日本史29 Japanese history 29

学問の発達 Academic Development

大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしま・せいどう)Yushima Seidō)

貝原益軒(かいばら・えきけん)Kaibara Ekiken

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighter

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighter

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighterは第二次世界大戦World War II時の日本陸軍Imperial Japanese Armyの戦闘機Fighter aircraftである。

The Type 5 fighter plane

(Goshiki) was a fighter plane of the Japanese Army during World War II.

開発Development・製造Manufacturingは川崎航空機Kawasaki

Aircraft Industries、設計主務者the chief designerは土井武夫(どい・たけお)Takeo Doi。

It was developed and

manufactured by Kawasaki Aircraft, and the chief designer was Takeo Doi.

帝国陸軍Imperial

Japanese Army最後の制式戦闘機the last

formal fighterとされる軍用機Military aircraftである。

It is a military aircraft

that is said to be the last formal fighter of the Imperial Army.

三式戦闘機(さんしき・せんとうき)「飛燕(ひえん)」 Type 3 Fighter Hien (flying swallow)

製作不良・整備困難などから液冷エンジンLiquid-cooled Aircraft engine、ハ140 Kawasaki Ha140の供給不足に陥り、機体のみが余っていた三式戦闘機(さんしき・せんとうき)二型Type 3

Fighter Model 2に急遽空冷エンジンAir-cooled Aircraft engine、ハ112II the Ha-112II(金星(きんせい)Mitsubishi Kinsei)を搭載し戦力化したものであるが、時間的猶予の無い急な設計であるにもかかわらず意外な高性能を発揮、整備性や信頼性も比較にならないほど向上した。

Due to manufacturing

defects and maintenance difficulties, the liquid-cooled engine, Ha-140, was in

short supply, and the Type 3 fighter jet, which had only one left over, was

hurriedly equipped with an air-cooled engine, the Ha-112II (Kinsei), to make it

a viable fighter. However, despite the sudden design with no time constraints,

it achieved unexpected high performance, and its maintainability and

reliability improved beyond comparison.

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighter

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighterは第二次世界大戦World War II末期に登場し、また生産数も少ないために実戦での活躍は少ないが、末期の日本陸軍Imperial

Japanese Armyにとり相応の戦力となった。

The Type 5 fighter

appeared at the end of World War II, and although it was produced in small numbers

and saw little active use in actual combat, it became a force suitable for the

Japanese Army in its final stages.

離昇出力は1500馬力と四式戦闘機(よんしき・せんとうき)「疾風(はやて)」 Type 4 Fighter Hayate

(Gale)には及ばないものの空戦能力・信頼性とも当時の操縦士には好評で、アメリカ軍の新鋭戦闘機the latest American fighter aircraftsと十分に渡り合えたと証言する元操縦士も多い。

Although its takeoff

output was 1,500 horsepower, which was not as high as the Type 4 fighter

"Shippu," its air combat ability and reliability were well received

by pilots at the time, and a former pilot testifies that it was able to compete

with the latest American fighter aircrafts. There are also many.

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighter

ボーイングB-29スーパーフォートレス Boeing B-29

Superfortress

P-51マスタング North American P-51 Mustang

グラマンF6Fヘルキャット Grumman F6F

Hellcat

1945年(昭和20年)6月5日、五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5 Fighterの13機はB-29爆撃機Boeing B-29 Superfortressを攻撃した。

On June 5, 1945, 13 Type

5 fighters attacked a B-29 bomber.

1945年(昭和20年)7月16日、24機の五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5 Fighterが、硫黄島Iwo Jimaを出撃したアメリカ陸軍航空軍US Army Air ForcesのP-51マスタングNorth

American P-51 Mustang 96機と三重県松阪市上空にて交戦した。

On July 16, 1945, 24 Type

5 fighter planes engaged 96 P-51 Mustangs of the U.S. Army Air Forces that had

departed from Iwo Jima over Matsusaka City, Mie Prefecture.

1945年(昭和20年)7月25日、滋賀県神崎郡(現・東近江市)付近上空で、アメリカ海軍US Navyの18機のF6FヘルキャットGrumman F6F

Hellcatに対して、五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5 Fighterの16機で挑んだ。

On July 25, 1945, 16 Type

5 fighters took on 18 U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats in the skies near Kanzaki County,

Shiga Prefecture (now Higashiomi City).

1945年(昭和20年)7月28日には18機の五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5 Fighterで24機のF6FヘルキャットGrumman F6F

Hellcatと交戦した。

On July 28, 1945, 18 Type

5 fighters engaged 24 F6F Hellcats.

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighter

P-51マスタング North American P-51 Mustang

五式戦闘機(ごしき・せんとうき)Type 5

Fighterは1500馬力クラスであり、アメリカUSAのP-51マスタングNorth American P-51 Mustang(1700馬力クラス)に及ばぬまでも接近する出力性能は持っていた。

The Type 5 fighter was in

the 1,500 horsepower class, and had an output performance that came close to,

if not surpassed, that of the American P-51 Mustang (1,700 horsepower class).

しかしながらP-51マスタングNorth American P-51 Mustangは空気力学的洗練により最高で700km/h以上の速度性能を発揮していた。

However, the P-51

Mustang's aerodynamic sophistication allowed it to reach speeds of up to 700

km/h.

大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしませいどう)Yushima Seidō)

第8章 Chapter 8

幕藩体制の展開

Development of the Shogunate

system

第3節 Section 3

学問の発達Academic Development

朱熹(しゅき)Zhu Xi

朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianism

文治政治(ぶんち・せいじ)Civilized Politicsの展開the developmentに従い、儒学(じゅがく)Confucianismが近世封建社会early modern feudal societyの精神を支配dominated the spiritする思想the ideology、すなわち幕藩体制(ばくはん・たいせい)the Shogunate and feudal systemにそった政治思想political philosophyとして発達した。

Along with the

development of Bunji politics, Confucianism developed as a political philosophy

in line with the ideology that dominated the spirit of early modern feudal

society, that is, the Shogunate and feudal system.

朱子学(しゅしがく)Shushigaku(Cheng–Zhu school)

なかでも、大義名分論(たいぎ・めいぶん・ろん)the theory of just causeに基づいて身分的秩序social orderを強調する朱子学(しゅしがく)Shushigakuは、既に鎌倉・室町時代the Kamakura and Muromachi periodsから学ばれていたが、江戸時代the

Edo periodに入り、林家(りんけ)the Rinke familyが幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateに登用されたことから権力と結びつきassociated with power、官学(かんがく)government and academic institutionの扱いを受け、幕藩体制(ばくはん・たいせい)the Shogunate and feudal systemの思想的支柱the ideological pillarとなった。

Among these, Shushigaku

(Shushigaku), which emphasizes social order based on the theory of just cause,

had already been studied since the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, but in the

Edo period, the Rinke family was appointed to the Shogunate. Because of this,

it was associated with power, was treated as a government and academic

institution, and became the ideological pillar of the Shogunate and feudal

system.

王陽明(おう・ようめい)Wang Yangming

しかし、朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismの形式主義the formalismに対抗して、中国China(明(みん)the Ming Dynasty)の王陽明(おう・ようめい)Wang Yangmingの流れをくむ陽明学(ようめいがく)the Yomeigaku schoolや、古典への復帰return to the classicsを説く古学派(こがくは)the Old Schoolも現れた。

However, in opposition to

the formalism of Neo-Confucianism, the Yomeigaku school, descended from Wang

Yangming of China (Ming Dynasty), and the Old School, which advocated a return

to the classics, also emerged.

徳川家康(とくがわ・いえやす)Tokugawa Ieyasu

藤原惺窩(ふじわら・せいか)Fujiwara

Seika(1561~1619)

林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razan(道春(どうしゅん)Doshun)

徳川家康(とくがわ・いえやす)Tokugawa Ieyasuは儒仏の分離the

separation of Confucianism and Buddhismを求め、藤原惺窩(ふじわら・せいか)Fujiwara Seikaの門人disciple林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razanを登用した。

Tokugawa Ieyasu sought

the separation of Confucianism and Buddhism, and appointed Hayashi Razan, a

disciple of Fujiwara Seika.

徳川家綱(とくがわ・いえつな)Tokugawa Ietsuna(在職1651年~1680年)

4代将軍the 4th shogun

林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razanは徳川家康(とくがわ・いえやす)Tokugawa Ieyasuから徳川家綱(とくがわ・いえつな)Tokugawa Ietsunaに至る4代の将軍four

generations of shogunsに仕え、幕府創業期during the founding of the shogunateの文教(ぶんきょう)政策the educational policyの確立に貢献した。

Hayashi Razan served four

generations of shoguns, from Tokugawa Ieyasu to Tokugawa Ietsuna, and

contributed to the establishment of the educational policy during the founding

of the shogunate.

林信篤(はやし・のぶあつ)Hayashi

Nobutatsu(鳳岡(ほうこう)Hōkō)

林家(りんけ)the Rinke familyはその後、林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razanの子son林鵞峯(はやし・がほう)Hayashi Gahō(春斎(しゅんさい)Shunsai)や孫grandson林信篤(はやし・のぶあつ)Hayashi

Nobutatsu(鳳岡(ほうこう)Hōkō)など、代々幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの儒官(じゅかん)Confucian officialに起用され文教(ぶんきょう)educationを司った。

The Rinke family was

subsequently appointed as a Confucian official in the shogunate for

generations, including Hayashi Razan's son Hayashi Gahou (Shunsai) and his

grandson Hayashi Houkou (Nobuatsu). He was in charge of education.

徳川綱吉(とくがわ・つなよし)Tokugawa Tsunayoshi(在職1680~1709)

5代将軍the 5th shogun

大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしま・せいどう)Yushima Seidō)

大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしませいどう)Yushima Seidō)

好学well-educatedの5代将軍the 5th

shogun徳川綱吉(とくがわ・つなよし)Tokugawa Tsunayoshi(在職1680~1709)は湯島(ゆしま)Yushimaに大成殿(たいせいでん)Taiseiden(湯島聖堂(ゆしま・せいどう)Yushima Seidō)を建て、ここに上野(うえの)Ueno忍ヶ岡(しのぶがおか)Shinobugaokaの林家(りんけ)the Rinke familyの孔子廟(こうしびょう)The temple of Confuciusを移して朱子学の殿堂the temple of Neo-Confucianismとし、さらに林家(りんけ)the Rinke familyの私塾the private schoolを移して学問所(がくもんじょ)academic institutionとした(のちに昌平坂学問所(しょうへいざか・がくもんしょ)Shohei-zaka Gakumonshoと呼ばれる)。

The fifth shogun,

Tsunayoshi Tokugawa (1680-1709), a well-educated shogun, built Taiseiden

(Yushima Seido) in Yushima, where the Rinke family of Ueno Shinogaoka was

built. The temple of Confucius was moved and became the temple of

Neo-Confucianism, and the private school of the Rinke family was also moved and

became an academic institution (later called Shohei-zaka Gakumonsho).

また林信篤(はやし・のぶあつ)Hayashi Nobutatsu(鳳岡(ほうこう)Hōkō)を大学頭(だいがく・の・かみ)Daigaku no Kami(head

of the university)に任じ、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの教学(きょうがく)educationを司らせた。

He also appointed Hayashi

Houkou as head of the university and put him in charge of education for the

shogunate.

松永尺五(まつなが・せきご)Matsunaga

Sekigo

石川丈山(いしかわ・じょうざん)Ishikawa

Jōzan

朱子学派Neo-Confucian school

① 京学派(きょうがくは)Kyoto school

藤原惺窩(ふじわら・せいか)Fujiwara Seikaを祖ancestorとし、林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razanをはじめ、町儒者Confucianとして京都の私塾private schoolで門人disciplesを養成trainedした松永尺五(まつなが・せきご)Matsunaga Sekigoや、石川丈山(いしかわ・じょうざん)Ishikawa Jōzanがあった。

His ancestor was Fujiwara

Seika, Hayashi Razan, Matsunaga Sekigo, who trained his disciples at a private

school in Kyoto as a Confucian, and Ishikawa Jozan. Ishikawa Jozan).

木下順庵(きのした・じゅんあん)Kinoshita

Jun'an

新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakuseki(1657年~1725年)

室鳩巣(むろ・きゅうそう)Muro Kyūsō(1658~1734)

雨森芳洲(あめのもり・ほうしゅう)Amenomori Hoshu

三宅観瀾(みやけ・かんらん)Miyake Kanran

祇園南海(ぎおん・なんかい)Gion Nankai

松永尺五(まつなが・せきご)Matsunaga

Sekigoの門弟discipleの木下順庵(きのした・じゅんあん)Kinoshita Jun'anは金沢(かなざわ)Kanazawaの前田家(まえだけ)the Maeda familyに用いられ、のち徳川綱吉(とくがわ・つなよし)Tokugawa Tsunayoshiの侍講(じこう)a lecturerとなり、木門(ぼくもん)Bokumonの祖foundersとして、新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakuseki・室鳩巣(むろ・きゅうそう)Muro Kyūsō・雨森芳洲(あめのもり・ほうしゅう)Amenomori

Hoshu・三宅観瀾(みやけ・かんらん)Miyake Kanran・祇園南海(ぎおん・なんかい)Gion Nankaiらの優れた人材excellent human resourcesを輩出した。

Kinoshita Junan, a

disciple of Matsunaga Sekigo, was used by the Maeda family in Kanazawa, and

later became a samurai of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, and became Bokumon. Its founders

include Arai Hakuseki, Murokyusou, Amenomori Hoshu, Miyake Kanran, and Gion

Nankai. It has produced excellent human resources.

野中兼山(のなか・けんざん)Nonaka Kenzan

山崎闇斎(やまざき・あんさい)Yamazaki Ansai(1618~1682)

②戦国時代the Sengoku periodに土佐(とさ)Tosa Province(高知県(こうちけん)Kōchi

Prefecture)の南村梅軒(みなみむら・ばいけん)Minamimura Baikenが興したfounded海南学派(かいなんがくは)Kainan school(南学派(なんがくは)Nangaku school)は、その門弟disciple谷時中(たに・じちゅう)Tani Jichuによって大成fruitionされた。

The Kainan school (Nan

school) was founded by Baiken Minamimura of Tosa during the Sengoku period, and

was brought to fruition by his disciple Jichu Tani.

谷時中(じちゅう)Tani Jichuの門人discipleで土佐藩家老chief

retainer of the Tosa domainの野中兼山(のなか・けんざん)Nonaka Kenzanは、藩政改革reforming

the domain's administrationに手腕をふるい、また門人disciple山崎闇斎(やまざき・あんさい)Yamazaki Ansai(1618~1682)は、朱子学Neo-Confucianismをはじめ諸家various

familiesの神道説the Shinto theoriesを集大成compiledして垂加神道(すいか・しんとう)Suika Shintoを興した。

Nonaka Kenzan, a disciple

of Jichu and a chief retainer of the Tosa domain, demonstrated his skill in

reforming the domain's administration, and his disciple Yamazaki Ansai

(1618-1682) taught Neo-Confucianism. At first, he compiled the Shinto theories

of various families and established Suika Shinto.

浅見絅斎(あさみ・けいさい)Asami Keisai

山崎闇斎(やまざき・あんさい)Yamazaki Ansaiの流派schoolを崎門(きもん)kimonといい、佐藤直方(さとう・なおかた)Satō Naokata・浅見絅斎(あさみ・けいさい)Asami Keisai・三宅尚斎(みやけ・しょうさい)Miyake Shosaiらは崎門(きもん)kimonの三傑the three great peopleと称せられた。

The school of Ansai

Yamazaki is called Sakimon, and Naokata Sato, Keisai Asami, and Shosai Miyake

are called Sakimon. He was called one of the three great people.

貝原益軒(かいばら・えきけん)Kaibara Ekiken

『養生訓(ようじょうくん)Yojo-kun』

『女大学(おんな・だいがく)Women's University』

『大和本草(やまと・ほんぞう)Yamato Honzo』

③福岡藩(ふくおかはん)the Fukuoka domainの貝原益軒(かいばら・えきけん)Kaibara Ekikenは『養生訓(ようじょうくん)Yojo-kun』で健康法health methodsを述べ、『和俗童子訓(わぞく・どうじ・くん)Wazoku Doji-kun』の女子教育法the educational methods for girlsを後世の人future

generationsが『女大学(おんな・だいがく)Women's University』として女子の封建道徳feudal morality for womenを説いた。

Ekiken Kaibara of the

Fukuoka domain described health methods in ``Yojo-kun,'' and passed on the

educational methods for girls in ``Wazoku Doji-kun'' to future generations.

``Women's University'' preached feudal morality for women.

また『大和本草(やまと・ほんぞう)Yamato Honzo』は今日なお評価が高い。

Furthermore, ``Yamato

Honzo'' is still highly regarded today.

王陽明(おう・ようめい)Wang Yangming

陽明学(ようめいがく)Yomeigaku

明(みん)the Ming Dynastyの王陽明(おうようめい)Wang Yangmingが創唱した儒学(じゅがく)Confucianismで、「知行合一(ちこう・ごういつ)chikou gouitsu」・「格物致知(かくぶつ・ちち)kakubutsu chichi」を唱えて、実践を重んじたvalued practice。

Confucianism was founded

by Wang Yangming of the Ming Dynasty, who advocated ``chikou gouichi'' and

``kakubutsuchichi,'' and valued practice.

中江藤樹(なかえ・とうじゅ)Nakae Tōju

日本Japanで陽明学(ようめいがく)Yomeigakuを確立establishedしたのは、中江藤樹(なかえ・とうじゅ)Nakae Tōjuである。

It was Toju Nakae who

established Yomeigaku in Japan.

中江藤樹(なかえ・とうじゅ)Nakae Tōjuははじめ朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismを修めたが、形式に流れやすいthe tendency to follow formalismことに不満dissatisfiedを抱いて陽明学(ようめいがく)Yomeigakuに転じ、近江(おうみ)Omi Province(滋賀県Shiga Prefecture)に藤樹書院(とうじゅ・しょいん)Toju Shoinを設けて庶民教化educate the common peopleに努め、近江聖人(おうみ・せいじん)Omi Saintと呼ばれた。

Nakae Toju first studied

Neo-Confucianism, but became dissatisfied with the tendency to follow formalism,

so he turned to Yomeigaku, established Toju Shoin in Omi, worked to educate the

common people, and became a famous Omi Saint. ) was called.

著書に『翁問答(おきな・もんどう)okinamondou』・『鑑草(かがみくさ)kagamigusa』がある。

His works include

``Okina'' and ``Kanso''.

熊沢蕃山(くまざわ・ばんざん)Kumazawa

Banzan(1619~1691)

池田光政(いけだ・みつまさ)Ikeda Mitsumasa(1609~1682)

門人discipleの熊沢蕃山(くまざわ・ばんざん)Kumazawa Banzan(1619~1691)は、岡山藩主the lord of the Okayama domain・池田光政(いけだ・みつまさ)Ikeda Mitsumasaに仕えて、藩政改革reforming

the domain's governmentに手腕をふるったが、『大学或問(だいがく・わくもん)University Wakumon』で参勤交代制の緩和easing the rotation systemや農兵制への復帰returning to an agricultural/military systemなどを説いたことから、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateによって下総(しもうさ)Shimousa Province(千葉県Chiba Prefecture北部)古河(こが)Kogaに禁錮(きんこ)imprisonedされた。

His disciple, Kumazawa

Banzan (1619-1691), served Mitsumasa Ikeda, the lord of the Okayama domain, and

demonstrated his skill in reforming the domain's government, but he was unable

to participate in the ``University Wakumon''. He was imprisoned by the

shogunate in Koga, Shimousa, because he advocated easing the rotation system

and returning to an agricultural/military system.

このような現実を批判criticize realityする革新的な傾向innovative tendencyは、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateから警戒fearedされ、しばしば弾圧suppressedされた。

This innovative tendency

to criticize reality was feared by the shogunate and was often suppressed.

孔子(こうし)Confucius

孟子(もうし)Mencius

古学派(こがくは)Antiquity School

やがて、朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismや陽明学(ようめいがく)Yomeigakuは後世の解釈interpretations of later generationsにすぎず、必ずしも孔子(こうし)Confucius・孟子(もうし)Menciusの教えthe teachingsを正しく伝えるものではないとし、孔孟の思想本来the true nature of Confucius' thoughtを知るためにも、四書(ししょ)the Four Books・五経(ごきょう)the Five Classicsの直接解釈direct interpretationにより聖賢の道the path of the sagesを研究researchすることを主張する古学派(こがくは)が現れた。

Eventually, it was

concluded that Neo-Confucianism and Yomeigaku were merely interpretations of

later generations and did not necessarily convey the teachings of Confucius and

Mencius correctly, and in order to understand the true nature of Confucius'

thought, it was necessary to follow the path of the sages through direct

interpretation of the Four Books and Five Classics. A school of antiquity

emerged that advocated research.

山鹿素行(やまが・そこう)Yamaga Sokō(1622~1685)

林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razan(1583~1657)に学んだが『聖教要録(せいきょう・ようろく)Seikyo Yoroku』を著して朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismを批判し、日本独自の儒学思想a uniquely Japanese form of Confucian thoughtとして古学(こがく)ancient studiesの先駆pioneerとされた。

He studied under Hayashi

Razan (1583-1657), but he wrote ``Seikyo Yoroki,'' which criticized

Neo-Confucianism, and became a pioneer of ancient studies as a uniquely

Japanese form of Confucian thought.

現実の生活に役立つ学問learning

that would be useful in real lifeを求め、聖人(孔孟)の学the study of saints (Kong Meng)=聖学sacred studiesの重要性the importanceを説いた。

He sought learning that

would be useful in real life, and preached the importance of the study of

saints (Kong Meng), or sacred studies.

保科正之(ほしな・まさゆき)Hoshina

Masayuki(1611~1672)

保科正之(ほしな・まさゆき)Hoshina

Masayuki(1611~1672)らは、これを幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの教学(きょうがく)the teachingsを批判criticismしたものとして、山鹿素行(やまが・そこう)Yamaga Sokō(1622~1685)を赤穂(あこう)Akoに流した。

Masayuki Hoshina

(1611-1672) and others considered this to be a criticism of the teachings of

the shogunate, and sent Yamaga Souyuki (1622-1685) to Ako.

この間に山鹿素行(やまが・そこう)Yamaga Sokōは『中朝事実(ちゅうちょう・じじつ)Chucho Jijitsu』で、儒者Confucian scholarsがいたずらに中国Chinaを中華Chinaと尊ぶhonoringのに反対opposedし、日本Japanが中朝Chucho・中華Chinaであると主張した。

During this period,

Souyuki Yamaga wrote "Chucho Jijitsu" in which he opposed Confucian

scholars' needlessly honoring China as China, and claimed that Japan was China,

Korea, and China. did.

山鹿素行(やまが・そこう)Yamaga Sokōは兵学者military

scholarでもあり、山鹿流兵学the Yamaga school of military tacticsを完成し、また『武家事記(ぶけ・じき)Buke-jiki』で武家の歴史the history of the samurai familyに基づき武士道理論the

theory of Bushidoを大成した。

Yamaga Souyuki (Yamaga

Souyuki) was also a military scholar who perfected the Yamaga school of

military tactics, and also perfected the theory of Bushido based on the history

of the samurai family in ``Buke-jiki.''

伊藤仁斎(いとう・じんさい)Itō Jinsai(1627~1705)

堀川学派(ほりかわがくは)the Horikawa

school

京都(きょうと)Kyotoの伊藤仁斎(いとう・じんさい)Itō Jinsai(1627~1705)は朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismには仏教Buddhism・道家(どうか)Daoism(諸子百家the 100 schools of thoughtの一つ)の思想の混入the incorporationを見咎め、厳しい文献批判のうえ学問の根拠を示した『論語古義(ろんご・こぎ)Analects Kogi』・『孟子古義(もうし・こぎ)Mencius Kogi』を著し、古義学派(こぎ・がくは)the Kogi school・堀川学派(ほりかわ・がくは)the Horikawa schoolと称した。

Jinsai Ito (1627-1705) of

Kyoto criticized the incorporation of Buddhism and Daoism (one of the 100

schools of thought) into Neo-Confucianism, and based on harsh literary

criticism, he established the basis for the study. He wrote the ``Analects of

the Analects'' and ``Mencius of Mencius'' and called them the Kogi school and

the Horikawa school.

京都(きょうと)Kyoto堀川(ほりかわ)Horikawaの私塾private school古義堂(こぎどう)Kogidoの門人studentsは町人を含め3000余人、富商・公家との交流も深かった。

Kogido, a private school

in Horikawa, Kyoto, had over 3,000 students, including townspeople, and had

close ties with wealthy merchants and court nobles.

思想を概説outlines his

thoughtsした『童子問(どうじもん)Dojimon』は有名。

``Dojimon'', which

outlines his thoughts, is famous.

石田梅岩(いしだ・ばいがん)Ishida Baigan(1685~1744)

荻生徂徠(おぎゅう・そらい)Ogyū Sorai・石田梅岩(いしだ・ばいがん)Ishida Baiganに影響を与えた。

He influenced Sorai Ogyu

and Baigan Ishida.

伊藤東涯(いとう・とうがい)Itō Tōgai

この学派は、その子伊藤東涯(いとう・とうがい)Itō Tōgaiによって継承・大成された。

This school was inherited

and developed by his son Togai Ito.

荻生徂徠(おぎゅう・そらい)Ogyū Sorai(1666~1728)

蘐園学派(けんえん・がくは)the Kenen

school

17世紀末At the end of the 17th centuryに、江戸Edoに荻生徂徠(おぎゅう・そらい)Ogyū Sorai(1666~1728)が、朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismを離れて独自の古学(こがく)ancient studiesの体系を作り上げた。

At the end of the 17th

century, in Edo, Ogyu Sorai (1666-1728) broke away from Neo-Confucianism and

created his own system of ancient studies.

主著『弁道(べんどう)Bendo』・『弁名(べんめい)Benmei』によると、政治の狙いthe aim of politicsは社会の制度the social systemであって、個人の道徳personal moralityを修めることにはないとして、政治politicsを道徳moralityから切り離し、経世の学(けいせい・の・がく)the science of the secular worldを樹立しようとした。

According to his main works, Bendo and Benmei, he believed that the aim of politics was the social system, not the cultivation of personal morality, and tried to separate politics from morality and establish the science of the secular world.

徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimune(在職1716年~1745年)

8代将軍the 8th shogun

『六諭衍義大意(りくゆえんぎ・たいい)Rikuengitaii』

将軍the shogun・徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimuneの命で清(しん)the Qing Dynastyの『六諭衍義(りくゆえんぎ)Rikuengi』に訓点を施して呈上し、また徳川吉宗(とくがわ・よしむね)Tokugawa Yoshimuneの諮問に答えた『政談(せいだん)Seidan』で、武家窮乏the poverty of samurai familiesは武家samurai familiesが一生旅宿住いliving in innsの状態にあることから生じたとして、貨幣経済monetary economyの発達を抑え、武士の帰農having samurai return to farmingによる幕藩体制維持maintaining

the shogunate systemを説いた。

At the behest of the

shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune, he gave a commentary on the Qing Dynasty's Rikuyurengi

and presented it, and in response to Tokugawa Yoshimune's advice, Seidan. He

argued that the poverty of samurai families was caused by samurai families

living in inns all their lives, and advocated suppressing the development of a

monetary economy and maintaining the shogunate system by having samurai return

to farming.

本居宣長(もとおり・のりなが)Motoori

Norinaga

私塾private

school・蘐園(けんえん)Kenenから蘐園学派(けんえん・がくは)the Kenen schoolとも、学問の考証学的方法archaeological method of studyから古文辞学派(こぶんじ・がくは)the Kobunji schoolとも呼ばれ、国学者the Japanese scholar・本居宣長(もとおり・のりなが)Motoori Norinagaに影響を与えた。

It is also known as the

Kenen school, a private school, and the Kozono school because of its

archaeological method of study, and it influenced the Japanese scholar Norinaga

Motoori.

荻生徂徠(おぎゅう・そらい)Ogyū Soraiは、朱子学(しゅしがく)Neo-Confucianismの道学的側面the moralistic aspectsをも批判し、人間の自然な心情を尊重し、文芸作品を純粋に文芸として味わうことを勧め、道学的解釈moralistic

interpretationsを排した。

Ogyu Sorai also

criticized the moralistic aspects of Neo-Confucianism, recommended respecting

the natural feelings of humans, and enjoying literary works purely as literary

arts, and rejected moralistic interpretations.

太宰春台(だざい・しゅんだい)Dazai Shundai(1680~1747)

服部南郭(はっとり・なんかく)Hattori

Nankaku

荻生徂徠(おぎゅう・そらい)Ogyū Soraiの門下discipleから、『経済録(けいざいろく)Keizairoku』や『産語(さんご)Sango』を著した太宰春台(だざい・しゅんだい)Dazai Shundai(1680~1747)、詩文poetryに優れた山県周南(やまがた・しゅうなん)Yamagata Shunan、古文辞研究(こぶんじ・けんきゅう)the study of ancient Japanese dictionaryに活躍した服部南郭(はっとり・なんかく)Hattori Nankakuなどが出た。

Dazai Shundai

(1680-1747), a disciple of Ogyu Sorai, who wrote Keiroku and Sango, and

Yamagata Shunan, who was excellent in poetry. Among them were Hattori Nankaku,

who was active in the study of ancient Japanese dictionary.

太宰春台(だざい・しゅんだい)Dazai Shundaiは『経済録(けいざいろく)Economic Records』のなかで、重農主義Physiocratism的立場に立ちながらも武士の商業活動the commercial activities of samuraiと藩専売Domain

monopolyなどを説いた。

In his Economic Records,

Dazai Shundai advocated the commercial activities of samurai and clan monopoly,

while taking a position of Physiocratism.

徳川家光(とくがわ・いえみつ)Tokugawa Iemitsu(在職1623~1651)

3代将軍the 3rd shogun

史学の発達Development

of History

儒学(じゅがく)Confucianismの発展に伴って、歴史(れきし)Historyに対する関心が高まった。

With the development of

Confucianism, interest in history increased.

3代将軍the 3rd shogun・徳川家光(とくがわ・いえみつ)Tokugawa Iemitsu(在職1623~1651)の命によって林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razan(1583~1657)は『本朝編年録(ほんちょう・へんねんろく)Honcho Henenroku』を編纂compiledした。

Hayashi Razan (1583-1657)

compiled the ``Honcho Henroku'' by order of the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu

(1623-1651).

その子son・林鵞峯(はやし・がほう)Hayashi Gahō(春斎(しゅんさい)Shunsai)(1618~1680)が引き継ぎ、1670年(寛文10年)、編年体(へんねんたい)the chronological versionの『本朝通鑑(ほんちょう・つがん)Honcho Tsugan』が完成completedした。

His son Gahou Hayashi

(1618-1680) took over the work, and in 1670 (10th year of Kanbun), completed

the chronological version of the Honcho Tsukan.

徳川光圀(とくがわ・みつくに)Tokugawa

Mitsukuni(1628~1700)

水戸藩(みとはん)Mito Domain(茨城県(いばらきけん)Ibaraki Prefecture)藩主(はんしゅ)the Lord of the Domain徳川光圀(とくがわ・みつくに)Tokugawa Mitsukuni(1628~1700)は1657年(明暦3年)江戸Edoに史局historical bureauを設け、全国から学者scholarsを集めて『大日本史(だいにほんし)the Great History of Japan』の編纂に着手した。

In 1657 (Meireki 3), the feudal lord Tokugawa Mitsukuni (1628-1700) established a historical bureau in Edo, gathered scholars from all over the country, and began compiling the Great History of Japan.

彰考館(しょうこうかん)Shokokan

1672年(寛文12年)に史局historical bureauを小石川(こいしかわ)Koishikawa藩邸(はんてい)the domain's residenceに移し、彰考館(しょうこうかん)Shokokanと称して編纂を継続した。

In 1672 (Kanbun 12), the

history bureau was moved to the Koishikawa domain residence, where it continued

to compile under the name Shokokan.

この事業を通じて大義名分論(たいぎ・めいぶん・ろん)the theory of just causeに基づく水戸学(みとがく)Mito-gakuが発達し、幕末the end of the Edo periodの尊王論(そんのうろん)the theory of reverence for the kingに思想的根拠ideological

basisを与えた。

Through this project,

Mito-gaku (Mito-gaku), which was based on the theory of just cause, developed

and provided the ideological basis for the theory of reverence for the king at

the end of the Edo period.

新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakuseki(1657年~1725年)

新井白石(あらい・はくせき)Arai Hakuseki(1657~1725)は、儒学的合理主義Confucian rationalismに基づいて、批判的・実証的な方法critical and empirical methodによる史書historical worksを著し、近世史学early modern historiography上に貢献した。

Arai Hakuseki (1657-1725)

contributed to early modern historiography by writing historical works using a

critical and empirical method based on Confucian rationalism.

徳川家宣(とくがわ・いえのぶ)Tokugawa Ienobu(在職1709~1712)

徳川綱豊(とくがわ・つなとよ)Tsunatoyo

6代将軍the 6th shogun

徳川綱吉(とくがわつなよし)Tokugawa

Tsunayoshiの甥nephew

『読史余論(とくしよろん)Tokushi Yoron』は6代将軍the 6th shogun徳川家宣(とくがわ・いえのぶ)Tokugawa Ienobu(在職1709~1712)に進講した稿案で、儒学的合理主義Confucian rationalismにたつ科学的方法scientific methodを示している。

``Tokushi Yoron'' is a draft

presented to the sixth Shogun Tokugawa Ienobu (1709-1712), and it presents a

scientific method that is consistent with Confucian rationalism.

また大名(だいみょう)feudal

lordsの系譜や事蹟を考証examines the genealogy and historyし、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateとの関係を明らかにした『藩翰譜(はんかんふ)Hankanfu』、『日本書紀(にほんしょき)Nihon Shoki(The Chronicles of Japan)』神代巻the Kamiyo volumeに科学的合理的解釈scientific and rational interpretationを加えた『古史通(こしつう)Koshitsū』などがある。

In addition,

``Hankanfu,'' which examines the genealogy and history of feudal lords and

clarifies their relationship with the shogunate, and ``Koshitsu,'' which adds a

scientific and rational interpretation to the Jindai volume of ``Nihon Shoki.''

etc.).

そのほか、実証的研究の結果result of empirical researchとして語源辞書the etymology dictionaryの『東雅(とうが)Toga』がある。

Another result of

empirical research is the etymology dictionary ``Toga.''

本居宣長(もとおり・のりなが)Motoori

Norinaga(1730~1801)

国学の萌芽(こくがく・の・ほうが)

The Germ of Japanese Studies

自然科学the natural

sciencesの発展は次第に合理主義精神rationalist spiritを育て、これを背景に、古典を対象とする学問studies that focused on the classicsでも、中世和学medieval

Japanese studiesの秘事口伝the esoteric oral traditionや格式formalityを排除し、儒教・仏教の道徳的な見解the moral views of Confucianism and Buddhismにとらわれない立場で研究を行おうとする傾向A tendency to conduct researchが現れた。

The development of the

natural sciences gradually fostered a rationalist spirit, and against this

background, even in studies that focused on the classics, the esoteric oral

tradition and formality of medieval Japanese studies were eliminated, and from

a standpoint that was not bound by the moral views of Confucianism and

Buddhism. A tendency to conduct research has emerged.

北村季吟(きたむら・きぎん)Kitamura

Kigin(1624~1705)

国学(こくがく)Kokugaku(Japanese Studies)の芽生えbeginningsは、和歌(わか)Waka(Japanese poem)における古今伝授(こきん・でんじゅ)Kokin Denjuを批判し、歌詞の自由the freedom of lyrics・歌風の自然簡素the natural simplicity of styleを主唱するという歌学(かがく)poetryの革新運動revolutionary movementの形をとって出発した。

The beginnings of

Kokugaku began in the form of a revolutionary movement in poetry that

criticized the ancient and modern teachings of waka and advocated the freedom

of lyrics and the natural simplicity of style.

戸田茂睡(とだ・もすい)Toda Mosui

近江(おうみ)Omi Province(滋賀県Shiga

Prefecture)の北村季吟(きたむら・きぎん)Kitamura Kigin(1624~1705)は『源氏物語湖月抄(げんじものがたり・こげつしょう)The Tale of Genji Kogetsusho』・『枕草子春曙抄(まくらのそうし・しゅんしょしょう)The Pillow Book Shunshosho』を著して古典研究classical researchを行い、江戸Edoの戸田茂睡(とだ・もすい)Toda Mosuiは、伝統traditionと因習conventionに束縛boundされて定型化formalizedした二条家(にじょうけ)the Nijo familyの歌学(かがく)の方法formalized

poetic methods(制の詞formal lyricsなど)を否定rejectedし、歌詞の自由lyrical freedomと自然簡単natural simplicityな新風new styleを唱えた。

Kigin Kitamura

(1624-1705) of Omi conducted classical research by writing ``The Tale of Genji

Kogetsusho'' and ``The Pillow Book Shunshosho'', and also Sui) rejected the

Nijo family's formalized poetic methods (such as formal lyrics), which were

bound by tradition and convention, and advocated a new style of lyrical freedom

and natural simplicity.

Toda Mosui of the Edo

period rejected the Nijo family's formalized poetic methods (such as formal

lyrics) that were bound by tradition and convention, and instead embraced the

freedom of lyrics and a natural, simple new style. chanted.

著書に『梨本集(なしのもと・しゅう)Nashinomoto Collection』がある。

His works include

``Nashimoto Collection''.

下河辺長流(しもこうべ・ながる)Shimokobe Nagaru(1627?~1686)

契沖(けいちゅう)Keichū(1640~1701)

大坂Osakaの下河辺長流(しもこうべ・ながる)Shimokobe Nagaru(1627?~1686)は、独創的な見解に基づき『万葉集(まんようしゅう)Manyoshu』など古典研究classical researchを行い、僧monk契沖(けいちゅう)Keichū(1640~1701)は、下河辺長流(しもこうべ・ながる)Shimokobe Nagaruの後を継いで水戸藩(みとはん)Mito Domainの徳川光圀(とくがわ・みつくに)Tokugawa Mitsukuniの委嘱保護the commission and protectionのもとで『万葉代匠記(まんよう・だいしょうき)Manyodaishoki』を著し、従来の堂上歌学(どうじょう・かがく)the temple's poeticsの誤りを批判し、儒・仏による解釈the Confucian and Buddhist interpretationsを排して古典・古歌(こか)classical and ancient poemsの注釈the annotations・仮名づかいkana usageの研究the studyに新しい見解を示した。

Shimokobe Nagaru

(1627?-1686) of Osaka conducted classical research such as the Manyoshu based

on his original views, and Soki Keichu (1640-1701) Successor to Shimokobe

Nagaru, he wrote ``Manyodaishoki'' under the commission and protection of

Tokugawa Mitsukuni of the Mito domain, He criticized the errors in the temple's

poetics, rejected the Confucian and Buddhist interpretations, and presented a

new perspective on the study of the annotations and kana usage of classical and

ancient poems.

それは先人の説the theories of his predecessorsにとらわれない自由な態度free

attitudeと、実証的な文献学的方法empirical philological methodsによって、国学(こくがく)の祖the

father of Japanese studiesと呼ばれるにふさわしい、国学勃興the rise of Japanese studiesの先駆的な役割pioneering roleを果たした。

With his free attitude,

unfettered by the theories of his predecessors, and his empirical philological

methods, he was worthy of being called the father of Japanese studies, and

played a pioneering role in the rise of Japanese studies.

本草学(ほんぞう・がく)Herbalism

自然科学(しぜん・かがく)Natural

science

鎖国(さこく)national isolationの結果、自然科学(しぜん・かがく)Natural scienceなどの西洋文化の導入the introduction of Western cultureは制約を受けた。

As a result of national

isolation, the introduction of Western culture such as natural science was

restricted.

しかし17世紀後半the latter half of the 17th century、産業・経済の発展the development of industry and the economyに伴い、実証的・合理的な精神empirical and rational mindが育てられ、農学(のうがく)Agricultural science・本草学(ほんぞうがく)Herbalism・暦学(れきがく)Calendar・医学(いがく)Medicine・数学(すうがく)Mathematicsなど実用の学問(実学(じつがく)practical studies)が次第に発達した。

However, in the latter

half of the 17th century, with the development of industry and the economy, an

empirical and rational mind was cultivated, and practical studies such as

agriculture, herbalism, calendar science, medicine, and mathematics gradually

developed.

宮崎安貞(みやざき・やすさだ)Miyazaki

Yasusada(1623~1697)

『農業全書(のうぎょう・ぜんしょ)Nougyo Zensho』

江戸時代the Edo

periodには、農業技術agricultural technologyの向上をはかるため、農学(のうがく)Agricultural scienceが発達した。

During the Edo period,

agricultural science was developed to improve agricultural technology.

宮崎安貞(みやざき・やすさだ)Miyazaki

Yasusada(1623~1697)は最初の体系的農書systematic agricultural bookである『農業全書(のうぎょう・ぜんしょ)Nougyo Zensho』を著し、農業技術の進歩the advancement of agricultural technologyに貢献した。

Yassada Miyazaki

(1623-1697) wrote the first systematic agricultural book, Nougyo Zensho, and

contributed to the advancement of agricultural technology.

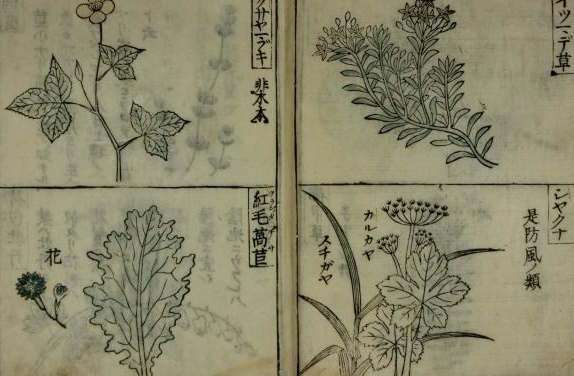

『本草綱目(ほんぞう・こうもく)Compendium of Materia Medica』

李時珍(り・じちん)Li Shizhen

本草学(ほんぞうがく)Herbalismは、中国Chinaに起こった薬用動植鉱物medicinal plants, animals, and mineralsを研究する学問he studyで、1607年(慶長12年)に林羅山(はやし・らざん)Hayashi Razanが長崎(ながさき)Nagasakiから明(みん)the Ming dynastyの『本草綱目(ほんぞう・こうもく)Compendium of Materia Medica』(李時珍(り・じちん)Li Shizhen)を携えて帰り、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateに献上してその基礎が置かれた。

Herbalism is the study of

medicinal plants, animals, and minerals that originated in China. He returned

with a copy of ``Ku'' (Li Shizhen) and presented it to the shogunate, where its

foundation was laid.

貝原益軒(かいばら・えきけん)Kaibara Ekiken

『大和本草(やまと・ほんぞう)Yamato Honzo』

18世紀 the 18th centuryに入り、儒者Confucian

scholarの貝原益軒(かいばらえきけん)Kaibara Ekikenは『大和本草(やまとほんぞう)Yamato Honzo』を著し、わが国Japaneseにおける本草学(ほんぞうがく)Herbalismを実証的empiricalな博物学(はくぶつがく)Natural historyの域realmに近づけた。

In the 18th century, the

Confucian scholar Kaibara Ekiken wrote ``Yamato Honzo,'' bringing Japanese

herbal studies closer to the realm of empirical natural history.

稲生若水(いのう・じゃくすい)Inō Jakusui(1655~1715)

前田綱紀(まえだ・つなのり)Maeda

Tsunanori

『庶物類纂(しょぶつ・るいさん)Shobutsu ruisan(common

goods collection)』

加賀藩(かがはん)Kaga Domain(石川県Ishikawa

Prefecture)の侍医(じい)court physician稲生若水(いのう・じゃくすい)Inō Jakusui(1655~1715)は、藩主(はんしゅ)the Lord of the Domain・前田綱紀(まえだ・つなのり)Maeda Tsunanoriの命を受けて『庶物類纂(しょぶつ・るいさん)Shobutsu ruisan(common

goods collection)』を編纂して、物産学(ぶっさんがく)Bussan-gaku・博物学(はくぶつがく)Natural historyへの発展や分化を示した。

Inou Jakusui (1655-1715),

a samurai physician of the Kaga domain, compiled the "Shobutsuruisan"

(common goods collection) at the behest of the feudal lord, Maeda Tsunanori. It

showed the development and differentiation into science and natural history.

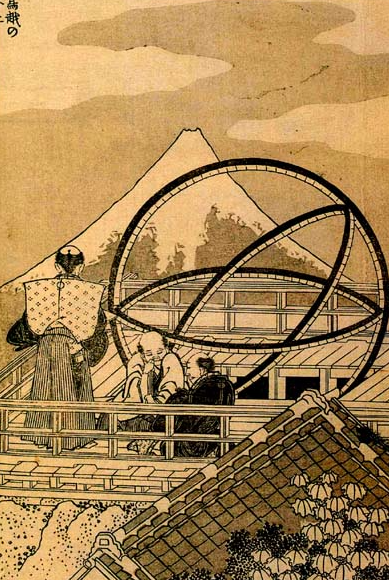

安井算哲(やすい・さんてつ)Yasui

Santetsu(渋川春海(しぶかわ・はるみ)Shibukawa Harumi)

安井算哲(やすい・さんてつ)Yasui

Santetsu(渋川春海(しぶかわ・はるみ))Shibukawa Harumi(1639~1715)は、元(げん)the Yuan dynastyの「授時暦(じゅじれき)Juji Calendar」をもとに精密な天文観測と計算precise astronomical observations and calculationsの結果、日本人the

first Japanese personとして最初の画期的な暦(れき)Calendarを編成し、貞享暦(じょうきょう・れき)Jokyo Calendarと呼ばれた。

Santetsu Yasui (Harumi

Shibukawa) (1639-1715) was the first Japanese person to create the He compiled

a revolutionary calendar, which was called the Jokyo Calendar.

As a result of precise

astronomical observations and calculations based on the Yuan dynasty's ``Juji

Calendar'', the first epoch-making calendar for Japanese people was compiled,

and the Jokyo Calendar was created. It was called.

862年(貞観4年)以来823年間長く用いられてきた中国Chinese

calendarの「宣明暦(せんみょう・れき)Xuanming calendar」に代わって、1684年(貞享1年)改暦(かいれき)Calendar reform宣下(せんげ)imperial proclamationがあり、翌1685年(貞享2年)から採用された。

In 1684 (1st year of

Jokyo), the Chinese calendar was revised to replace the ``Senmyoreki'' that had

been in use for 823 years since 862 (4th year of Jogan), and in 1685 (2nd year

of Jokyo) the following year. It was adopted from 2010).

天文方(てんもん・かた)Astronomical Department

幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateは新たに天文方(てんもん・かた)Astronomical Departmentを設け、安井算哲(やすい・さんてつ)Yasui Santetsuを招いて天文(てんもん)astronomy・暦法(れきほう)calendaringに携わらせた。

The shogunate established

a new Astronomical Department and invited Santetsu Yasui to work on astronomy

and calendaring.

算盤(そろばん)abacus

算盤(そろばん)abacus

城郭建築castle

construction・灌漑治水irrigation and flood control・検地land surveyingなどの土木工事civil engineering worksに必要な測量・計算surveying and calculationsや、商品経済commodity economyの発展に伴う商取り引き上の計算calculations for commercial transactionsの必要から、実学(じつがく)practical studiesとしての和算(わさん)Japanese mathematicsが発達を遂げた。

Wasan developed as a

practical science due to the need for surveying and calculations needed for

civil engineering works such as castle construction, irrigation and flood

control, and land surveying, as well as calculations for commercial

transactions with the development of the commodity economy.

日常の計算器として、中国Chinaから算盤(そろばん)abacusが輸入importedされて改良が加えられ、ひろく普及した。

The abacus was imported

from China, improved upon, and became widely used as an everyday calculator.

毛利重能(もうり・しげよし)Mōri Shigeyoshi

吉田光由(よしだ・みつよし)Yoshida

Mitsuyoshi(1598~1672)

『塵劫記(じんこうき)Jinkōki』

毛利重能(もうり・しげよし)Mōri Shigeyoshiは、1622年(元和8年)に『割算書(わりさんしょ)Warisansho』を著し、吉田光由(よしだ・みつよし)Yoshida Mitsuyoshi(1598~1672)は、1627年(寛永4年)に珠算(しゅざん)Chinese Zhusuanを中心とする『塵劫記(じんこうき)Jinkōki』を著し、実用数学practical mathematicsの入門書introductory bookとして活用された。

Shigeyoshi Mouri wrote

"Warisansho" in 1622, and Mitsuyoshi Yoshida (1598-1672) wrote the

book "Warisansho" in 1627. In the 4th year of Kanei (Kanei 4), he

wrote ``Jingoki,'' which mainly focuses on abacus, and it was used as an

introductory book on practical mathematics.

関孝和(せき・たかかず)Seki Takakazu(1640頃~1708)

元禄the Genroku

periodの頃、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの勘定吟味役(かんじょう・ぎんみやく)the chief account inspector関孝和(せき・たかかず)Seki Takakazu(1640頃~1708)は、筆算(ひっさん)式の演段術(えんだんじゅつ)using the written method of algebra(代数学(だいすうがく)Algebra)を始め、円理法(えんりほう)Enri methodを案出した。

Around the Genroku period,

the shogunate's accounting examiner, Takakazu Seki (c. 1640-1708), began using

the written method of algebra and devised the Enri method.

『発微算法(はつびざんぽう)Hatsubizanpou』

著書『発微算法(はつびざんぽう)Hatsubizanpou』(1674年刊行)は、円周率(えんしゅうりつ)Pi・円の面積the area of a circleから微積分(びせきぶん)Calculusを述べ、わが国における高等数学higher mathematicsの発展に画期を与えた。

His book

``Hatsubizanpou'' (published in 1674) described calculus based on pi and the

area of a circle, and marked a turning point in the development of higher

mathematics in Japan.

建部賢弘(たけべ・かたひろ)Takebe

Katahiro

関流The Seki

Schoolは門弟disciple建部賢弘(たけべ・かたひろ)Takebe

Katahiroに引き継がれ、和算(わさん)Japanese mathematicsの主流を形成したが、やがて秘伝化secret traditionした。

The Seki School was

inherited by his disciple Katahiro Takebe and formed the mainstream of Wasan,

but eventually became a secret tradition.

曲直瀬道三(まなせ・どうさん)Manase Dōsan(1507~1594)

江戸初期the early Edo

periodまでは、中国Chinaの元(げん)the Yuan dynasty・明(みん)the Ming dynastyの医術medical techniquesが中心で、曲直瀬道三(まなせ・どうさん)Manase Dōsan(1507~1594)の李朱医学(りしゅ・いがく)(李東垣(り・とうえん)Li Dongkei・朱丹溪(しゅ・たんけい)Zhu Dankeらの医学medicine)系統が栄えた。

Until the early Edo

period, China's Yuan and Ming dynasty medical techniques were the main focus,

and the Li Zhu medicine system of Dosan Manase (1507-1594) (medicine of Li

Dongkei, Zhu Danke, etc.) flourished.

名古屋玄医(なごや・げんい)Nagoya Gen'i

しかし、京都(きょうと)Kyotoの名古屋玄医(なごや・げんい)Nagoya Gen'iは漢代の医方the medical methods of the Han Dynastyへの復古restorationを唱え、実証的精神empirical

spiritを重んじ古医方(こいほう)school of ancient medicineの一派を形成した。

However, Nagoya Gen'i of

Kyoto advocated a restoration of the medical methods of the Han Dynasty, and

formed a school of ancient medicine that valued the empirical spirit.

後藤艮山(ごとう・こんざん)Goto Konzan

古医方(こいほう)Koihoは、17世紀後半に「一気留滞論(いっき・りゅうたいろん)Ikkiryutairon」を唱えた後藤艮山(ごとう・こんざん)Goto Konzanによって完成された。

Koiho was completed in

the late 17th century by Konzan Goto, who advocated the theory of ``all-at-once

residence.''

吉益東洞(よします・とうどう)Yoshimasu

Tōdō

吉益東洞(よします・とうどう)Yoshimasu

Tōdōも「万病一毒説(まんびょう・いちどくせつ)`all-illness-all-poison theory」を唱えて、臨床的な実験医学clinical experimental medicineによる実証的精神empirical spiritを主張した。

Yoshimasu Todo also

advocated the ``all-illness-all-poison theory'' and advocated an empirical

spirit based on clinical experimental medicine.

山脇東洋(やまわき・とうよう)Yamawaki Tōyō(1705~1762)

『蔵志(ぞうし)Zoshi』

後藤艮山(ごとう・こんざん)Goto Konzanに学んだ山脇東洋(やまわき・とうよう)Yamawaki Tōyō(1705~1762)は、1754年(宝暦4年)に死刑囚の死体解剖dissected the corpses of death row inmatesを行い、日本最初の解剖図録Japan's first anatomical catalog『蔵志(ぞうし)Zoshi』を著して旧説の誤りthe errors of the old theoryを正した。

Yamawaki Toyo (1705-1762),

who studied under Goto Konzan, dissected the corpses of death row inmates in

1754 (Horeki 4) and published Japan's first anatomical catalog, Kura. He

corrected the errors of the old theory by writing Zoshi.

西玄甫(にし・げんぽ)Nishi Genpo

いっぽう、西洋医学Western medicineは外科の分野the field of surgeryで行われ、元禄the Genroku eraの頃、長崎(ながさき)Nagasakiの通詞(つうじ)(通訳)interpreterである西玄甫(にし・げんぽ)Nishi Genpoは幕府医官medical officer of the shogunateとして迎えられた。

On the other hand,

Western medicine was practiced in the field of surgery, and during the Genroku

era, Nishi Genpo, a Nagasaki interpreter, was appointed as a medical officer of

the shogunate.

本木良意(もとき・りょうい)Motoki Ryoi

また、同じく通詞(つうじ)interpreterの本木良意(もとき・りょうい)Motoki Ryoiはオランダ解剖図Dutch anatomical chartsの翻訳translatedを行って、以後の蘭学発展development of Dutch studiesの基礎を築いた。

In addition, Ryoi Motoki,

also an interpreter, translated Dutch anatomical charts and laid the foundation

for the subsequent development of Dutch studies.

檀家制度(だんか・せいど)Danka system(寺請制度(てらうけ・せいど)Terauke system)

仏教と神道Buddhism and

Shinto

寺院Templesは諸宗寺院法度(しょしゅう・じいん・はっと)the temple law of various sectsで幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの統制下under the controlに置かれ、寺請制度(てらうけ・せいど)Terauke systemによって幕府支配の末端機構terminal institution under the shogunate's controlとなり、種々の保護various

protectionsを加えられたが、宗教religionとしては停滞stagnatedした。

Temples were placed under

the control of the shogunate under the temple law of various sects, and through

the temple petition system they became a terminal institution under the

shogunate's control, and although they were given various protections, they stagnated

as a religion.

隠元隆琦(いんげん・りゅうき)Ingen Ryūki(1592~1673)

萬福寺(まんぷくじ)Manpuku-ji 宇治(うじ)Uji 黄檗山(おうばくさん)Mt. Ōbaku

新宗派の成立Establishment

of a New sect

わずかに、1654年(承応3年)に来日した明(みん)the Ming dynastyの僧monk隠元隆琦(いんげん・りゅうき)Ingen Ryūki(1592~1673)が、禅宗(ぜんしゅう)Zen Buddhismの一派sect黄檗宗(おうばくしゅう)Ōbaku-shūを開いたことが注目される。

It is noteworthy that the

Ming dynasty monk Ingen Ryuki (1592-1673), who came to Japan in 1654, founded

the Obaku sect, a sect of Zen Buddhism.

隠元隆琦(いんげん・りゅうき)Ingen Ryūkiは宇治(うじ)Ujiに寺地temple landを与えられ、黄檗山(おうばくさん)Mt. Ōbaku万福寺(まんぷくじ)Manpuku-jiを創建foundedした。

Ingen was given temple

land in Uji and founded Mt. Obaku Manpuku-ji Temple.

吉川惟足(よしかわ・これたり)Yoshikawa

Koretari

吉田兼倶(よしだ・かねとも)Yoshida

Kanetomo(1435~1511)

吉田神道(よしだ・しんとう)Yoshida

Shinto

神道(しんとう)Shinto

あまりふるわなかったが、仏教(ぶっきょう)Buddhismとの関係を脱して儒教(じゅきょう)Confucianismと結びつき、新しい展開が見られた。

Although it did not do

much, new developments were seen as it moved away from its relationship with

Buddhism and linked it with Confucianism.

17世紀後半the latter half of the 17th centuryには、幕府(ばくふ)the shogunateの神道方(しんとう・かた)the Shinto officialになった吉川惟足(よしかわ・これたり)Yoshikawa Koretariが、吉田神道(よしだ・しんとう)Yoshida Shintō(唯一神道(ゆいいつ・しんとう)Yuiitsu Shintō)に儒学Confucianismを加味した吉川神道(よしかわ・しんとう)Yoshikawa Shintoをおこし、また伊勢神宮(いせ・じんぐう)Ise Jingu Shrineの神官priest度会延佳(わたらい・のぶよし)は、伊勢神道(いせ・しんとう)Ise Shintoを儒教思想Confucianism中心のものに大成した。

In the latter half of the

17th century, Yoshikawa Koretari, who became the Shinto official of the

shogunate, created Yoshikawa Shinto, which added Confucianism to Yoshida Shinto

(the only Shinto). Nobuyoshi Watara, a priest at Ise Jingu Shrine, also

developed Ise Shinto into one centered on Confucianism.

山崎闇斎(やまざき・あんさい)Yamazaki Ansai(1618~1682)

吉川惟足(よしかわ・これたり)Yoshikawa

Koretariに学んだ朱子学者Neo-Confucian scholar山崎闇斎(やまざき・あんさい)Yamazaki Ansaiは、儒学Confucianismと諸家の神道説the Shinto theories of various schoolsとを集大成integratingして垂加神道(すいか・しんとう)Suika Shintoを唱えた。

Ansai Yamazaki, a

Neo-Confucian scholar who studied under Koretari Yoshikawa, advocated Suika

Shinto by integrating Confucianism and the Shinto theories of various schools.