1908年(明治41年))であり、彼は『女Onna』・『文覚(もんがく)Mongaku』・『坑夫The Miner』などの傑作masterpiecesを残した。

What marked a new era in

the world of sculpture was the return of Morie Ogiwara (1908), who had studied

under Rodin in France, and he created works such as ``Onna'' and ``Onna''. He

left behind masterpieces such as ``Mongaku'' and ``Miner.''

造幣局(ぞうへいきょく)Japan Mint

ウォートルスThomas Waters

政府the

governmentは、洋風建築Western-style architectureの技術者を養成train engineersするため、明治初期the early Meiji periodには多くの外国人建築家foreign architectsを招いた。

In the early Meiji

period, the government invited many foreign architects to train engineers for

Western-style architecture.

鹿鳴館(ろくめいかん)Rokumeikan(Banqueting House)

コンドルJosiah Conder

遊就館(ゆうしゅうかん)Yūshūkan

カッペレッティGiovanni Cappelletti

1868年(明治1年)に来日して、大阪造幣寮the Osaka Mint House・英国公使館the British Legationなどをルネサンス式Renaissanceや古典様式classical styleの煉瓦造brick buildingsでつくったイギリス人an EnglishmanウォートルスThomas Waters、上野博物館Ueno

Museum(東京国立博物館Tokyo National Museumの前身)・鹿鳴館(ろくめいかん)Rokumeikan・ニコライ堂Nicholas Hallなどを設計したイギリス人an EnglishmanコンドルJosiah Conder、参謀本部Imperial

Japanese Army General Staff Office(イタリア・ルネサンス式Italian Renaissance style)・遊就館(ゆうしゅうかん)Yūshūkan(ロマネスク様式Romanesque style)を建てたイタリア人an ItalianカッペレッティGiovanni Cappellettiなどが有名である。

Wartrus, an Englishman

who came to Japan in 1868 (Meiji 1) and built the Osaka Mint House and the British

Legation in Renaissance and classical style brick buildings; Famous examples

include Conder, an Englishman who designed the Nicholas Hall, and Cappelletti,

an Italian who built the General Staff Headquarters (Italian Renaissance style)

and Yushukan (Romanesque style).

東京駅Tokyo Station

辰野金吾(たつの・きんご)Tatsuno Kingo

赤坂離宮(あかさか・りきゅう)Akasaka

Palace(現在の迎賓館(げいひんかん)State Guest House)

片山東熊(かたやま・とうくま)Katayama

Tōkuma

そして、コンドルJosiah Conderの指導を受けた辰野金吾(たつの・きんご)Tatsuno Kingoは日本銀行本店the Bank of Japan's head office・東京駅Tokyo Stationを、片山東熊(かたやま・とうくま)Katayama Tōkumaはヴェルサイユ宮殿the Palace of Versaillesを模して赤坂離宮(あかさかり・きゅう)Akasaka Palace(現在の迎賓館(げいひんかん)State Guest House)を設計した。

Kingo Tatsuno, who

received Condor's guidance, built the Bank of Japan's head office and Tokyo

Station, and Tokuma Katayama built the Akasaka Imperial Villa (currently the

State Guest House) after the Palace of Versailles. ) was designed.

軍楽隊military

bands

音楽Music・演劇Theater

西洋音楽Western musicはすでに幕末the

end of the Edo periodの西洋兵制Western military systemとともに採用されており、明治the Meiji period以後にも陸海軍the Army and Navyに軍楽隊military bandsが組織され、西洋音楽Western musicの習得と普及に大きな影響力をもち、わが国初のオーケストラ演奏orchestral performanceが、1905年(明治38年)、陸・海軍軍楽隊the Army and Navy military bandsによって行われた。

In other words, Western

music had already been adopted along with the Western military system at the

end of the Edo period, and even after the Meiji period military bands were

organized in the Army and Navy, which had a great influence on the acquisition

and spread of Western music, and Japan's first orchestral performance was held in

1905. (Meiji 38), performed by the Army and Navy military bands.

伊沢修二(いざわ・しゅうじ)Izawa Shūji

そのような情勢のもとで、伊沢修二(いざわ・しゅうじ)Izawa Shūjiは、近代的な音楽教育modern music educationの重要性を説いたので、明治政府the Meiji governmentは、1879年(明治12年)に音楽取調掛(おんがく・とりしらべ・がかり)the music investigation department(東京芸術大学Tokyo University of the Arts音楽学部music departmentの前身)を設け、一部の反対を押し切って洋楽Western musicを学校教育school educationに取り入れ、小学唱歌elementary school songsの制定に着手した。

Under such circumstances,

Shuji Izawa emphasized the importance of modern music education, and in 1879

(Meiji 12) the Meiji government established the Music Inquiry Committee (Tokyo

Arts Center). The school established a university music department (the

predecessor of the university's music department), incorporated Western music

into school education despite some opposition, and began establishing

elementary school songs.

滝廉太郎(たき・れんたろう)Rentarō Taki

『荒城の月(こうじょう・の・つき)Kōjō no Tsuki』

ついで1887年(明治20年)には音楽取調掛(おんがく・とりしらべ・がかり)the music investigation departmentを拡充して、東京音楽学校(とうきょう・おんがく・がっこう)the Tokyo School of Music(東京芸術大学Tokyo University of the Arts音楽学部music departmentの前身)として設立されたが、その卒業生である滝廉太郎(たき・れんたろう)Rentarō Takiは、『荒城の月(こうじょう・の・つき)Kōjō no Tsuki』・『箱根八里(はこね・はちり)Hakone Hachiri』のように日本人らしい独創性のある名曲を創作した。

Then, in 1887 (Meiji 20),

the music investigation department was expanded and the Tokyo School of Music

(predecessor of the Faculty of Music, Tokyo University of the Arts) was established,

and its graduate, Rentaro Taki, He created masterpieces with originality typical

of Japanese people, such as ``Kojo no Tsuki'' and ``Hakone Hachiri''.

河竹黙阿弥(かわたけ・もくあみ)Kawatake

Mokuami

幕末the end of

the Edo periodから明治the Meiji periodにかけて河竹黙阿弥(かわたけ・もくあみ)Kawatake Mokuamiが出て、散切物(ざんぎりもの)zangirimono・活歴物(かつれき・もの)katsurekimonoと称する多くの新作歌舞伎new Kabuki playsを書いたが、自由民権運動the freedom and civil rights movementが盛んになると、演劇界the

theater worldでも歌舞伎kabukiより壮士芝居(そうし・しばい)sōshi plays・書生芝居(しょせい・しばい)shosei playsが目立つようになった。

From the end of the Edo

period to the Meiji period, Mokuami Kawatake appeared and wrote many new Kabuki

plays called zangirimono and katsurekimono, but the freedom and civil rights

movement was flourishing. Around this time, even in the theater world, sōshi

plays and shosei plays became more prominent than kabuki.

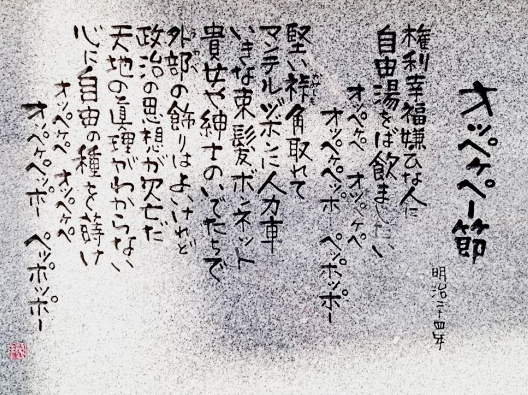

角藤定憲(すどう・さだのり)Sudo Sadanori

川上音二郎(かわかみ・おとじろう)Kawakami

Otojirō

川上音二郎(かわかみ・おとじろう)Kawakami

Otojirō

伊井蓉峰(いい・ようほう)Ii Yōhō

それは、自由民権運動the Freedom and People's Rights Movementの政治的宣伝劇political propaganda playから現実写実劇real-life dramaとして発展し、角藤定憲(すどう・さだのり)Sudo Sadanoriや川上音二郎(かわかみ・おとじろう)Kawakami Otojirōらが草案したものであったが、これが伊井蓉峰(いい・ようほう)Ii Yōhōらによって次第に歌舞伎Kabukiに対する新派劇(しんぱげき)a new school of theaterとして発展させられていった。

It evolved from a

political propaganda play for the Freedom and People's Rights Movement to a

real-life drama, and was drafted by Sadanori Kakudo and Otojiro Kawakami, but

this was the work of Yomine Ii. It was gradually developed by Iiyohou and

others as a new school of theater to Kabuki.

福地源一郎(ふくち・げんいちろう)Fukuchi

Gen'ichirō(福地桜痴(ふくち・おうち)Fukuchi Ōchi)

九代目市川団十郎(くだいめ・いちかわ・だんじゅうろう)Ichikawa Danjūrō IX

五代目尾上菊五郎(ごだいめ・おのえ・きくごろう)Onoe Kikugorō V

初代市川左団次(しょだい・いちかわ・さだんじ)Ichikawa Sadanji

I

しかし歌舞伎界the Kabuki worldでも演劇改良運動a movement to improve theaterが起こり、九代目市川団十郎(くだいめ・いちかわ・だんじゅうろう)Ichikawa Danjūrō IXは写実的演技realistic actingを主張し、福地桜痴(ふくち・おうち)Fukuchi Ōchiが書いた活歴物(かつれき・もの)Katsurekimonoの脚本によって時代物historical playsの上演に新分野a new fieldを開拓し、五代目尾上菊五郎(ごだいめ・おのえ・きくごろう)Onoe Kikugorō V・初代市川左団次(しょだい・いちかわ・さだんじ)Ichikawa Sadanji Iらとともに、1889年(明治22年)に開かれた歌舞伎座the

Kabuki-za theaterを中心に、国粋主義(こくすい・しゅぎ)Japanese

nationalismの台頭the

riseと資本主義の発展the development of capitalismにともなう経済界の活気the vitality of the economic worldに乗じて、歌舞伎Kabukiの一大隆盛期a

period of great prosperityを築いた。

However, a movement to

improve theater took place in the Kabuki world, and Danjuro Ichikawa, the 9th

generation, advocated realistic acting, and based on the script for